Native Americans

Racism, 'Morbid Curiosity' Drove US Museums to Collect Indigenous Remains

In December 1900, John Wesley Powell received “the most unusual Christmas present of any person in the United States, if not in the world,” reported the Chicago Tribune.

The gift for this first director of the Smithsonian Institution’s Bureau of Ethnology was a sealskin sack containing the mummified remains of an Alaska Native.

The sender was a government employee hired to hunt Indian “relics,” who said the remains had been difficult to acquire because “to come into the possession of a dead Indian is a great crime among the Indians.”

The report concluded that it was the only “Indian relic" of this kind at the Smithsonian and it was “beyond money value.”

As it turned out, it was not the museum’s only Alaskan mummy. In 1865, even before the U.S. purchased Alaska from Russia, Smithsonian naturalist William H. Dall was hired to accompany an expedition to study the potential for a telegraph route through Siberia to Europe. In his spare time, he looted graves in the Yukon and caves on several Aleutian Islands.

After the U.S. sealed the deal with Russia, the San Francisco-based Alaska Commercial Company won exclusive trading rights and established more than 90 trading posts in Alaska to meet the U.S. demand for ivory and furs.

It also instructed agents “to collect and preserve objects of interest in ethnology and natural history” and forward them to the Smithsonian. Ernest Henig looted 12 preserved bodies and a skull from a cave in the Aleutians in 1874. He donated two to California’s Academy of Science and sent the remainder to the Smithsonian.

More than 30 years after the passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act meant to return those remains, a ProPublica investigation last year estimated that more than 110,000 Native American, Native Hawaiian and Alaska Native ancestors remain in public collections across the U.S.

It is not known how many Indigenous remains are closeted in private or overseas collections.

“Museums collected massive numbers, perhaps even millions,” said anthropologist John Stephen “Chip” Colwell, who previously served as curator of anthropology at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science. “Out of the 100 remains we [at the Denver museum] returned, I think only about five or seven individuals were actually even studied.”

So, what sparked this 19th-century frenzy for collecting human remains?

Reconciling science, religion

From the moment they first encountered Indigenous Americans, European thinkers struggled to understand who they were, where they came from, and whether they could be “civilized.”

The Christian bible taught them that all humans descended from Adam and that God created Adam in his own image. So why, Europeans wondered, did Native Americans, Africans and Asians look different?

Some Europeans theorized that all humans were created white, but dietary or environmental differences caused some of them to turn “brown, yellow, red or black.”

Other Europeans refused to accept that they shared a common ancestor with people of color and theorized that God created the races separately before he created Adam.

The birth of scientific racism

Presumptions that compulsory education and Christianization would force Native Americans to abandon their traditional cultures and become “civilized” into mainstream European-American culture proved untrue. So 19th-century scientists turned to advancements in medicine to “prove” the inferiority of Indigenous peoples.

“That’s when you see scientists like Samuel Morton, who invented a pseudoscience trying to place peoples within these social hierarchies based on their biology, and they needed bones to solidify those racial hierarchies,” said Colwell, who is editor-in-chief of the online magazine SAPIENS and author of “Plundered Skulls and Stolen Spirits: Inside the Fight to Reclaim Native America's Culture.”

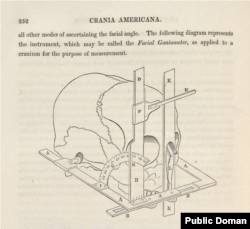

Morton was a Philadelphia physician who collected hundreds of human skulls of all races, mostly Native American, that were forwarded to him by physicians on the frontier. In his 1839 book "Crania Americana," Morton classified human races based on skull measurements. Morton's conclusions were used to support racist ideologies about the inferiority of non-white humans.

“They are not only averse to the restraints of education, but for the most part incapable of a continued process of reasoning on abstract subjects,” he wrote of Native Americans. “The structure of [the Native] mind appears to be different from that of the white man, nor can the two harmonise in their social relations except on the most limited scale.”

Despite Morton’s legacy as an early figure in scientific racism — ideologies that generate pseudo-scientific racist beliefs — his work earned him a reputation at the time as “a jewel of American science” and influenced the field of anthropology and public policy for decades.

