IWAKI, JAPAN —

The sight of audiences applauding hula dancers and performers twirling fire knives are an indication Iwaki has bounced back - again.

The city of 300,000 people in Fukushima prefecture in northeastern Japan has been written off more than once.

Many residents first thought they were doomed after the coal mines closed in the early 1960's when Japan turned to imported oil to fuel its booming economy. But the company that ran the mines, rather than abandoning its down-on-their-luck employees, vowed to transform the community.

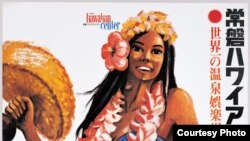

A vice president of Joban Kosan embarked on a global tour in search of ideas and returned home with a radical proposal: Iwaki would become home to a Hawaiian-themed resort - a favorite Japanese destination at a time when overseas travel was still a luxury.

Never mind that the local climate hardly matched the tropics. A dome would be built over swimming pools and water slides allowing a temperature-controlled environment.

Coal miners' daughters would be trained as hula dancers to entertain the guests.

“It was considered a totally ridiculous idea and most people were strongly opposed to the concept,” says Tomohiro Murata, sales manager of Spa Resort Hawaiians.

Business Inspiration from Pre-Feudal Japan

In a way Iwaki was returning to its ancient roots as a tourist destination. Before the mines, hot springs had attracted visitors as early as the 10th century.

The Joban Hawaiian Center was opened in January 1966 with swimming pools and hot springs baths- the latter a traditional way for Japanese to relax.

The fledgling resort gradually began to flourish, attracting up to 140,000 guests annually in the early 1970's. Then the “oil shock” of 1973 struck, literally chilling the resort's business.

Soaring energy prices and a shortage of imported oil meant the resort could no longer maintain the environment under the dome at 28 degrees Celsius. As visitor numbers dropped by 30 percent and those who did come for a swim literally shivered, the resort was derided with the nickname “Alaska Center.”

As Japan's economy recovered, the property revived and expanded (it now encompasses 300,000 square meters) and was rebranded as Spa Resort Hawaiians, becoming the largest inclusive tourism property in the Tohoku region.

Visitor numbers began to soar to more than one million per year.

In 2006, a hit movie “Hula Girl” documented Iwaki's unlikely transition from coal town to resort destination, helping to send attendance figures to unprecedented numbers.

Fukushima Meltdown Closes A Tourism Boomtown

The good fortune continued until March 11, 2011.

On that day a magnitude 9.0 earthquake hit northeastern Japan. It did only minor damage to the resort but it crippled the region's infrastructure.

Most of the 1,500 visitors at the spa took refuge in the lobby and convention hall. Amid the aftershocks the staff rounded up extra clothes for hotel guests who had been clad in the resort's ubiquitous aloha shirts and muumuu dresses.

Initially Iwaki, 180 kilometers north of Tokyo, felt lucky by comparison. The city is ten miles inland and thus was spared the tsunami, which was responsible for most of the 20,000 deaths from the disaster. But within a few days it was evident the resort again faced an existential battle. The meltdown of reactors at the Fukushima-1 nuclear power plant, 52 kilometers to the north, threw everyone into confusion, if not panic.

“We didn't know if we were safe or not,” recalls Murata. “The information put out by the government and the media kept changing and no one knew what was really happening.”

Amid the uncertainty the resort temporarily closed.

“We couldn't do anything,” says Murata.

Worried about the fate of the resort and Iwaki, he did have faith “that some day people would be able to return.”

It would be six months before operations partly resumed. During the hiatus the pipes supplying the hot springs water to the resort had to be inspected, the dome's integrity verified and the dancers' stage, damaged in a 6.0 magnitude aftershock in April, repaired.

The resort's 34 hula dancers, four fire knife performers and six musicians were sent on the road in a bus, to cheer up not only those who had evacuated their devastated communities but the rest of the country, as well.

“We were nervous. We didn't know what sort of reception we would get during the caravan,” says Mutsumi Kudo, 27, a sub-leader of the troupe.

Instead the dancers from Iwaki found the audiences, at 125 domestic venues (and one overseas trip to Seoul), trying to raise their spirits.

“They greeted us with signs saying 'Hang in There Hula Girls' and that made us very happy,” Kudo says.

The disaster transformed the troupe, according to Kudo, who joined seven years ago but first dreamed of being a hula dancer when, as a toddler, she saw a performance here.

“Before the Fukushima tragedy we took our audiences for granted. But now we are just happy to perform. It is not related to economics but rather a profound change in our hearts,” Kudo explains.

Her goal now, as part of Iwaki's third generation of dancers at the resort, is for “Fukushima to equal hula.”

Geiger Counters And Food Tests Reassure Visitors

That image has yet to take hold, as for many around the world Fukushima still equals radiation.

In Iwaki the radiation readings show a return to background levels recorded before the reactor meltdowns. It is Fukushima communities to the northeast, not south of the crippled power plant, which continue to see elevated readings. Some towns adjacent to the Fukushima-1 may be uninhabitable for many decades to come.

