The building is completely anonymous - big, square and built with brick the color of milk chocolate. It sits in the middle of an industrial section in Allentown, Pennsylvania, a city that once hid the Liberty Bell from the British.

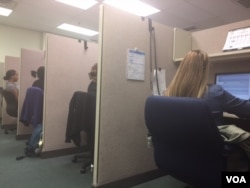

But inside are hundreds of telephone interviewers, conducting as many as 20 public opinion polls on subjects ranging from public health to consumer products to political candidates.

You might expect a big, chaotic room, but instead, it is rather quiet. Individual cubicles keep sound to a minimum. As you walk down aisle after aisle, a sing-songy refrain is heard over and over again.

"For this next question..."

"Using a ten point scale..."

"For quality insurance purposes, the call may be recorded..."

Survey research firm SSRS has partnered with ABC, CBS, the New York Times and other organizations to survey the U.S. public on its election choices. On behalf of ABC News, SSRS has conducted an average of one poll every week since August to measure support for the presidential candidates.

How it works

SSRS calls phone numbers at random and asks the same questions verbatim to each respondent. Any deviation from the question will invalidate the statistical accuracy of the survey.

"Questions are the portal into the minds of people who are answering them," says David Dutwin, SSRS executive vice president and chief methodologist. So transferring answers to the computer is vital for accuracy. Dutwin says 1000 participants must be documented because a sample of that size likely reflects the same demographic breakdown as the U.S. population. The combined results carry a 3% margin of error.

After 'hello'

"How about this evening around six?" interviewer Russell Lance asks someone on the other end of the line, who doesn't have enough time to answer his questions. Lance is a retired chemist who has spent eight years asking Americans about their habits and beliefs. He says people are usually very opinionated, especially about politics.

But even with the strong feelings, response is low. "I'd say if you get 10% of your contacts, you're lucky," says Lance, whose low estimate isn't far from reality. Recent surveys by Pew Research show response rates have leveled out at around 9%.

People are busy. Or can't be bothered. Or, the phone call leads to a non-working number.

Polling heyday

Political opinion polling enjoyed its highest responses in the 1970's, when most Americans owned several landlines in their homes. In addition, women then were typically at home during the day, with the entire family available during dinnertime. After the social unrest of the 1960's, people willingly offered their opinions.

But today, only about half of all Americans have home phones, whereas 9 out of 10 have cell phones. U.S. law doesn't allow companies to call cell phones with recorded messages, so firms like Pew and SSRS must employ live telephone interviewers for a mixture of landline and cellphone calls. Dutwin says it's expensive to pay 300 interviewers but it's cheaper than doing door-to-door surveys.

"And," continues Dutwin, "internet surveys aren’t reliable and don’t have the history to really trust them. So telephone interviews is the Goldilocks (perfect place) in the middle."

Even the middle has its challenges. Dutwin says his interviewers have to call 40 different people to get one person to agree to answer questions.

Not a 'sales call'

"I would like like to assure you this is not a sales call," says 19-year old Valentina Martinez through her headsets. Martinez says her biggest problem is convincing people she's not selling anything. It's a problem for all poll firms, like Pew Research, which conducts 30 polls each year.

Courtney Kennedy, who is head of research, says: "We're just trying to conduct a poll and trying to get their voice heard, but people assume that we're marketers."

But Kennedy agrees with Dutwin that telephone polling is the best method. Her company conducts 25% of its interviews on landline and 75% via cell phone. She says, while mobile phones offer unique challenges, it's only through them that previously unreachable groups are reachable. "Such as young adults, African Americans, Hispanics, that we have to struggle to reach on landlines.”

Still some people avoid the questions and hang up on the interviewers. Dutwin deplores this attitude with a mantra he repeats regularly. "Doing a survey is an opportunity to participate in a democracy. It’s a shame that some people pass on that opportunity."