In 1868, for example, the U.S. Surgeon General turned his attention away from the Civil War to the so-called “Indian wars” and instructed field surgeons to collect Native American skulls and weapons and send them to the Army Medical Museum in Washington “to aid in the progress of anthropological science.”

“For museums, especially the early years of collecting, it was a form of trophy keeping, a competition between museums,” Colwell told VOA. “And some of it was a competition between national governments to accumulate big collections to demonstrate their global and imperial aspirations.”

All the rest, he said, were fragments of morbid curiosity.

See all News Updates of the Day

US forest managers finalize land exchange with Native American tribe in Arizona

U.S. forest managers have finalized a land exchange with the Yavapai-Apache Nation that has been decades in the making and will significantly expand the size of the tribe's reservation in Arizona's Verde Valley, tribal leaders announced Tuesday.

As part of the arrangement, six parcels of private land acquired over the years by the tribe will be traded to the U.S. Forest Service in exchange for the tribe gaining ownership of 12.95 square kilometers of national forest land that is part of the tribe’s ancestral homelands. The tribe will host a signing ceremony next week to celebrate the exchange, which was first proposed in 1996.

“This is a critical step in our history and vital to the nation’s cultural and economic recovery and future prosperity,” Yavapai-Apache Chairwoman Tanya Lewis said in a post on the tribe's website.

Prescott National Forest Supervisor Sarah Clawson said in a statement that there had been many delays and changes to the proposal over the years, but the tribe and the Forest Service never lost sight of developing an agreement that would benefit both public and tribal lands.

The federal government has made strides over recent years to protect more lands held sacred by Native American tribes, to develop more arrangements for incorporating Indigenous knowledge into management of public lands and to streamline regulations for putting land into trust for tribes.

The Yavapai-Apache Nation is made up of two distinct groups of people — the Wipuhk’a’bah and the Dil’zhe’e. Their homelands spanned more than 41,440 square kilometers of what is now central Arizona. After the discovery of gold in the 1860s near Prescott, the federal government carved out only a fraction to establish a reservation. The inhabitants eventually were forced from the land, and it wasn't until the early 1900s that they were able to resettle a tiny portion of the area.

In the Verde Valley, the Yavapai-Apache Nation's reservation lands are currently comprised of less than 7.77 square kilometers near Camp Verde. The small land base hasn't been enough to develop economic opportunities or to meet housing needs, Lewis said, pointing to dozens of families who are on a waiting list for new homes.

Lewis said that in acknowledgment of the past removal of the Yavapai-Apache people from their homelands, the preamble to the tribal constitution recognizes that land acquisition is among the Yavapai-Apache Nation's responsibilities.

Aside from growing the reservation, the exchange will bolster efforts by federal land managers to protect the headwaters of the Verde River and ensure the historic Yavapai Ranch is not sold for development. The agreement also will improve recreational access to portions of four national forests in Arizona.

On Navajo Nation, push to electrify more homes on vast reservation

After a five-year wait, Lorraine Black and Ricky Gillis heard the rumblings of an electrical crew reach their home on the sprawling Navajo Nation.

In five days' time, their home would be connected to the power grid, replacing their reliance on a few solar panels and propane lanterns. No longer would the CPAP machine Gillis uses for sleep apnea or his home heart monitor transmitting information to doctors 400 miles away face interruptions due to intermittent power. It also means Black and Gillis can now use more than a few appliances — such as a fridge, a TV, and an evaporative cooling unit — at the same time.

"We're one of the luckiest people who get to get electric," Gillis said.

Many Navajo families still live without running water and electricity, a product of historic neglect and the struggle to get services to far-flung homes on the 70,000-square-kilometer (27,000-square-mile) Native American reservation that lies in parts of Arizona, New Mexico and Utah. Some rely on solar panels or generators, which can be patchy, and others have no electricity whatsoever.

Gillis and Black filed an application to connect their home back in 2019. But when the coronavirus pandemic started ravaging the tribe and everything besides essential services was shut down on the reservation, it further stalled the process.

Their wait highlights the persistent challenges in electrifying every Navajo home, even with recent injections of federal money for tribal infrastructure and services and as extreme heat in the Southwest intensified by climate change adds to the urgency.

"We are a part of America that a lot of the time feels kind of left out," said Vircynthia Charley, district manager at the Navajo Tribal Utility Authority, a non-for-profit utility that provides electric, water, wastewater, natural gas and solar energy services.

