Humans, all mammals really, definitely got the short end of the evolutionary stick when it comes to teeth. We only have two sets, and if we lose those, well, that's why dentists will always have work.

In fact, by age 65, according to the World Health Organization, 30 percent of all people worldwide have lost all their teeth.

Now if we were bony fish, we could just regrow our lost teeth. A research team at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta, USA, is taking a closer look at the process and finds that fish and mammals may have some common genetics that could someday allow just that.

Fish replace teeth prodigiously

Cichlids are popular tropical fish that biology professor Todd Streelman studies at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta.

“Our approach is to find things that are hard to study otherwise and then target them in these animals. So in this case, Lake Malawi cichlid fishes and many other fishes regenerate their dentition throughout their entire life,” said Streelman.

Cichlids replace a mouthful of teeth every 50 days.

In a study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Streelman and his team analyzed embryotic fish cell tissue that develops into either teeth or taste buds. Streelman says they found similarities between teeth and taste buds at their earliest stages of development.

Last year, the same researchers sequenced the cichlid genome. This year, they crossed closely-related cichlids and then compared genetic differences among the second-generation hybrids.

Genetic markers for teeth and taste buds

Streelman says they discovered what appeared to be genetic switches that would tell the embryonic cells to become either teeth or taste buds.

“We could identify this because the genes that are typically positive markers of taste buds and the genes that are typically positive markers of teeth were co-expressed," he said. "They were expressed in the same places.”

The team then followed the cells through their development until they found the point in development when these cells 'decided' to become either a tooth, or a taste bud.

Teeth and taste buds start out as same tissue

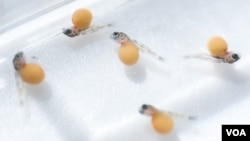

Teeth and taste buds begin in the same kind of tissue in the developing jaws of fish in their earliest stages. The scientists mapped the regions of the developing jaw specific to each. Then they manipulated the undifferentiated tissue in fish to boost tooth development over taste buds at an early stage, when the fish had eyes and a brain but were still growing jaws.

Armed with that knowledge, the genes that become teeth, and the area of the jaw where it happens, they went looking for similar genes in mammals.

It turns out that cichlids aren't the only animals that express these genes. Streelman says collaborators at Kings College London demonstrated that a few poorly studied genes in mice were also involved in the development of teeth and taste buds.

“These genes that we had identified in fishes are in fact also active in the earliest development of teeth on the jaw margin and taste buds on the tongue of mice,” he said.

Tooth regeneration coming

Streelman says the studies in fish and mice suggest that with the right signals, the tissue in humans might also be able to develop new teeth.

"The direction our research is taking, at least in human health," he said, "is to figure out how to coax the tissue to form one type of structure or the other."