Photographer John Rowe discovered a deeply held secret on visits to the Omo River Valley in southwestern Ethiopia, a place of traditional culture and spectacular beauty. Children regarded as cursed, or "mingi," were thought to be responsible for misfortune and were killed.

"The reason why people get sick, the reason why there's drought, the reason why there's famine, is because of ‘mingi,’” Rowe explained.

If children's teeth first appear on the upper gum instead of the bottom gum, or if they are born out of wedlock, disabled, or are twins, they are ritualistically murdered.

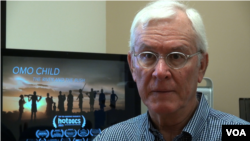

Rowe learned of the practice from Lale Labuko, his guide on his photographic journeys, and produced a documentary film about the practice called Omo Child.

At age 15, Labuko saw a two-year-old child being drowned in the river and learned from his mother that he had also had two sisters who were killed before he was born.

One woman in the film recounts losing 15 children at birth, all declared "mingi" and snatched by village elders to be fed to crocodiles.

"I said, I want to stop these things," Labuko recalls in the film.

Labuko was the first member of his village to receive an education at a missionary school. He asked Rowe to help him end the killings as he first persuaded young people, then the families of his village and tribal elders.

Filming spanned five years and wasn't always easy, said Rowe's son Tyler, the director of cinematography. A few people were forthright, including some who had killed their children, but others denied the practice.

They insisted that "it doesn't happen here," recalled Tyler. "’We stopped it a long time ago,’ they said. ‘It only happens off in this far village ... those backward people. It's not us.’"

Through Labuko's efforts, however, the practice came to light in open discussion, and his Karo tribe agreed to ban "mingi" in 2012, as Rowe documented the effort in his film.

Omo Child was recently shown in Los Angeles at the Skirball Cultural Center, a Jewish institution, as part of a series featuring winners of the Social Impact Media Awards.

Audience members were given a packet to show how they can get involved with non-profit organizations to help solve social problems, from sex trafficking to the exploitation of workers in the fashion industry.

"We feel so connected to the world now via the internet," said Marie Bobin, who coordinates the series, "yet there are still stories that are unknown to us."

She says film has the power to tell those stories.

A charity set up by Labuko and his wife has saved more than 40 "mingi" children at a group home in Jinka, Ethiopia.

The Ethiopian government has banned the practice, yet "there are two other tribes that continue to practice ‘mingi,'" said the filmmaker.

But because of his film, more people know about the practice and the efforts of a Karo man to stop it.