This is Part 1 of a 5-part series: Honoring Africa’s Traditional Music

Continue to Parts 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5

In 1966, Prime Minister Milton Obote imposed a new constitution on Uganda and abolished the ceremonial presidency held by Kabaka (King) Edward Mutesa II. Obote declared himself executive president and ordered the army to attack the king’s hilltop palace that overlooked Kampala.

Soldiers led by then Colonel Idi Amin duly obliged. They killed some of Mutesa’s family and staff, but he escaped and went into exile in England, where he died a few years later.

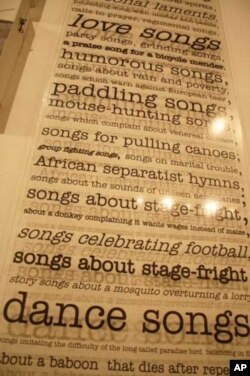

As well as ending the Buganda monarchy, the palace siege destroyed a significant part of Uganda’s cultural, and specifically musical, history. For centuries, Buganda rulers had employed musicians to entertain them and their guests and to perform at royal court proceedings. According to historians, these musicians created some of Africa’s most important music.

But Amin’s forces killed most of them. Those who survived fled Uganda. The soldiers also destroyed almost all of the ancient royal musical instruments, such as drums, lutes and lyres.

“That (Buganda royal) music is completely dead now…in the sense that there’s no one left to play it, no one left to teach it to modern generations of Ugandans,” said South African ethnomusicologist Andrew Tracey. But, he added, “The sound of it lives, as a result of my father’s work.”

The music of kings saved

Andrew’s father, pioneer ethnomusicologist Hugh Tracey, spent about 50 years until his death in 1977 traveling from his base in South Africa through sub-Saharan Africa to record and preserve the region’s indigenous music.

In 1950, he spent a significant time at the palace of the Buganda king, taping the music made there. His is the only record that remains of this unique music.

“Through his mission, my father undoubtedly saved a lot of African music from complete destruction,” Andrew told VOA. Some of Hugh Tracey’s remarkable recordings of music that would otherwise have been lost forever have now been made available on CD. The sounds he collected using primitive equipment have been re-mastered by the International Library of African Music in South Africa.

One of these CDs contains music Hugh Tracey recorded in 1952 at the court of the Tutsi mwami (king) in Rwanda. When the country became independent of Belgium in 1961, the monarchy was scrapped and the music it had fostered vanished. Again because of his father’s foresight, said Andrew, the “powerful and sophisticated” sound of Rwanda’s royal court survived.

“There are expatriate groups of Tutsis who actually try and keep that music going and they are able to make use of (my father’s) recordings to try and reconstruct it,” Andrew explained.

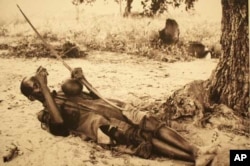

Also in the early 1950s, Hugh Tracey was present when Mbuti pygmies emerged from the Ituri rainforest in what’s now the Democratic Republic of Congo to barter with their Bantu neighbors. The occasion was celebrated with music made by all involved, and Hugh Tracey recorded it.

Another CD offers a selection of performances from peoples who have long since disappeared from Africa. On one track, listeners are able to hear 600 men and women of the Chagga ethnic group chanting on the slopes of Mount Meru in Kenya.

‘Legendary’ George Sibanda

Through his recordings, Hugh Tracey also documented “musical revolutions” that happened in the rapidly urbanizing Africa of the 1950s and 1960s, said Andrew. In some cities, and especially in the mining towns of Congo and southern Africa, the guitar at this time became an important status symbol for some entertainers.

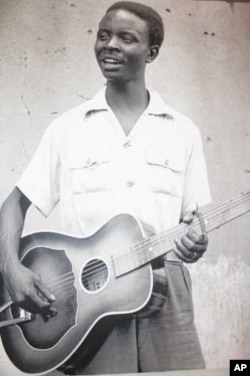

Andrew said two of the “most amazing” artists that Hugh Tracey brought to the attention of radio stations throughout Africa, and other parts of the world were singer-songwriter guitarists Jean Bosco Mwenda of Congo and George Sibanda of Zimbabwe.

