To get kids and moms to wash their hands, aim for their hearts.

That is the lesson from a new study that focused on emotional appeals over hard facts to encourage handwashing, one of the best and most underutilized ways to prevent disease.

Diarrheal and and respiratory diseases are the two leading causes of child death worldwide. Research shows that just washing hands with soap and water before eating and after using the bathroom can cut rates of some of these illnesses by a third.

Everyone says it, no one does it

But handwashing rates are low worldwide, despite years of public education campaigns.

At the start of this study, published in the journal The Lancet Global Health, villagers in Andhra Pradesh, India, washed less than three percent of the time.

“If you ask people, should they wash their hands with soap? Almost everybody says, of course they should,” said Hygiene Center chief Val Curtis at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. “The problem is, everyone says it, but hardly anybody actually does it.”

Emotional advertising

But rather than telling people that washing their hands is good for them, Curtis and her colleagues took a tip from the world of advertising.

“Nobody sells fizzy drinks on the fact that it’s good nutrition,” she said. “They’re all sold on emotional benefits.”

So they laid down ground rules for messaging: “No diarrhea, no death and no doctors," and developed a handwashing campaign that used emotional drivers like disgust and the desire to nurture.

Gross lesson

Curtis describes herself as a “disgustologist.” It’s a more powerful motivator than information, she adds.

Children watched a skit featuring a character who makes sweets out of mud and snot, and never washes his hands. The kids recoiled in mock horror when he offered them his treats.

“The emotion would be what taught them about dirty hands, not lecturing them,” Curtis said.

The campaign took a different tack with mothers.

Pass the hankies

“Mothers care deeply about teaching their child good manners,” she noted. “And handwashing is part of good manners.”

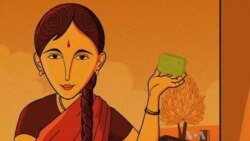

So a local ad agency worked with them to produce “SuperAmma,” or “SuperMom,” a cartoon character who is the hardworking, nurturing mother every mom aspires to be.

SuperAmma teaches her son to always be polite, be clean, comb his hair, and wash his hands.

In the cartoon’s final, tearjerking montage, all her hard work has paid off: her son has grown up to be a doctor. It closes with the two of them in a loving embrace.

“We had to pass the hankies around at the screenings in the villages,” Curtis said.

"A step in the right direction"

It worked. Handwashing rates went from one or two percent at the start of the study to nearly a third a year after the campaign ended.

It is not enough, Curtis said, but it is “a step in the right direction,” and it suggests a way forward for future campaigns.

Emotions were probably not the only factor at work, notes international health professor Elli Leontsini at Johns Hopkins University. They likely helped to change people’s behavior at the start.

But other parts of the campaign may have been more important for sustaining it. For example, villagers made a public pledge to wash their hands with soap before eating and after using the bathroom. That creates peer pressure and changes community expectations.

“It’s a whole package, not just emotions,” Leontsini said.

Expect more public health campaigns to get emotional. Curtis plans to bring her approach to efforts aimed at raising breastfeeding rates and improving food preparation habits.

That is the lesson from a new study that focused on emotional appeals over hard facts to encourage handwashing, one of the best and most underutilized ways to prevent disease.

Diarrheal and and respiratory diseases are the two leading causes of child death worldwide. Research shows that just washing hands with soap and water before eating and after using the bathroom can cut rates of some of these illnesses by a third.

Everyone says it, no one does it

But handwashing rates are low worldwide, despite years of public education campaigns.

At the start of this study, published in the journal The Lancet Global Health, villagers in Andhra Pradesh, India, washed less than three percent of the time.

“If you ask people, should they wash their hands with soap? Almost everybody says, of course they should,” said Hygiene Center chief Val Curtis at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. “The problem is, everyone says it, but hardly anybody actually does it.”

Emotional advertising

But rather than telling people that washing their hands is good for them, Curtis and her colleagues took a tip from the world of advertising.

“Nobody sells fizzy drinks on the fact that it’s good nutrition,” she said. “They’re all sold on emotional benefits.”

So they laid down ground rules for messaging: “No diarrhea, no death and no doctors," and developed a handwashing campaign that used emotional drivers like disgust and the desire to nurture.

Gross lesson

Curtis describes herself as a “disgustologist.” It’s a more powerful motivator than information, she adds.

Children watched a skit featuring a character who makes sweets out of mud and snot, and never washes his hands. The kids recoiled in mock horror when he offered them his treats.

“The emotion would be what taught them about dirty hands, not lecturing them,” Curtis said.

The campaign took a different tack with mothers.

Pass the hankies

“Mothers care deeply about teaching their child good manners,” she noted. “And handwashing is part of good manners.”

So a local ad agency worked with them to produce “SuperAmma,” or “SuperMom,” a cartoon character who is the hardworking, nurturing mother every mom aspires to be.

SuperAmma teaches her son to always be polite, be clean, comb his hair, and wash his hands.

In the cartoon’s final, tearjerking montage, all her hard work has paid off: her son has grown up to be a doctor. It closes with the two of them in a loving embrace.

“We had to pass the hankies around at the screenings in the villages,” Curtis said.

"A step in the right direction"

It worked. Handwashing rates went from one or two percent at the start of the study to nearly a third a year after the campaign ended.

It is not enough, Curtis said, but it is “a step in the right direction,” and it suggests a way forward for future campaigns.

Emotions were probably not the only factor at work, notes international health professor Elli Leontsini at Johns Hopkins University. They likely helped to change people’s behavior at the start.

But other parts of the campaign may have been more important for sustaining it. For example, villagers made a public pledge to wash their hands with soap before eating and after using the bathroom. That creates peer pressure and changes community expectations.

“It’s a whole package, not just emotions,” Leontsini said.

Expect more public health campaigns to get emotional. Curtis plans to bring her approach to efforts aimed at raising breastfeeding rates and improving food preparation habits.