For years, the Navajo Tribal Utility Authority has worked to get more Navajo homes connected to the grid faster. Under a program called Light Up Navajo, which uses a mix of private and public funding, outside utilities from across the U.S. send electric crews to help connect homes and extend power lines.

But installing power on the reservation roughly the size of West Virginia is time-consuming and expensive due to its rugged geography and the vast distances between homes. Drilling for power poles there can take several hours because of underground rock deposits while some homes near Monument Valley must have power lines installed underground to meet strict regulations around development in the area.

About 32% of Navajo homes still have no electricity. Connecting the remaining 10,400 homes on the reservation would cost $416 million, said Deenise Becenti, government and public affairs manager at the utility.

This year, Light Up Navajo connected 170 more families to the grid. Since the program started in 2019, 882 Navajo families have had their homes electrified. If the program stays funded, Becenti said it could take another 26 years to connect every home on the reservation.

Those that get connected immediately reap the benefits.

Until this month, Black and Gillis' solar panels that the utility installed a few years ago would last about two to three days before their battery drained in cloudy weather. It would take another two days to recharge.

"You had to really watch the watts and whatever you're using on a cloudy day," Gillis said.

Then a volunteer power crew from Colorado helped install 14 power poles while the tribal utility authority drilled holes six feet deep in which the poles would sit. The crew then ran a wire about a mile down a red sand road from the main power line to the couple's home.

"The lights are brighter," Black remarked after her home was connected.

In recent years, significantly more federal money has been allocated for tribes to improve infrastructure on reservations, including $32 billion from the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 — of which Navajo Nation received $112 million for electric connections. The Navajo tribal utility also received $17 million through the Biden administration's climate law, known as the Inflation Reduction Act, to connect families to the electric grid. But it can be slow to see the effects of that money on the ground due to bureaucracy and logistics.

Next spring, the tribal utility authority hopes to connect another 150 homes, including the home of Priscilla and Leo Dan.

For the couple, having grid electricity at their home near Navajo Mountain in Arizona would end a nearly 12-year wait. They currently live in a recreational vehicle elsewhere closer to their jobs but have worked on their home on the reservation for years. With power there, they could spend more time where Priscilla grew up and where her dad still lives.

It would make life simpler, Priscilla said. "Because otherwise, everything, it seems like, takes twice as long to do."

Native Americans react to Biden apology as a good ‘first step’

President Joe Biden visited the Gila River Indian Community in Arizona on Friday to deliver a long-awaited official apology to Native Americans for the federal boarding school system that severed the family, tribal and cultural ties of thousands of Indian children over multiple generations.

“I say this with all sincerity: This, to me, is one the most consequential things I've ever had an opportunity to do in my whole career as president of the United States,” Biden said.

He described how Native children were “stolen, taken away to places they didn't know by people they'd never met who spoke a language they had never heard,” he said.

“Children would arrive at school, their clothes taken off, their hair that they were told [was] sacred was chopped off, their names literally erased and replaced by a number or an English name,” he continued, “emotionally, physically and sexually abused, forced into hard labor, some put up for adoption without the consent of their birth parents, some left for dead in unmarked graves.”

When the time came to apologize, Biden shouted the words, “I formally apologize!”

Mixed reactions

In 2021, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland launched an investigation into federal and federally funded Indian boarding schools. The investigation confirmed that more than 18,600 Native American, Native Alaskan and Native Hawaiian children were forced to attend residential schools; 1,000 died during their enrollment.

The report recommended the U.S. government formally acknowledge and apologize for its role in the system and take steps to help survivors heal from its effects.

VOA spoke with Christine Diindiisi McCleave, a citizen of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians in North Dakota and former CEO of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS), which collaborated with the Interior investigation.

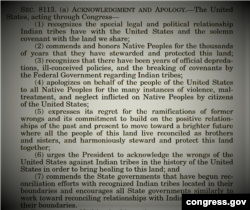

“I think politically it is extremely significant that Biden traveled to tribal lands in Gila River to deliver the apology publicly, not bury it in a defense appropriations bill,” she said, referencing a 2009 defense spending bill that acknowledged “years of official depredations, ill-conceived policies and the breaking of covenants” and apologized for instances of “violence, maltreatment and neglect.”

