Earlier this year in Hakha, the capital of Myanmar’s mountainous and remote Chin state, days of heavy rain saturated the ground beneath the hilltop town.

On the afternoon of July 28, Teng Mawng, 52, felt the floor of his home rumble as a large section of the earth above the town became dislodged, sending the contents of a lake, along with a mass of dirt and rock, surging through his neighborhood.

“The water rushed past and took away all the land,” he said. “Me and all my neighbors had to move out.”

In what locals say was the worst natural disaster in living memory, towns and villages across Chin state were ravaged by landslides. According to data collected from local relief groups, almost 20,000 people have been displaced and a total of nearly 55,000 people were affected by the disaster.

Months after the landslides, the main roads in the capital Hakha have largely been cleared by bulldozers, but the true recovery has barely started.

Dangerous ground

The landslide has raised concerns about the long term stability of parts of Hakha itself. An assessment map included in a Myanmar government report marks a residential section of the town as a “high risk zone [needs relocation].” Other areas of the town are denoted: “urgent mitigation needed.” A project is underway to relocate more than 4,000 displaced members of the town’s population of about 30,000.

In the neighboring township Falam, 23 of the area’s 180 villages will have to relocated as living there has become untenable, according to Thawng Bik, a local Baptist pastor and the secretary of the Chin Relief Committee-Falam.

“People here rely on agriculture and livestock. The landslide mostly affects farmland, so that’s affecting people’s economic situation,” Thawng Bik said. “It’s really bad for some villages that still can’t be reached by aid or support. There are some villages located beyond rivers, where the bridge that crossed the river has collapsed, so they are still in real trouble.”

The situation is worsened by long-term central government neglect of Chin state, home to the mostly Christian Chin ethnic minority, said Flora Bawi Nei Mawi, program officer at the Chin Human Rights Organization. That means the state lacks vital infrastructure, with only a handful of paved roads linking the major towns, and no airport.

“I’d like to stress the lack of infrastructure. That makes us more vulnerable for the natural disasters,” she said.

Aid trickles into remote countryside

Much of the aid sent to help Chin state had to pass through other areas of Myanmar affected by flooding this year, so supplies were often depleted by the time they reached Chin communities in the mountains, said Flora Bawi Nei Mawi.

“And when it comes to reconstruction, the lack of infrastructure makes the process more difficult,” said Mawi.

The Asian Development Bank’s principle country specialist for Myanmar, Peter Brimble, agreed that Chin state’s geography and lack of infrastructure were hampering recovery efforts.

“It’s tough to get in and it’s tough to get out, and that causes a challenge for agencies like ours, working to get people in, working to mobilize local communities, and actually to get materials in and out to rebuild [damaged] assets,” he said.

The ADB is preparing a $12 million grant-funded project to help people impacted by the landslides in Chin state. The bank will provide funds to local communities to reconstruct vital routes connecting villages to the major roads, and for other recovery works like rebuilding terraces that allow farmers to grow rice on steep hills.

“In a geographic area that is isolated like that, one of the approaches that we explore carefully is to utilize the resources and people in community-based organizations down on the ground,” Brimble said.

As well as funds coming from international donors, the Myanmar government is spending about $3 million to relocate Hakha residents. With the help of the Japanese international aid agency, JICA, the government has begun a project to restore the road connecting Hakha to the nearest major city, Kale.

Uncertain future

Activists, however, say local communities have not been properly consulted on government-led recovery efforts so far, which have been directed by central government agencies, with contracts allegedly awarded to companies closely linked to favored officials. Additionally, there are concerns that a rushed reconstruction will leave residents with low-quality infrastructure that will not be able to resist the harsh weather conditions of Chin state for more than a few years.

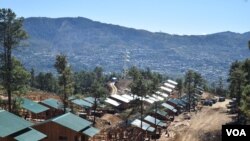

On a hillside just outside of Hakha, more than 700 new homes are under construction for displaced residents. Inspecting one of the unfinished houses, retired carpenter Teng Mawng said he had some complaints about the quality of the structure. “This place is also quite far from town,” he said, “but we will have to get used to it.”

Those waiting to move in are currently housed in temporary camps. While keen to move into permanent homes before the weather grows colder this month, they say they are concerned that no firm plans have been presented to build a school or a clinic in the new settlement. “The house is free, so we have to accept it,” said Teng Mawng.