Russian historian Anatoly Razumov has been working for more than three decades to identify those who died in Joseph Stalin's purges. “We aren’t humans, if we don’t have memory,” he says.

As he bustles around his cramped office with floor-to-ceiling bookcases and papers stacked high everywhere, he assures VOA, “This room is well-organized, I can find everything I need very quickly.”

Razumov’s office, which can be discovered at the end of a series of narrow corridors and winding stairs in the National Library of Russia in St Petersburg, is a frontline in a battle being waged over history and the chronicling of the communist past.

Expunging Stalin’s crimes

Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin has slowly been rehabilitated since Vladimir Putin came to power, a rehabilitation that is growing apace with memorials once again being erected to Stalin and officials no longer embarrassed to hang portraits of the Soviet dictator.

Behind Razumov are rows of thick red-bound volumes of a collective research effort he has spearheaded to name those who were slaughtered in Stalin’s Great Terror. The victims were dispatched with a bullet to the back of the head, if lucky, or they died while being tortured or from malnutrition and freezing conditions in labor camps, where the so-called “enemies of the state” were dumped to “build socialism.”

The ledgers, which are being added to daily, also contain the names of those who died during the Nazi siege of Leningrad, the city renamed St. Petersburg after the fall of the Soviet Union. As he scurries about, he announces, “here’s a siege list.” “We have more than 900,000 names of people who went through the siege,” adds the man who has become the bookkeeper of terror.

And still the research goes on to detail the death toll of the communist purges and the siege of Leningrad. Names of men, names of women, names of children. Each name a blood-and-bone story of lives brutally snuffed out, of promise and hope denied, of children left as orphans, of spouses violently broken apart, of parents left to mourn sons and daughters.

Daring to remember

“I’m doing this job every day. So I have enough work to do,” says the gray-haired historian. “We need to remember. We are working for people who want to know and for the people who will want to know someday,” he says. The Kremlin doesn’t want to know. Now the very act of remembrance is frowned on with the authorities under President Putin seeing the memorializing as unpatriotic, an act undertaken by fifth columnists to the benefit only of Western enemies.

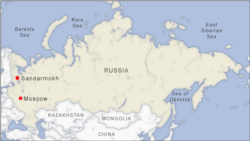

A key skirmish in the battle for history has centered on the mass grave at Sandarmokh, near the Finnish border, where Razumov and other Gulag historians say more than 6, 241 victims of Stalin’s Great Terror were shot and buried during 1937-38. They base their claims on field work and documents from the secret police archives, including the interrogation testimony of the executioners, who were later shot themselves.

Blaming the Finns

In August, there was brief state-sponsored excavation of the site by a Kremlin-sponsored organization called the Russian Military-Historical Society, RVIO, with the aim to prove that not everyone buried at Sandarmokh were Stalin’s victims. The RVIO excavators say some might have been Soviet soldiers, who were either shot by the Finnish while the territory was under their occupation in 1942-44 or who died while being held captive by the Finns.

The excavation team said they had not come to rewrite history and were merely testing a hypothesis that as the Finns held Soviet captives nearby, it was entirely feasible they had used the same killing ground. But at a press conference at Sandarmokh, Sergei Barinov, head of the excavation team, held up the official invitation letter for the dig from the Culture Ministry.

During the press conference an observer from Memorial, a rights organization dedicated to documenting Soviet-era purges, snapped the letter as Barinov waved it around. And in the letter, the Culture Ministry bewailed how Sandarmokh “damages the international image of Russia.”

The theory that Soviet prisoners of war may be buried at Sandarmokh was first broached by Sergey Verigin, director of the Institute of History at Petrozavodsk State University. He says he is not trying to deny Stalin’s victims are buried at the site, but he says his hypothesis is sensible, despite the fact it lacks any documentary evidence.

“I’m not going to rewrite Sandarmokh history, as some Russian liberal-democratic media accuse me of,” he told VOA. “My theory is that Soviet prisoners of war of the Finnish occupation might be buried there, too, though there are doubts also about the numbers in total buried there,” he adds.

In August, Finland’s National Archive issued a terse statement dismissing the RVIO hypothesis. “Finland has opened up its materials concerning [Soviet] POWs. These archival sources indicate that Soviet POWs were not buried at Sandarmokh,” the archive said.

In his university office, empty of books or papers, Verigin says much of the battle for history comes down to Gulag historians wanting to use the criticism of the Stalin era against Putin. “They are transferring their criticism to modern Russia, to Putin,” he says.

Razumov and other Gulag historians say RVIO is trying to muddy the history of Sandarmokh, by trying to get the Finns, who ran a POW camp nearby, to share the blame for the burial pits.

Uphill battle for the truth

The skirmishes over history are likely to intensify. Razumov says researching the Great Terror has always been difficult, even during the thaw years of Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin, Putin’s predecessor. He identifies 1997 as marking the start of the end of the thaw when it comes to the history of the Great Terror. In a presidential decree Yeltsin declared 1997 as the Year of Reconciliation. “After 1997 the topic was meant to go quiet. As far as the authorities were concerned the topic was finished,” says Razumov.

Ironically, 1997 was the year his good friend and colleague Stalin-era historian Yury Dmitriyev discovered through archival research and excavation the mass gravesite at Sandarmokh and another one at Krasny Bor, on the outskirts of the Karelian capital of Petrozavodsk. Dmitriyev is now in his third year in jail awaiting trial on what his family, friends and colleagues say are trumped-up charges of sexual assault on a minor.

“It was lucky those sites were found in 1997. It couldn’t be done now,” says Razumov. Access to departmental and state archives has become much more difficult — and often impossible. He says since the Revolution of 1917 there have been constants in the thinking of Kremlin authorities, who have a “fear of people, fear of truth and a fear of free discussion.”

“Which anthem do we use now? We use the anthem of Soviet Union, not Russia. On Red Square at the Kremlin, the people who were responsible for all of these atrocities, from Lenin’s Terror to Stalin’s bigger Great Terror, are honored and saluted,” he laments. History shouldn’t be re-written because it is politically convenient as “atrocities come from excuses,” Razumov says just before we navigate the stairs and narrow corridors out into the fresh air.