The resort's safety director, Takeshi Namatame, sweeps the hotel grounds daily with a Geiger counter, part of an investment of $75,000 worth of equipment purchased since last year for monitoring radiation.

“After commencing the testing and posting the results, guests from Tokyo and other metropolitan area began to feel reassured and starting coming back to our resort,” says Namatame. “They have the perception that our information is even more reliable than what government agencies release.”

Namatame has a laboratory where 15 to 20 food items that are sourced in the area are also tested daily for radiation. The water and the hot springs are checked weekly by an outside company.

This has helped Spa Resort Hawaiians fare better than Fukushima tourism in general.

"I thought it would be three years for us to recover to pre-quake levels, but it has only taken less than one year,” says resort general manager Ryuichi Sagi.

Bookings for the spa's 500 rooms are between 80 and 90 percent of pre-disaster levels for this time of year, while in the rest of Fukushima bookings are at about 50 percent.

“Older people don't seem to have much concern about the radiation,“ says sales manager Murata. “But mothers with small children still remain quite concerned about visiting Fukushima.”

Hiroki Hata from Saitama has come for a second visit with his three-year-old son.

“The situation here is not as bad as right after the disaster so I'm not worried,“ Hata says. “As long as we're not right next to the nuclear reactors there is really no concern.”

Resort Bounces Back As Symbol of Japanese Resilience

Some acknowledge they are visiting out of solidarity with hard-hit Fukushima.

“Right after the disaster I definitely wanted to support them and finally today I was able to do it,” says Sachi Konno, a visitor from Yamagata prefecture, which is also in the Tohoku region.

“I came to this resort 40 years ago but it has changed a lot since then,” she says. “It's wonderful. The attitude of the people of Fukushima gives me renewed energy."

Luring back the former regulars, as well as eventually reaching out to overseas visitors from overseas -- especially from China and South Korea - is seen as critical for the local economy.

Spa Resort Hawaiians employs 1,200 full-time and part-time staff and 90 percent are from Iwaki.

The property fully re-opened in February with additional rooms in the newly constructed 10-story Monolith Tower. The water from the natural hot springs is once again being piped into resort (including the world's largest outdoor spa water bath) and under the dome the thermometer again records a comfortable 28 degrees Celsius.

As they would say in Hawaii: just another day in paradise.

Reflecting on everything that has happened since March 11 of last year Sagi credits the people of Iwaki for doing their utmost in the face of adversity. “But we couldn't have recovered without everyone in Fukushima and support from across Japan.”

The city of 300,000 people in Fukushima prefecture in northeastern Japan has been written off more than once.

Many residents first thought they were doomed after the coal mines closed in the early 1960's when Japan turned to imported oil to fuel its booming economy. But the company that ran the mines, rather than abandoning its down-on-their-luck employees, vowed to transform the community.

A vice president of Joban Kosan embarked on a global tour in search of ideas and returned home with a radical proposal: Iwaki would become home to a Hawaiian-themed resort - a favorite Japanese destination at a time when overseas travel was still a luxury.

Never mind that the local climate hardly matched the tropics. A dome would be built over swimming pools and water slides allowing a temperature-controlled environment.

Coal miners' daughters would be trained as hula dancers to entertain the guests.

“It was considered a totally ridiculous idea and most people were strongly opposed to the concept,” says Tomohiro Murata, sales manager of Spa Resort Hawaiians.

Business Inspiration from Pre-Feudal Japan

In a way Iwaki was returning to its ancient roots as a tourist destination. Before the mines, hot springs had attracted visitors as early as the 10th century.

The Joban Hawaiian Center was opened in January 1966 with swimming pools and hot springs baths- the latter a traditional way for Japanese to relax.

The fledgling resort gradually began to flourish, attracting up to 140,000 guests annually in the early 1970's. Then the “oil shock” of 1973 struck, literally chilling the resort's business.

Soaring energy prices and a shortage of imported oil meant the resort could no longer maintain the environment under the dome at 28 degrees Celsius. As visitor numbers dropped by 30 percent and those who did come for a swim literally shivered, the resort was derided with the nickname “Alaska Center.”

As Japan's economy recovered, the property revived and expanded (it now encompasses 300,000 square meters) and was rebranded as Spa Resort Hawaiians, becoming the largest inclusive tourism property in the Tohoku region.

Visitor numbers began to soar to more than one million per year.

In 2006, a hit movie “Hula Girl” documented Iwaki's unlikely transition from coal town to resort destination, helping to send attendance figures to unprecedented numbers.

Fukushima Meltdown Closes A Tourism Boomtown

The good fortune continued until March 11, 2011.

On that day a magnitude 9.0 earthquake hit northeastern Japan. It did only minor damage to the resort but it crippled the region's infrastructure.

