The Zika virus rarely causes problems for the people who get it. Eighty percent don't show any symptoms, others might have a rash or a slight fever.

The disease seems insignificant, but it also seems to be having a devastating effect on babies whose mothers are infected with the virus.

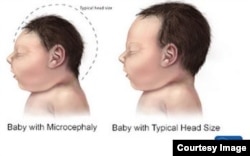

The Zika virus erupted in Brazil last May, and now more than 4,000 babies born there are suspected of having microcephaly, an abnormally small head.

The link between Zika and microcephaly has not been proven, but the World Health Organization says that until scientists come up with a better explanation, they believe the Zika virus is the cause.

CDC information

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says the condition is unusual — that between two and 12 babies out of every 10,000 live births in the U.S. have microcephaly.

The CDC website shows an image of a baby with a small head. The dashes show how big a normal baby's head should be.

The CDC says microcephaly can occur when a baby's brain doesn't develop properly during pregnancy or has stopped growing after birth.

Degrees of disease

Babies with this disorder can have a range of other problems, depending on the severity of the condition.

Microcephaly has been linked to problems with speech, standing and walking, balance, hearing and vision.

But, in a Skype interview, Dr. Edward McCabe from the March of Dimes said it doesn't always have devastating consequences.

"Ten to 15 percent of American babies with microcephaly are completely normal,” he said. “The concern is how these babies are going to develop as they get older."

The key is to get the babies properly evaluated by the appropriate professionals.

"That will usually include a neurologist to see what their assessment is, what they conclude caused this microcephaly, doing an ultrasound of the brain, doing an MRI of the head, but the important thing is to follow the baby clinically, and it doesn't hurt to have early intervention," McCabe said.

Intervention might include physical or speech therapy.

McCabe also said not every baby will have the same outcome.

"Our knowledge of microcephaly prior to the Zika virus association is that there is a spectrum that stretches from normal, even high intelligence, through the spectrum in terms of developmental delay," he said.

Unknowns frustrating

Not much is known about Zika, including when it is most likely to cause a fetal brain to stop developing, assuming that is true. But doctors suspect the most dangerous time for a woman to acquire the Zika virus is in the first trimester of pregnancy.

"From a developmental perspective, the first three months of a pregnancy is when the brain is most actively developing its structure, and what will be important to later function," McCabe said.

Like other scientists, McCabe is frustrated by the lack of scientific information available on the Zika virus and its link to microcephaly.

"We need more data," he said.

Until more is known, doctors are telling pregnant women not to travel to regions that have the Zika virus.

Pregnant women in South and Central America and the Caribbean, and those who may become pregnant, are told to wear long-sleeved shirts, long pants and hats, and use an insect repellent with DEET on any uncovered skin.

And that, in itself, is concerning.

The CDC says DEET is safe for pregnant women to use, but it cautions against spraying clothes.

"You don't want the prolonged exposure of having DEET on your clothing,” McCabe said, “so by wearing the long-sleeved shirts, long pants, the hat, you are decreasing the area of your skin that needs to be exposed to DEET and, therefore, decreasing your exposure."