It's not just that the doors of Europe are closing to refugees; for those who have survived sniper fire, minefields, swift-moving rivers and roadside bombs, just trying to get into overflowing refugee camps in their home countries is proving impossible.

They are among the record 65.3 million people worldwide displaced from their homes, according to the U.N. refugee agency, the UNHCR — a 10 percent increase over last year. Half of them are children.

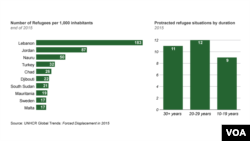

"Twenty-four people are displaced every minute," said UNHCR chief Filippo Grandi. "Two-thirds of the forcibly displaced are internally displaced. Ninety percent of the forcibly displaced are displaced in poor or middle-income countries, not in the rich world."

Close to 10 million of the world's refugees are Syrian. Three million have fled to neighboring countries; the rest are internally displaced within Syria.

While Syria remains the largest forcibly displaced crisis in the world, neighboring Iraq has been overwhelmed by people fleeing Islamic State-held territory.

"They've been eating rotting, expired dates and drinking from the river, which is unfit for drinking, and now they are finding themselves out there and we are unable to cope and help everyone," said Karl Schembri, a spokesman for the Norwegian Refugee Council in Baghdad.

For those who have found haven in the camps, an atmosphere of despair is descending. Like many others, the Harsham refugee camp in northern Iraq is taking on an air of permanence. Camp manager Ahmed Abdo says the residents have lost hope of returning home.

"The people have been trying to improve their life by adding more rooms to their living areas, including guest rooms, as well as other facilities attached to the house, because honestly these people have given up hope that they can go back to their homes and houses in the near future."

It's not just the Middle East. In Kenya, the Dadaab camp is slated for closure, leaving hundreds of thousands of Somali refugees in limbo.

"Young people, who have been living here for more than 25 years, whose only known home is here, are now worried about their future," says camp official Ruqiyo Ali Raage, noting that the prospect of returning to Somalia is raising alarms.

High commissioner Grandi tells VOA that new areas of displacement keep popping up. While Burundi has been in and out of conflict for decades, he says that over the past year, there has been a surge of internally displaced people and refugees.

"Then there are crises like South Sudan that have also gone through different phases. We are, unfortunately, in an upsurge phase," Grandi said. "There is a new movement out of Afghanistan. Even people that have been refugees in Iran for a long time — Afghans — are moving on."

During the past year, millions of refugees and migrants have tried to reach Europe, and the UNHCR is warning of a "climate of xenophobia" across the continent.

In May, 19,000 migrants came ashore in Italy from North Africa. The European Union is seeking to cooperate with Libyan coast guards to stem the flow, but that is not the right way to deal with the crisis, argues Gauri van Gulik of Amnesty International.

Grandi says that the huge numbers of people on the move carried an important message for the rich countries of Europe and beyond.

"If you don't solve problems, problems will come to you, and that is a powerful message,” Grandi said. “It is a painful message, and it is painful that it has taken so long for people in the rich countries to understand that, but I think it is a call for action.

"It's absolutely clear that Europe is not prepared, in the sense that it's focused purely on outsourcing of its responsibility again. It's just looking at how can we stop people from coming, rather than how do we create a managed flow of people, those who need protection, into Europe."

Latest figures show a continued sharp fall in the number of migrants traveling from Turkey to Greece. The deal struck in March between Brussels and Ankara means all new arrivals on the Greek islands are supposed to be sent back to Turkey. Critics say the European Union is trying to create a "Fortress Europe." Among those critics is Serafeim Seferiadis of Panteion University in Athens.

"The idea has not been how to implement the secure passage of people, how to end drownings and killings and all that,” Seferiadis said. “Because if that were the objective, it would have been very easy to solve, because the refugee population, no matter how large it is and it is obviously very large, one must remember that it's less than one percent of the European population."

European ministers who met Monday in Luxembourg said the regional grouping is dealing with the refugee crisis. They added that it is vital to work with third-world countries like Libya and Turkey to address the problem.

The U.N. refugee agency said it is inevitable more people will try to reach Europe because of global inequality in wealth and security.

The United States says it will try to do its part. The State Department noted that the U.S. contributed $6 billion in humanitarian aid last year, and promised to boost refugee resettlement from nearly 70,000 people admitted in 2015 to 85,000 this year.

Sharon Behn in Irbil, Iraq, and Pamela Dockins, Victor Beattie and Mohamed Olad in Washington in the VOA Somali service contributed to this report.