“However, as a survivor, as somebody who worked for many years to make progress on this issue, yes, we need the acknowledgment, but we also need actions to follow that up,” she said.

Friday’s apology came late in Biden’s term. McCleave said she worried that a Republican win in the November 5 presidential vote could reverse the gains for tribes made during the Biden-Harris administration.

“I hope they pass the Truth and Healing Commission bill before the new term begins,” she said.

The bipartisan Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies Act, currently making its way through Congress, would create a commission to investigate the boarding school system and recommend action to promote healing.

Schools only part of the story

On Friday, Biden summarized his investments in Indian Country, which include $32 billion from the American Rescue Plan, $13 billion to support improvements in tribal infrastructure and $700 million from the Inflation Reduction Act to combat the effects of climate change.

He did not, however, address growing calls from Native communities for the return of historic lands, a campaign dubbed “Land Back.”

Brenda J. Child, a citizen of the Red Lake Band of Chippewa in Minnesota, is a professor of American studies at the University of Minnesota who has written extensively about Indian boarding schools from the perspective of Indigenous Americans.

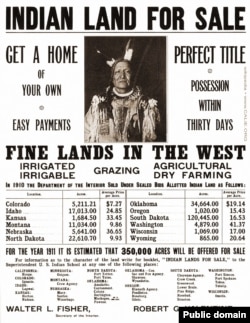

“Boarding schools were about dispossessing Indian people of their lands,” she said, “which went hand in hand with the complex policy called the General Allotment Act of 1887, which helped break up the traditional systems of land tenure.”

Also known as the Dawes Act, it divided Native Americans’ communal tribal lands into individual plots that were doled out to families and individuals. The leftover land – about 36 million hectares (90 million acres) – was opened up for sale to non-Native settlers, passing out of Indian control.

“So, what do we do now?” Child asked. “Apologies are nice, but if you don't change the behavior, we're still stuck. Now it's time to return some of that land that we lost.”

Watch Biden’s entire speech below:

One of the last Navajo Code Talkers from World War II dies at 107

John Kinsel Sr., one of the last remaining Navajo Code Talkers who transmitted messages during World War II based on the tribe's native language, has died. He was 107.

Navajo Nation officials in Window Rock announced Kinsel's death on Saturday.

Tribal President Buu Nygren has ordered all flags on the reservation to be flown at half-staff until Oct. 27 at sunset to honor Kinsel.

"Mr. Kinsel was a Marine who bravely and selflessly fought for all of us in the most terrifying circumstances with the greatest responsibility as a Navajo Code Talker," Nygren said in a statement Sunday.

With Kinsel's death, only two original Navajo Code Talkers are still alive: Former Navajo Chairman Peter MacDonald and Thomas H. Begay.

Hundreds of Navajos were recruited by the Marines to serve as Code Talkers during the war, transmitting messages based on their then-unwritten native language.

They confounded Japanese military cryptologists during World War II and participated in all assaults the Marines led in the Pacific from 1942 to 1945, including at Guadalcanal, Tarawa, Peleliu and Iwo Jima.

The Code Talkers sent thousands of messages without error on Japanese troop movements, battlefield tactics and other communications crucial to the war's ultimate outcome.

Kinsel was born in Cove, Arizona, and lived in the Navajo community of Lukachukai.

He enlisted in the Marines in 1942 and became an elite Code Talker, serving with the 9th Marine Regiment and the 3rd Marine Division during the Battle of Iwo Jima.

President Ronald Reagan established Navajo Code Talkers Day in 1982 and the Aug. 14 holiday honors all the tribes associated with the war effort.

The day is an Arizona state holiday and Navajo Nation holiday on the vast reservation that occupies portions of northeastern Arizona, northwestern New Mexico and southeastern Utah.

Native American news roundup Oct. 13 – 19, 2024

Indigenous Peoples Day and Columbus Day observed Monday

Some Americans this week celebrated Christopher Columbus’ October 1492 landing in the Western Hemisphere while others marked the alternative Indigenous Peoples’ Day commemorating the exploitation that began with Columbus’ arrival, which ultimately led to widespread displacement, violence, disease and enslavement.

The U.N. Committee on Non-Governmental Organizations in 1977 held the first International NGO Conference on Discrimination against Indigenous Populations in the Americas in Geneva. Attending delegates from Indigenous nations passed a resolution to recognize an “International Day of Solidarity with the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas.”

