The asteroid that triggered a mass extinction and the demise of the dinosaurs 66 million years ago gave rise to a modern age of fishes, according to a new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The ocean was a different place at the time of the massive die off. Sharks and octopus-like creatures were big players, but paleobiologist Elizabeth Sibert said there were large marine reptiles and fish as well, “Except the fish weren’t very dominant.”

Explosion in fish population

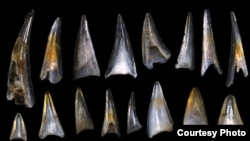

The University of California San Diego graduate student worked with co-author professor Richard Norris at UC San Diego and Scripps Institution of Oceanography. The two compared micro-fossil fish teeth and shark scales, in sediment cores that dated before and after the mass extinction.

“Basically the deeper down you get, the older you get,” Sibert explained. “So we looked at sediments from 75 million years ago to about 45 million years ago, looking every 200,000 years in some cases and 10,000 years in other cases.”

Prior to the mass die-off, the ratio of fish to shark was stable, but Sibert said that changed dramatically when the asteroid hit.

“We see that instead of having about equal number of shark fossils and fish fossils, we see that the fish fossils more than double and that trend continues while the shark fossils stay approximately the same,” she said.

New niches open

The study suggests that the extinction event killed many animals at both the top and bottom of the food chain, opening niches to the ray-finned fish, which today represent nearly all fish species. Norris was surprised with the speed at which the fish multiplied, suggesting that they “were released from predation or competition by the extinction of other groups of marine life.”

“And they radiated into all these newly vacated spots, and possibly some new things that wouldn’t have existed at all if the extinction hadn’t happened,” Sibert added.

Ninety-nine percent of all fish species in the world - from goldfish to tuna and salmon - are classified as ray-finned fish. They have boney skeletons and teeth that are well preserved in the ocean mud.

The next step for the researchers is to return to the micro-fossil record to find out how the fish responded to other stresses in the ocean, like global warming.