DAKAR, SENEGAL —

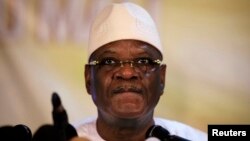

Mali's president-elect Ibrahim Boubacar Keita says he will reconcile, reunite and rebuild the country after 18 months of crisis and conflict. Keita doesn't take office for another two weeks, but his to-do list is already long and Malians are eager for results.

Ibrahim Boubacar Keita takes office September 4th on a tidal wave of popularity.

The one-time prime minister and former president of the National Assembly won the August 11th run-off election with 77 percent of votes.

In his first public declaration as president-elect, Keita said he would be the "president of all Malians."

"I will be the president of national reconciliation. This reconciliation is necessary to deal with the demands of our people: to rebuild the state and the rule of law, to fix the army and the education system, to fight corruption and to foster economic and social development. I will be the president to rebuild the nation," said the president-elect.

Keita said Wednesday that it would be a "new era." Even so, he is inheriting some hefty problems.

A Tuareg rebellion that began in January 2012 is still rumbling in the far north. Mali is now host to a massive U.N. mission to stabilize the north after a nine-month occupation by armed extremist groups who tried to set up their version of an Islamic state.

The leaders of the March 2012 military coup are still lurking around the foreground in Bamako. One of the final acts of the interim government was to promote coup leader Captain Amadou Sanogo to the rank of general.

Keita won the presidency thanks to a large and complex web of support from Muslim religious leaders, the military and most of his first-round rivals. His campaign always maintained that Keita was not cutting deals in exchange for votes.

But analysts said it could be difficult to manage all those alliances once in office. Malians are watching closely to see who Keita names to his cabinet.

Keita said Wednesday his government would be a meritocracy, not one guided by political or family alliances.

"Let me be clear. There is no question of sharing out the cake. I have not promised that and it will not happen," he said.

But actions speak louder than words, even the tough talk that Keita is known for. When asked what the country needed, voters often used the French verb "assainir," which means to flush out, to decontaminate, to clean up. They wanted to see Keita tackle the root causes of the crisis.

At the top of that list were the pervasive corruption and patronage that analysts said undermined development, crippled the army and ultimately handed the north over to criminal and terrorist groups.

Keita has pledged "zero tolerance" for corruption, but analysts say he must prove it, and fast, by doing what previous governments in Mali have not, by investigating and punishing those embezzling public resources. Something analysts say could be a hard pill to swallow for some of his political allies.

Security is the other key challenge.

Keita will have 60 days to open up what promise to be difficult negotiations with armed Tuareg separatist group, the MNLA, and its allies in the far northern region of Kidal. This Tuareg rebellion is the fourth of its kind since Mali became a country in 1960. Many say it is up to Keita to make it the last.

Those negotiations will be just one part of returning security and state authority to the formerly occupied north, where violence has forced hundreds of thousands to flee their homes and decimated the economy.

Ibrahim Boubacar Keita takes office September 4th on a tidal wave of popularity.

The one-time prime minister and former president of the National Assembly won the August 11th run-off election with 77 percent of votes.

In his first public declaration as president-elect, Keita said he would be the "president of all Malians."

"I will be the president of national reconciliation. This reconciliation is necessary to deal with the demands of our people: to rebuild the state and the rule of law, to fix the army and the education system, to fight corruption and to foster economic and social development. I will be the president to rebuild the nation," said the president-elect.

Keita said Wednesday that it would be a "new era." Even so, he is inheriting some hefty problems.

A Tuareg rebellion that began in January 2012 is still rumbling in the far north. Mali is now host to a massive U.N. mission to stabilize the north after a nine-month occupation by armed extremist groups who tried to set up their version of an Islamic state.

The leaders of the March 2012 military coup are still lurking around the foreground in Bamako. One of the final acts of the interim government was to promote coup leader Captain Amadou Sanogo to the rank of general.

Keita won the presidency thanks to a large and complex web of support from Muslim religious leaders, the military and most of his first-round rivals. His campaign always maintained that Keita was not cutting deals in exchange for votes.

But analysts said it could be difficult to manage all those alliances once in office. Malians are watching closely to see who Keita names to his cabinet.

Keita said Wednesday his government would be a meritocracy, not one guided by political or family alliances.

"Let me be clear. There is no question of sharing out the cake. I have not promised that and it will not happen," he said.

But actions speak louder than words, even the tough talk that Keita is known for. When asked what the country needed, voters often used the French verb "assainir," which means to flush out, to decontaminate, to clean up. They wanted to see Keita tackle the root causes of the crisis.

At the top of that list were the pervasive corruption and patronage that analysts said undermined development, crippled the army and ultimately handed the north over to criminal and terrorist groups.

Keita has pledged "zero tolerance" for corruption, but analysts say he must prove it, and fast, by doing what previous governments in Mali have not, by investigating and punishing those embezzling public resources. Something analysts say could be a hard pill to swallow for some of his political allies.

Security is the other key challenge.

Keita will have 60 days to open up what promise to be difficult negotiations with armed Tuareg separatist group, the MNLA, and its allies in the far northern region of Kidal. This Tuareg rebellion is the fourth of its kind since Mali became a country in 1960. Many say it is up to Keita to make it the last.

Those negotiations will be just one part of returning security and state authority to the formerly occupied north, where violence has forced hundreds of thousands to flee their homes and decimated the economy.