President Joe Biden in 2021 recognized Indigenous Peoples Day as a national — but not a federal — holiday. Today, more than two dozen states and many cities across the U.S. observe the day with powwows and other cultural events.

About 2,000 people gathered at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles to celebrate. VOA reporter Genia Dulot was there and filed this report:

Tribal protesters clash with police in nation’s capital

In Washington, D.C., the Indigenous People’s Day holiday brought confrontation between U.S. Park Police and protesters from the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe of California, who rode across the country on horseback along a "Trail of Truth" to lobby for federal recognition that the Interior Department's Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) denied decades ago.

The tribe claims descent from the Verona Band of Alameda County, which inhabited the San Francisco Bay Area for over 10,000 years.

In 1989 they petitioned the BIA for federal acknowledgment as the “Ohlone/Costanoan Muwekma Tribe.” The BIA rejected their application, citing a lack of evidence showing the tribe had continuously operated since 1927 as the same or an evolved tribal entity previously acknowledged.

Protests involving 25 or more people on the National Mall or other National Park Service (NPS)-controlled areas require a permit, which the group had not obtained. Tensions escalated when police attempted to remove the group and their horses.

"The Department of the Interior's posture with Native peoples is on full display," the group posted onFacebook. "Was Indian Country naive to think that Indigenous leadership at the top was going to change the institutional culture, colonial legal architecture, and systems of oppression that have always been the core function of the Department?"

In a statement to VOA, the NPS said the group has since dismantled their camp and submitted a permit application, which is under review.

"However, enforcement actions were taken, including the arrest of one person on October 16 for assaulting a police officer and other violations. On October 15, USPP officers arrested nine others for similar offenses," the statement said.

Minnesota tribe is latest to sue social media companies

CBS News reports this week that the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa in Minnesota has joined four other tribes in a lawsuit against social media giants including Instagram, Snapchat, TikTok and YouTube for allegedly harming a Native American youth's mental health.

The 164-page complaint alleges that parent companies including Alphabet, ByteDance, Meta and Snap violated Minnesota laws by failing to warn users about the negative mental health effects of social media, particularly for children.

“They [Native teenagers] are more vulnerable because they've struggled with mental health because of isolation and poverty on some of the reservations,” attorney Tim Purdon, a partner in the law firm that filed the complaint, said during an interview in late July. “We seek dollars from them to be paid in our case directly to tribes to help abate or blunt or help fix the public mental health crisis that has resulted.”

Read more:

Navajo president calls for VP to resign

Navajo Nation president Buu Nygren has stripped Navajo vice president Richelle Montoya of her responsibilities and is calling for her resignation.

The announcement follows months of political tension within the tribe. In April, Montoya publicly accused the administration of intimidation and sexual harassment that she alleges took place during an August 2023 meeting in the president's office.

This prompted the tribal attorney to call for an independent investigation, which is still under way.

Nygren defended his actions in a news conference Tuesday, accusing the vice president of neglecting her official duties. He also cited Montoya’s decision to support a campaign to recall him as tribal leader.

“I welcome her resignation to make room for someone who wants to be a part of this administration,” Nygren said.

The rift between Nygren and Montoya has caused significant political upheaval, with tribal leaders and community members divided over the issues, further complicating governance and stability within the Navajo Nation.

Read more:

Lakota artist cites free speech rights, sues Colorado town

Danielle SeeWalker, a Hunkpapa Lakota artist from the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, is suing the town of Vail, Colorado, after her artist residency was canceled.

As VOA reported in May, SeeWalker posted a painting titled “G is for Genocide” on Instagram. It showed a near-faceless woman wearing a feather and a keffiyeh, the traditional Bedouin headscarf that has become the symbol for solidarity with Palestinians.

“It is about me expressing the parallels between what is happening to the innocent people in Gaza ... to that of the genocide of Native American populations here in our lands,” SeeWalker wrote in her post.

The town of Vail said in a May Facebook post that its decision to cancel her residency “was not made in a vacuum; after releasing her name in an announcement, community members, including representatives from our local faith-based communities, raised concerns to town staff around SeeWalker's recent rhetoric on her social media platform about the Hamas-Israel war.”

Backed by the American Civil Liberties Union, SeeWalker claims her First Amendment rights were violated and is seeking damages.

Read more: