When Robert Blecker, a professor at New York Law School, first witnessed an execution, it reminded him of the scene when his father-in-law died in a hospice.

“In both cases, the dying person was wrapped in white sheets, lying on a gurney with an IV coming out of his arm, attended by medical technicians, with loved ones, and witness,” recalls Blecker who spent thousands of hours interviewing inmates in maximum-security prisons for his book of "The Punishment of Death."

The author is an unlikely opponent of a series of controversial executions underway in the southern U.S. state of Arkansas. While human rights advocates have voiced fear that a lethal drug cocktail used by authorities in Arkansas could botch the executions, Blecker says he opposes them because he is against lethal injection. And he opposes lethal injection not because “it causes pain but because it creates confusion.”

"It medicalizes punishment," Blecker says.

Instead, he prefers the firing squad, a method with no record of botched executions. But while opponents find it savage, Blecker says he has a problem with the way it is used: with one randomly selected shooter firing blanks at the convict, all squad members are allowed to later deny culpability for firing the fatal bullet.

‘Ashamed to punish’

“It shows we’re ashamed to punish,” says Blecker. Punishment “should be constructed as punishment and carried out as such.”

Lethal injection is by far the most common method of execution in the United States. Since 1973, 88 percent of 1,449 executions have been carried out by lethal injection, almost all using the same three-drug cocktail: the sedative midazolam to mask the pain; pancuronium bromide to paralyze and halt breathing; and potassium chloride to stop the heart.

But midazolam has been used in several flawed executions in recent years. In December, Ronald Smith, an Alabama convict, “heaved, gasped, and snorted for 13 minutes” before he was pronounced dead. His lawyer declared his death a “botched” execution.

Arkansas originally wanted to execute eight inmates over the course of four days by the end of April when its supply of midazolam expires. Last week the makers of midazolam and potassium chloride asked a federal judge to prevent Arkansas from using the drugs, saying they were not intended for capital punishment.

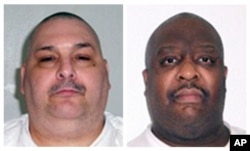

Fearing the executions would be bungled, death penalty opponents asked the courts to intervene. Four executions were stayed. Three were allowed to proceed, including a double execution on Monday, the first of its kind carried out by the state in 17 years. A fourth is scheduled for Thursday.

Divisive issue

Capital punishment has long been a divisive issue in the United States. While support has fallen to a 40-year low, Americans remain split, with 49 percent in favor and 42 percent against it, according to a 2016 Pew Research Center poll.

Arkansas Attorney General Leslie Rutledge defended the executions, saying they brought the victims’ families justice and peace.

Blecker described the Arkansas death row inmates as a rogue gallery of criminals convicted of crimes that “should have been death eligible” but he said he did not know the "mitigating circumstances."

Like most death penalty proponents, Blecker says he is a “retributivist,” an advocate of punishment as retribution. But he says retribution is often erroneously confused with revenge. “Retribution is limited, proportionate and appropriately directed,” he says.

In 95 percent of murder cases, he says he does not favor the death penalty. But the 5 percent of cases that he thinks deserve the death penalty include a killer "who had raped a woman, cut off her arms and legs and threw her body in the woods to die in the most agonizing pain imaginable."

Though the woman miraculously survived, "my view is that he deserves to die," Blecker says.

‘The innocence problem’

Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center in Washington, says retribution is a valid argument made by capital punishment supporters.

“For it to be valid, the death penalty has to accurately identify the individual who has to be subject to it," Dunham says. "And that has the innocence problem.”

According to Dunham's organization, since 1973, more than 155 people have been released from death row with evidence of their innocence often through the efforts of advocates Blecker says he supports.

Opponents also say that the death penalty is discriminatory, disproportionately targeting minorities. For example, a 2014 study found that jurors in Washington state are three times more likely to recommend a death sentence for a black defendant than for a white defendant in a similar case.

Meanwhile, all indicators point to a long-term decline in the practice of the death penalty in the United States. Last year there were 20 executions, the lowest since 1991 when 14 people were executed, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. Though 31 states have capital punishment laws, fewer and fewer states carry out executions.

“Even in states that have the death penalty, fewer counties are using it and the counties that are using it are using it less and less,” Dunham said. “We’re also seeing in cases that the prosecutors are seeing it, juries are returning it less and less.”