The printing and copying business run by Zynne Sibika and Gao Mokone in Johannesburg is sandwiched between a fast food outlet and a gas station. Inside the building, the pungent aroma of fried chicken and fuel mingles with the smell of new paper.

“Times have been tough for us kwaito people lately,” Sibika says, somewhat forlornly. “So we have had to diversify into other businesses in order to keep ourselves afloat,” he adds, pointing towards rows of humming photocopying machines, computers and printers.

In the 1990s, Sibika – who’s still known as the artist “Mahoota” – was on the cusp of one of the most revolutionary musical genres ever to have emerged from Africa.

“I was a member of one of the very first kwaito groups ever – Trompies, in Soweto,” he says. Mahoota and Mokone own the Kalawa Jazmee record label, a firm credited with sparking the kwaito revolution. Kalawa nurtured such huge acts as Boom Shaka, Bongo Maffin and Mafikizolo.

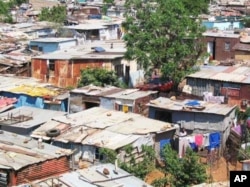

Kwaito (pronounced KWHY-toh) originated in South Africa’s impoverished townships, where vast slums are home to millions of the country’s black people. Music experts described it as a slowed down version of American house music but with strong African elements. Kwaito songs were infused with the beat of African instruments, deep bass lines, percussive loops and African voices, with lyrics often shouted.

But in recent years, kwaito has quietly moved into the background, with some critics saying it’s a spent force.

“Although kwaito remains popular, its explosion is over,” Mokone acknowledges. “In the 2000s we’ve seen a really big return to traditional South African music, and things like drum ‘n bass have become very, very popular.”

Music for a new generation

Yet Mahoota is refusing to let “pure” kwaito die. He says, “No matter what I do, and no matter what happens with kwaito in the future, I will make sure it maintains its rightful place in African music history.”

Mahoota says the genre is so important because it tells a story about a “very special” time not only in South Africa, but in all of Africa. Kwaito rose to prominence just before South Africa elected its first democratic president, Nelson Mandela.

“In the early 1990s, South African youth were still just singing revolutionary, anti-apartheid songs – really angry, depressing stuff. But then some of us artists decided to come up with something new, something to define our generation as apartheid was ending,” Mahoota explains, continuing, “We came up with something that was fresh; something that was hip, happy…something that would make people enjoy (themselves), dance, and never think about bad things that happened to them.”

M’du, a leading kwaito artist, says, “When house music got popular, people from the ghetto called it “kwaito” after the Afrikaans slang word “kwaai,” meaning those house tracks were ‘hot.’”

Crossover lyrics

Mahoota agrees that kwaito lyrics are mainly from languages spoken by black South Africans but also from local white languages. “A little bit of Afrikaans, and also a little bit of English here and there. You want everyone to understand (the lyrics). It must reach everyone,” he emphasizes.

Mahoota maintains that kwaito was the “first music genre to have crossed all language and race groups in South Africa and to have been accepted by all these diverse groups. Kwaito may have its roots in the black townships but it really is not black culture or white culture; it’s South African culture.”

In a “strange” way, he says, kwaito’s often controversial lyrics have also sometimes served to galvanize South Africa’s different race groups.

One of the first kwaito singles to become a hit across the nation, even on radio stations with mostly white listeners, was the song “‘Kaffir,” by Arthur Mafokate. “Kaffir” is a deeply racist term used extensively by white South Africans during apartheid to refer to their black compatriots. In 1995, the track’s chorus “Don’t call me kaffir! Call me baas (boss)!” sent shockwaves around the country.

Sometimes ‘shocking’ words

Mokone refers to kwaito songs like “Kaffir” as what he calls an “ironic” expression of black South Africans’ newfound self-respect. “We blacks weren’t the oppressed anymore. We were asserting ourselves; we were rebelling against the past,” he stresses.

Mokone describes white youngsters’ singing of the song at the time as “ridiculous, on the surface, but actually quite wonderful. It was an indication that young white people were also breaking the shackles of the past. What was once a hated word now became a word of liberation. It brought blacks and whites together. The new generation claimed ownership of a word created by the apartheid racists and made it something good, just through a simple song.”

Mahoota says kwaito remains ultimately “a township sound born in the ghetto” to express people’s “political frustration” and “anger” about poverty.

But he insists people “all over the world” are able to relate to the music. Mahoota says, “We go all over Africa and the response is always massive. Also, every year we go twice to perform in Europe and twice to perform in America, mostly to Africans living there. They all relate to kwaito because many of them are poor there as well, and also they feel very politically weak in these foreign lands.”

Bling, violence, money and sex

But the media, politicians, religious groups and social activists continue to criticize kwaito as “gangster” music. They maintain its proponents encourage violence in their songs.

Mahoota denies this, saying, “We use the language of the ghetto and sing about real things like crime, and not about boats sailing on the sea and love and roses.”

Mokone adds, “(The critics) hate us because we say the things that they want to say but are too afraid to say.”

Women’s groups have also often accused kwaito stars of sexism and being “anti-women.” For example, there was a public uproar in 2005 when Arthur Mafokate released his song “Sika Lekhekhe.” This Zulu phrase literally means “Cut the cake,” but its colloquial interpretation is “Have sex with me.”

Listeners and viewers complained about the track’s “sexually suggestive” content and the South African Broadcasting Corporation banned it.

Mahoota acknowledges, “I think you can say that some of the songs from kwaito might have (gone too far).” But he insists too that “many” kwaito songs “praise” and “celebrate” women. Mokone asks, “If kwaito as a genre was so anti-women, then why are some of its most successful artists females? Like Bongo Maffin’s (former) singer (Thandiswa Mazwai) and like Lebo Mathosa?”

Kwaito artists have been lambasted in the media, which accuses them of promoting the culture of “bling” materialism. Mahoota scoffs at this, describing the claim as “utter nonsense, because first of all there’s no one who’s a kwaito musician who’s rich. There’s not even one kwaito millionaire today, after all these years.”

Instead, he says, the genre has enriched “all the big foreign record companies.”

Potoko!

In his struggle to remain relevant, Mahoota recently released a track called “Potoko!” It’s proved to be immensely popular on airwaves and dance floors across Africa – and has served to announce that the former kwaito pioneer is firmly back on the music scene.

Mokone, who helped produce the song, describes it as a “war cry…. When you’re excited you say ‘Potoko!’ So when your favorite soccer team comes in and scores that goal, you say ‘Potoko!’”

For all its triumphs and “mistakes” and ongoing battle for relevance, Mahoota insists kwaito “deserves its place in the African sun” and should not be allowed to fade into obscurity. That, he maintains – and not kwaito’s dwindling sales – would be the “true tragedy.”