The man who hosted the meeting that ended the Soviet Union is proud to say he was first to sign the declaration, known as the Belavezha Accords, followed by Russia’s Boris Yeltsin and Ukraine’s Leonid Kravchuk.

“I did not think about it when I was signing, but when I studied the 'Yugoslavia variant,' I am pretty convinced that we prevented civil war on the territory of the Soviet Union,” says Stanislav Shushkevich to VOA in his home office.

Surrounded by books and photos of former world leaders, Shushkevich flips through photo albums from the time, recalling why he convened the meeting 25 years ago. “The problem is that we got together not at all to adopt such a document. We had to solve the most vital and tough issue, how to survive during the winter of 1991-92. And I invited Yeltsin to the Belovezhskaya Puscha (park) for hunting. Well, it was clear that it was not just for hunting, but to convince him to supply us with oil and gas.”

As the men were looking at the legal obstacles to making such an energy deal, Shushkevich says Gennady Burbulis, later deputy prime minister of the Russian Federation, suggested an easy solution, declaring the USSR no longer exists.

The Soviet Union’s last leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, told Russia’s Interfax news agency this month the men wanted to get rid of him and were power hungry.

“Complete rubbish! I was never obsessed to hold power,” says Shushkevich. “And believe me, I could have maintained power, but I would have acted against my conscience.”

Sushkevich became the first leader and head of state of independent Belarus, but in 1994 lost in the presidential election to Alexander Lukashenko, who has been president ever since.

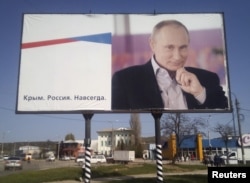

Russia’s President Vladimir Putin has called the collapse of the Soviet Union the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century.

“It is not the Soviet Empire that he wants to restore, but the Russian one,” argues Shushkevich. “He wants to make Russia dominate those lands and those countries that it used to dominate.”

Many in former Soviet bloc states worry that Putin’s actions in Ukraine show how far he is willing to go.

Russia defends its annexation of Crimea as following the will of the people there, and denies meddling in its neighbors' affairs.

"I am absolutely not concerned about that (here),” says Shushkevich. “Because it was already done in Belarus. Russia has got all the tools of power here and manages our illegitimate president (Alexander Lukashenko) the way it wants.”

Shushkevich cites the Russian military operating in Belarus as well as continued dependence on Russian oil and gas.

President Lukashenko and his staff weren't available to discuss Shushkevich's views when VOA requested interviews. But his supporters say Lukashenko is balancing relations with Russia and the West to the benefit of Belarus by negotiating supplies of cheaper energy and access to international financing.

The availability of Russian state television, with its pro-Kremlin, anti-West stance, in Belarus also affects public perceptions of Russia and the former Soviet Union.

As long as Russian state propaganda continues, says Shushkevich, it will be difficult for the region to come to terms with the Soviet Union’s collapse and develop the country’s politics.

“Belarusians live in a [political] situation that is pretty similar to that of the Soviet Union,” he says. “It is possible here to be a dissident, but normal opposition activities are impossible because it is called a ‘crime’ and we’ve had very many political prisoners.”