Andrew reflected, “My father first met George in 1948 and immediately noticed that he could pick a guitar like no one else. He also had a very good, warm voice. He wrote fantastic songs and most of his music had that feel-good factor that uplifted anyone who listened, which made him very popular.”

Musicologists have branded Sibanda sub-Saharan Africa’s “first radio star.” He had hit songs all over the continent, even though listeners couldn’t understand his lyrics because he sang in his native Ndebele. Some of his songs were, however, translated and in the 1960s and 1970s recorded by famous American folk artists Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and Arlo Guthrie, and by blues icon Taj Mahal.

”George was truly a legendary artist,” said Andrew. But by the end of the 1950s, the legend was dead…succumbing to the ravages of alcohol abuse. Thanks to Hugh Tracey’s recordings, though, Sibanda’s music endures.

‘Genius’ of Jean Bosco Mwenda

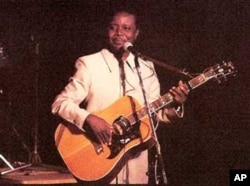

Andrew first heard of Jean Bosco Mwenda in the early 1950s while studying in England. “Dad used to keep in touch by sending me some of his latest recordings. One of them was by this guy, a young street guitarist from southern Congo named Jean Bosco Mwenda. The musical genius of this man hit me right between the eyes,” he remembered.

Andrew said Mwenda had “fantastic technique and compositional ability and everyone loved his music. I got a guitar around about that time, at school, and I learnt to play the guitar by learning Bosco’s music. I’ve been playing it ever since.”

Mwenda was a pioneer of Congolese finger-style acoustic guitar music. Hugh Tracey championed him, and he became popular across Africa, but mainly in east Africa. In the late 1950s and early 1960s Mwenda was based in the Kenyan capital, Nairobi, where he performed regularly on radio and, said Andrew, influenced a lot of Kenyan guitarists.

In 1988, Andrew Tracey brought Mwenda to South Africa, where he gave a number of acclaimed performances. “He was a much older man by then but still playing the same tunes he’d played in his boyhood – and more, of course. That was a great experience, hearing him live,” Andrew recalled.

While in South Africa, Mwenda cut a few songs in a studio in Cape Town. They were his final recordings. He died in a road accident in Zambia in 1990, aged 60.

‘Misunderstood’ legacy

As well as some of Hugh Tracey’s recordings now being available on CD, the International Library of African Music has archived the sound he collected during his field visits.

“What we had to do is to match up the field recordings with the field cards and create a catalogue, so what we now have is over 20,000 sound items from all the various recordings that Hugh Tracey made,” said library director and American musicologist, Prof. Diane Thram.

The archive is now available online on the Library’s website (www.ilam.co.za).

It gives people around the world has access to Hugh Tracey’s recordings through MP3 sound files and metadata documents that contain information about each piece of music.

“It’s all pointed at educating people about African music, educating people about Hugh Tracey’s legacy, dispelling some of the misconstrued notions about Hugh Tracey which have somehow developed over the years,” said Thram.

Explaining further, Andrew told VOA, “There were stories that we made fortunes out of recording and selling African music. Now while one has heard of that happening, that’s not what we did. Our motivation was to preserve Africa’s musical culture, and you can see that today in the Library. We always survived on grants from organizations that saw value in our work and also saw value in African music. That money was used to fund our work and not for personal enrichment.”

But despite his and his father’s dedication to safeguarding Africa’s musical heritage since the 1920s, Andrew acknowledged that he sometimes asked himself, “Is it really important to try and keep something ancient alive and known?”

His answer, he said, was always the same: “I believe deep down that it is important – if only to reduce the sense of being without history that many Africans (mistakenly) have.”

And when Andrew listened to recordings made by himself and his father, he said, all doubts about their legacy were swamped by the “sheer beauty” of Africa’s musical past.