More than 180 human rights groups are calling for diplomatic boycott of the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympic Games to protest Beijing's abuses of racial and ethnic minorities.

The coalition of Tibetan, Uighur, Hong Kong, Taiwanese and human rights groups issued an open letter last week, calling on governments to boycott the 2022 Games "to ensure [the games] are not used to embolden the Chinese government's appalling rights abuses and crackdowns on dissent."

Such a so-called diplomatic boycott would involve the withdrawal of ambassadors during the 2022 Games and suspending consular functions February 4-20. The organizers believe this would send a message to Beijing. Their call came days before U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken pressed senior Chinese diplomat Yang Jiechi for accountability on human rights abuses, particularly in Xinjiang, Tibet and Hong Kong.

And more than a dozen Canadian lawmakers signed an open letter calling for the Olympics to be moved outside China, according to Canada's Global News website.

Chinese state-controlled media Global Times responded with an editorial that warned against boycotting the games, saying, "China will definitely retaliate fiercely."

Sophie Richardson, China director at Human Rights Watch, said that message is drastically different from the slogan "Beijing Welcomes You" when the country hosted the 2008 Summer Olympics.

"If the Chinese government spent as much energy ending human rights violations as it does on hostile propaganda, it might find that discussions about a boycott would fade," she told VOA via email.

'No impact whatsoever'

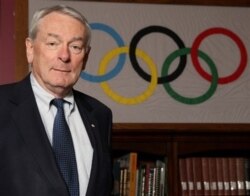

Other experts disagree with that stance. Canadian Dick Pound, the longest-serving member of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), said boycotting the games would be "a gesture that we know will have no impact whatsoever."

"The games are not Chinese Games, the games are the IOC Games," he told the BBC. "The decision on hosting is not made with a view to signaling approval of a government policy."

Linking human rights concerns to the 2022 Winter Olympics goes beyond the diplomatic into the rough-and-tumble of world-class athletes and sports fans.

In 2018, 1.92 billion people, or 28% of the world's population, watched the Winter Olympic Games in South Korea, held February 9-25, according to organizers.

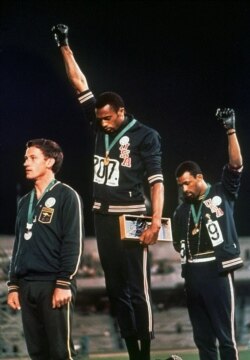

Using the games as a platform to advance human rights began after World War II with 200-meter sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos, gold and bronze medalists, respectively, in the 1968 Mexico City Games. At the awards ceremony, as the U.S. national anthem played, the men bowed their heads and raised a fist.

Since then, South Africa was expelled from the 1970 Games for the country's policy of apartheid. It was not readmitted to competition until the 1992 Barcelona Games. In 1980, 66 countries, led by the United States, boycotted the Moscow Games because of the Soviet Union's invasion of Afghanistan.

Daryl Adair, an associate professor of sports management at the University of Technology Sydney, told VOA via email that the IOC has a responsibility to be sure that the principles that underpin the Olympics are appropriately reflected in countries that host the games.

"For example, would the IOC and the international sporting community be comfortable with an Olympics hosted by Myanmar, given its treatment of the Rohingya people, followed more recently by a military coup?" he asked.

"China is, like Myanmar, a country for which external observers have serious and legitimate concerns – most notably with claims about Beijing's treatment of some ethnic minorities," Adair added.

Adair said that unless Beijing can demonstrate that such claims are without merit, calls to disallow Beijing from hosting the 2022 Olympics would continue. "And the IOC will be drawn irrevocably into a discussion it seems reluctant to have," he told VOA.

Rule 50

Currently, the International Olympic Committee's official stance is that it is only a sporting body that does not get involved with politics.

The committee points to Rule 50 of the Olympic Charter, which states, "No kind of demonstration or political, religious or racial propaganda is permitted in any Olympic sites, venues or other areas."

Yet, with athlete activism on the rise, the IOC Athletes' Commission is now consulting with athletes globally on different ways Olympians can express themselves in a "dignified way," with a recommendation on Rule 50 expected in early 2021.

Jules Boykoff, a political science professor at Pacific University, represented the U.S. on the Olympic soccer team from 1989 to 1992 before turning professional to play for the Portland Pride, Minnesota Thunder and Milwaukee Wave.

He told VOA, "The Chinese government's treatment of the ethnic Uighur Muslim population in Xinjiang province and its tough and brutal crackdown on the dissent in Hong Kong clash mightily with the principles that are enshrined in the Olympic Charter."

Boykoff, the author of Activism and the Olympics, told VOA that the IOC commission's review of Rule 50 is "absolutely necessary."

"It has long been outdated and it clashes with fundamental human rights principles such as (United Nations) Article 19, which states very clearly that one should be able to speak out with freedom on issues that matter to them," Boykoff said, adding that curtailing the freedom of speech actually clashes with ideas that are based in the Olympic Charter.

Many human rights groups welcome the review. "In the age of social media, it has had to review this rule," said Richardson, of Human Rights Watch. "We believe that the IOC should simply remove all barriers to peaceful expression."

Yet Adair said there might be a flip side to laissez-faire political speech and gestures on the field of play and during ceremonies if athletes advocate for causes that do not align with themes that the IOC endorses.

He took the recent Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement as an example.

"Advocating for a cause like BLM is consistent with the Olympic Charter," he said, "However, if an athlete advocated for white supremacy or ethnic cleansing, that would be inconsistent with the sport participation equity principles underlying the Olympic Movement."

He urged the IOC to provide guidelines consistent with the values it espouses for athlete participation because "this would also have the benefit of deterring political commentary that is not about human rights or social justice."

Yu Zhou from the VOA Mandarin Service contributed to this report.