NEW DELHI —

In a landmark judgment, India’s Supreme Court on Monday rejected a patent for a cancer drug produced by a Swiss pharmaceutical company. The ruling is seen as a huge boost for availability of affordable drugs to treat deadly diseases, but a big blow to Western pharmaceutical companies fighting for more stringent patent protection in India, a hub for generic drugs.

The seven-year legal battle between Novartis and Indian authorities drew to a close Monday when the court said that the cancer-fighting drug Glivec did not satisfy the test of “novelty or inventiveness" required by Indian law to justify a patent.

Novartis sought a patent calling the updated version of Glivec a huge advance on the earlier drug. India, however, says Glivec is not a new drug but an amended version of a known medicine. Glivec is used to treat leukemia and is patented by many countries.

A lawyer for the Cancer Aid Patients Association in New Delhi, Anand Grover, said India’s patent law is stricter than in many countries and only grants patents for genuine inventions. “It does not allow new forms of known substances to be patented unless they are significantly more efficacious,” Grover stated.

The case is widely seen as a high-stakes battle between Western pharmaceutical companies that want a stricter patent regime in India and global health care activists fighting to safeguard the availability of affordable drugs produced by India’s thriving generic industry.

Health care activists are jubilant with the supreme court ruling. Doctors Without Borders says it protects public health and will ensure that millions of people across the globe are not cut off from a supply of affordable drugs used to treat deadly diseases like AIDS, tuberculosis and cancer.

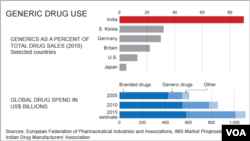

“India produces 80 percent of the generic medicines that are used in lower and middle income countries," said Jennifer Kohn, medical director at Doctors Without Borders in Geneva. "In order for us to be truly to be able to access important life saving medicines to treat our patients, we need access to these lower cost generic versions.”

The price difference between generic and branded drugs is huge - a month’s dosage of branded Glivec, for example, costs about $ 2,500 compared to about $175 for generics in India.

Drug companies are discouraged by the ruling. Novartis has expressed concerns about India’s “growing non-recognition of intellectual property." Ranjit Shahani heads the India operations of the Swiss company.

“It is not very encouraging and shows that the ecosystem to encourage innovation does not exist in India…we have seen that investments in R and D [research and development] centers since 2005, since we have had a patent law in place, all, every single one without exception has gone to China," Shahani explained. "So this gravitation of investment needs to come to India.”

The court’s ruling is also a setback to other multinationals involved in patent disputes in India. India has not hesitated in allowing local production of expensive medicines. Last year, it gave the go-ahead to a local manufacturer to make a generic version of a cancer drug made by Bayer, citing the need to make medicines available to people at affordable costs.

Multinational drug companies see the Indian law as a way of circumventing patent rights and argue inadequate patent protection will discourage innovators.

The seven-year legal battle between Novartis and Indian authorities drew to a close Monday when the court said that the cancer-fighting drug Glivec did not satisfy the test of “novelty or inventiveness" required by Indian law to justify a patent.

Novartis sought a patent calling the updated version of Glivec a huge advance on the earlier drug. India, however, says Glivec is not a new drug but an amended version of a known medicine. Glivec is used to treat leukemia and is patented by many countries.

A lawyer for the Cancer Aid Patients Association in New Delhi, Anand Grover, said India’s patent law is stricter than in many countries and only grants patents for genuine inventions. “It does not allow new forms of known substances to be patented unless they are significantly more efficacious,” Grover stated.

The case is widely seen as a high-stakes battle between Western pharmaceutical companies that want a stricter patent regime in India and global health care activists fighting to safeguard the availability of affordable drugs produced by India’s thriving generic industry.

Health care activists are jubilant with the supreme court ruling. Doctors Without Borders says it protects public health and will ensure that millions of people across the globe are not cut off from a supply of affordable drugs used to treat deadly diseases like AIDS, tuberculosis and cancer.

“India produces 80 percent of the generic medicines that are used in lower and middle income countries," said Jennifer Kohn, medical director at Doctors Without Borders in Geneva. "In order for us to be truly to be able to access important life saving medicines to treat our patients, we need access to these lower cost generic versions.”

The price difference between generic and branded drugs is huge - a month’s dosage of branded Glivec, for example, costs about $ 2,500 compared to about $175 for generics in India.

Drug companies are discouraged by the ruling. Novartis has expressed concerns about India’s “growing non-recognition of intellectual property." Ranjit Shahani heads the India operations of the Swiss company.

“It is not very encouraging and shows that the ecosystem to encourage innovation does not exist in India…we have seen that investments in R and D [research and development] centers since 2005, since we have had a patent law in place, all, every single one without exception has gone to China," Shahani explained. "So this gravitation of investment needs to come to India.”

The court’s ruling is also a setback to other multinationals involved in patent disputes in India. India has not hesitated in allowing local production of expensive medicines. Last year, it gave the go-ahead to a local manufacturer to make a generic version of a cancer drug made by Bayer, citing the need to make medicines available to people at affordable costs.

Multinational drug companies see the Indian law as a way of circumventing patent rights and argue inadequate patent protection will discourage innovators.