Most of the 1,500 visitors at the spa took refuge in the lobby and convention hall. Amid the aftershocks the staff rounded up extra clothes for hotel guests who had been clad in the resort's ubiquitous aloha shirts and muumuu dresses.

Initially Iwaki, 180 kilometers north of Tokyo, felt lucky by comparison. The city is ten miles inland and thus was spared the tsunami, which was responsible for most of the 20,000 deaths from the disaster. But within a few days it was evident the resort again faced an existential battle. The meltdown of reactors at the Fukushima-1 nuclear power plant, 52 kilometers to the north, threw everyone into confusion, if not panic.

“We didn't know if we were safe or not,” recalls Murata. “The information put out by the government and the media kept changing and no one knew what was really happening.”

Amid the uncertainty the resort temporarily closed.

“We couldn't do anything,” says Murata.

Worried about the fate of the resort and Iwaki, he did have faith “that some day people would be able to return.”

It would be six months before operations partly resumed. During the hiatus the pipes supplying the hot springs water to the resort had to be inspected, the dome's integrity verified and the dancers' stage, damaged in a 6.0 magnitude aftershock in April, repaired.

The resort's 34 hula dancers, four fire knife performers and six musicians were sent on the road in a bus, to cheer up not only those who had evacuated their devastated communities but the rest of the country, as well.

“We were nervous. We didn't know what sort of reception we would get during the caravan,” says Mutsumi Kudo, 27, a sub-leader of the troupe.

Instead the dancers from Iwaki found the audiences, at 125 domestic venues (and one overseas trip to Seoul), trying to raise their spirits.

“They greeted us with signs saying 'Hang in There Hula Girls' and that made us very happy,” Kudo says.

The disaster transformed the troupe, according to Kudo, who joined seven years ago but first dreamed of being a hula dancer when, as a toddler, she saw a performance here.

“Before the Fukushima tragedy we took our audiences for granted. But now we are just happy to perform. It is not related to economics but rather a profound change in our hearts,” Kudo explains.

Her goal now, as part of Iwaki's third generation of dancers at the resort, is for “Fukushima to equal hula.”

Geiger Counters And Food Tests Reassure Visitors

That image has yet to take hold, as for many around the world Fukushima still equals radiation.

In Iwaki the radiation readings show a return to background levels recorded before the reactor meltdowns. It is Fukushima communities to the northeast, not south of the crippled power plant, which continue to see elevated readings. Some towns adjacent to the Fukushima-1 may be uninhabitable for many decades to come.

The resort's safety director, Takeshi Namatame, sweeps the hotel grounds daily with a Geiger counter, part of an investment of $75,000 worth of equipment purchased since last year for monitoring radiation.

“After commencing the testing and posting the results, guests from Tokyo and other metropolitan area began to feel reassured and starting coming back to our resort,” says Namatame. “They have the perception that our information is even more reliable than what government agencies release.”

Namatame has a laboratory where 15 to 20 food items that are sourced in the area are also tested daily for radiation. The water and the hot springs are checked weekly by an outside company.

This has helped Spa Resort Hawaiians fare better than Fukushima tourism in general.

"I thought it would be three years for us to recover to pre-quake levels, but it has only taken less than one year,” says resort general manager Ryuichi Sagi.

Bookings for the spa's 500 rooms are between 80 and 90 percent of pre-disaster levels for this time of year, while in the rest of Fukushima bookings are at about 50 percent.

“Older people don't seem to have much concern about the radiation,“ says sales manager Murata. “But mothers with small children still remain quite concerned about visiting Fukushima.”

Hiroki Hata from Saitama has come for a second visit with his three-year-old son.

“The situation here is not as bad as right after the disaster so I'm not worried,“ Hata says. “As long as we're not right next to the nuclear reactors there is really no concern.”

Resort Bounces Back As Symbol of Japanese Resilience

Some acknowledge they are visiting out of solidarity with hard-hit Fukushima.

“Right after the disaster I definitely wanted to support them and finally today I was able to do it,” says Sachi Konno, a visitor from Yamagata prefecture, which is also in the Tohoku region.

“I came to this resort 40 years ago but it has changed a lot since then,” she says. “It's wonderful. The attitude of the people of Fukushima gives me renewed energy."

Luring back the former regulars, as well as eventually reaching out to overseas visitors from overseas -- especially from China and South Korea - is seen as critical for the local economy.

Spa Resort Hawaiians employs 1,200 full-time and part-time staff and 90 percent are from Iwaki.

The property fully re-opened in February with additional rooms in the newly constructed 10-story Monolith Tower. The water from the natural hot springs is once again being piped into resort (including the world's largest outdoor spa water bath) and under the dome the thermometer again records a comfortable 28 degrees Celsius.

As they would say in Hawaii: just another day in paradise.

Reflecting on everything that has happened since March 11 of last year Sagi credits the people of Iwaki for doing their utmost in the face of adversity. “But we couldn't have recovered without everyone in Fukushima and support from across Japan.”