This is Part One of a five-part series on creative African artists

Continue to Parts: 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5

Crouched in a corner of a cavernous, dark basement at the bottom of a building, a tall man in a long gray overcoat watches three visitors to his “installation” struggle to navigate their way through his creation -- a labyrinth of scores of wooden beams, angular and painted black, some crisscrossed and suspended above the floor, others reaching to the roof.

The artist remains unseen by his audience. He’s on the fringes, on the margins, invisible, as he so often has been in his life so far. His eyes narrow and squint in the nebulous haze, straining to see the people who are viewing -- and experiencing -- his work.

They duck their heads and lift their legs over the sharp pieces of wood, trying to avoid injury. In the middle of the installation, they pause, unsure of how to proceed, before reversing. None smiles, or talks. There’s disquiet in the dank air. The streams of red rust from decaying metal pipes that run down the room’s unpainted concrete walls add to the atmosphere of oppression. Sound is muffled, as if in a vacuum.

With intense interest, Serge Alain Nitegeka watches his “participators” – as he prefers to call them – labor their way to an exit, an escape, from the maze and its industrial coldness and potential to inflict pain. They often stumble. They often appear confused.

“This isn’t something just to look at,” Nitegeka told VOA. “I want people to become involved, to feel something when they are inside my installation. The body has to be shifted. It’s about the viewer becoming a participator, the sculpture or the installation being completed by someone interacting with it.”

Thus, he maintained his audiences are the “co-creators” of his latest work, entitled “…and walk in my shoes….” He explained: “Me being the author, me being the artist who put it up – I’m kind of prompting the viewer to walk in my shoes, as it were.”

The shoes that Nitegeka (28) is referring to are certainly not comfortable.

‘Discord and dislocation’

In 1993, when Nitegeka was 11, civil war broke out in his native Burundi. “Then my process of migration – forced migration – began taking place,” he remembered. He left his homeland with his family for neighboring Rwanda. But just a few months later, that country’s infamous genocide began, and Nitegeka was compelled to once again flee into the unknown.

“I moved around Africa, in search of peace. I stayed in just about every country in Central Africa, and in Kenya. But always, for some or other reason, I had to move,” he said.

Nitegeka’s works are reflections of his decade-long experiences as a refugee and an asylum seeker. He said “…and walk in my shoes…” could be seen as a “metaphor that allows participators in it to feel just a little like people who are forced to migrate – trapped in strange cultures and foreign political and economic systems.”

All the harsh wooden beams, he said, could represent the mire of painful obstacles that asylum seekers must overcome in their attempts to secure peace and prosperity in foreign lands – including rebel and government soldiers, corrupt officials who demand bribes for safe and legal passage, and hostile populations in the places where they look for shelter.

“Like the experience of my latest installation, the migrant experience is one of discord and dislocation. I know, because I’ve lived it,” said Nitegeka.

He described his art as a battle to understand the identity of a “forced migrant…to understand the space that one finds him or herself in, given the condition of moving from one place to another and having to adapt to it.”

Nitegeka has received many prizes for his work, including South Africa’s prestigious Tollman Award for Visual Arts in 2010, and he’s exhibited around the world. But he insisted he remains unable to define himself as an artist.

“I really can’t say I’m a painter or a sculptor or anything like that. It’s more of I’m an installation artist, if you like. But even that, I kind of resist.”

Nitegeka bares all

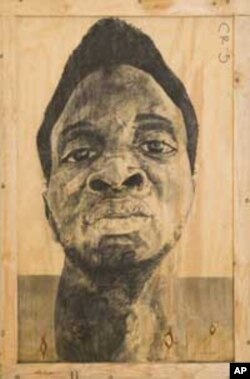

Nitegeka began making his mark in the international art world a few years ago when critics in South Africa lauded his very first installation. He’d titled it “Human Cargo.” To create it, he used wooden crates and decorated them with life-sized charcoal portraits of himself in the nude.

“I’d describe that as a very direct work. I used crates, and a body – mine – and I also used a title and the visuals of it that directly (allude) to the experience of forced migration. The installation clearly alluded to things like human trafficking and slavery.”

Nitegeka uses whatever material he’s able to find from whatever environment he happens to find himself in. He explained, “It’s not a matter of choice. It’s a matter of finding material. That’s how I work – I find material in space.”

That space is now South Africa, where he settled in 2003.

When a friend showed Nitegeka some wooden crates he’d found on the campus of Johannesburg’s Wits University, the artist said he immediately felt an “affinity” to the objects.

“When I find material like this, I sit and look at it for a long time. If I develop a kind of telekinesis between myself and the material, and it transforms before my eyes, then I use it,” he said. “Looking at the crates, I started thinking, ‘What would happen if I project myself onto the wood?’”

Nitegeka also put a lot of thought into which medium to use to sketch himself on the crates. He settled on charcoal. “Charcoal, conceptually and onto the wood, becomes a kind or bonding or re-bonding of matter, because charcoal was once wood. So that was going to be interesting,” he commented.

In “Human Cargo,” the Burundian creator said he’d “combined the history of the crates, with their history of being moved across borders, with the experience of being a forced migrant – people who are also moved across borders as human cargo.”

While much of Nitegeka’s work is autobiographical, he maintained that it “exists separately” from him. “It stands in its own world. My art and I are two different dualities. My art is what people look at and is what I want people to look at, not the person.”

He added, “Like most migrants, I’m actually invisible as a person, unimportant. But through my art, I become visible, and I find meaning and recognition. I’m fortunate.”

Security threat

Nitegeka’s work sometimes transcends mere autobiography and audience participation and becomes blatantly confrontational, as in the case of his “A Hundred Stools” project in 2010.

He got a lot of old pinewood and decided to make 100 stools from it. He wanted to give them to asylum seekers and refugees who were queuing for documentation at a South African government building in Johannesburg.

“It was a small attempt at giving significance to the asylum seekers, to humanize them, to give them a bit of dignity. These people wait in lines for weeks without a chair to sit on,” said Nitegeka.

He explained further: “I took my idea for this work from the symbol of an African stool. In Africa, no matter where you go, stools are always offered to visitors. The stool is a powerful symbol of making someone feel welcome and worthy.”

But Nitegeka’s project offended the South African authorities. Security officials prevented him from handing out the stools.

“I guess they saw the wooden stools as a security threat – a threat to their own security, that is,” he said. “They were probably angry with me because my actions in providing the stools made them feel ashamed at the way they were treating the refugees.”

Finally, however, the state officers did allow Nitegeka to give the chairs to the asylum seekers.

No safety

For 2012, the artist is planning some large works. “These days I can’t stop myself from thinking that I must create bigger and bigger installations,” he said. “It’s either you go big or you go home, you know. That’s how it is – not in the sense (of) things going big in your head, but what you do.”

Nitegeka also vowed to keep experimenting and “to never get safe” in terms of his art. As a final analysis of himself and his work, he said, “I suppose it’s because I’ve never had much stability in my life that my work is also so unstable, so unsafe. Even I don’t know what I’m going to do next.”

Then, with a deadpan expression on his face, he added, “I might even express myself in ballet someday.”

While Nitegeka clearly enjoys pushing boundaries and taking risks, it’s difficult to imagine the hulking former refugee, who’s more than two meters tall, and who wouldn’t look out of place guarding the door of a chic nightclub, dancing Swan Lake in tights and slippers.

“Hey, you never know,” he smiled. “You just never know.”