"They were cut off from their families and it was very difficult," says Line Ouellet, telling the story of many aboriginal people in Quebec and elsewhere in Canada who were confined to reservations as recently as 50 years ago. Their children were sent to convents for their education, depriving them of access to their native language and culture.

Ouellet is the director of Quebec City's National Museum of Fine Arts, which has just opened a new pavilion to showcase 400 contemporary works by Quebec artists, including native artist Nadia Myre, whose work The Scar she is describing. In small beige canvases, Myre has collected the memories of her people and the breaking up of families. Each person stitched an image onto a canvas, which was then displayed in a grouping with others, each telling an individual tale of loss in a story with hundreds of chapters.

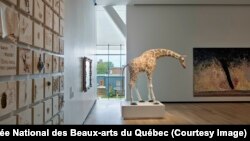

The work is housed in the museum's 15,000-square-meter, three-level pavilion constructed of glass and steel and cement, with transparency, translucency, and literal windows in walls to connect the galleries with each other and museum-goers with the world around them. Even a staircase leading from the third floor to the second is structured on the side of the building and encased in glass, so one can see the rolling fields and the river that surround the museum. At night, the museum looks like a box full of light.

Bridging green space, urban life

The pavilion's glass front opens onto one of Quebec's grandest avenues, connecting the street with the museum. It offers an alternative to the old entrance, which sits 500 meters back in the city's National Battlefields park. "Winter is long here, almost six months," says Ouellet. "The intention was to be in the city, to have an urban facade," which will allow visitors to duck into the building from the street, rather than trudging into the park through the snow.

The Pierre Lassonde pavilion, named for the gold-mining magnate who heads the museum's board of directors, looks like three boxes set on top of each other, with the lowest level facing the St. Lawrence River and the highest level facing the street and the historic city of Quebec beyond. Outdoor terraces connect visitors with the natural world outside the museum. Interior spaces connect them with the stories told by Quebecois art.

Myre's piece is part of the museum's collection of contemporary art (created in 1960 or later) by the native Inuit people, who were traditionally nomadic. Earlier pieces would have been small, Ouellet says, so as to be easily carried from one place to another. Today's art includes large, delicate pieces - intricate carvings of wood and bone, and smooth, graceful stone sculptures depicting various forms of wildlife.

The new space available in the museum, which also includes a former church and a former prison, has made it possible to display 34 art installations, three-dimensional creations that can surround the viewer, offering an immersive experience and, in many cases, taking up a lot of space. One smaller piece, Yannick Pouliot's Le Courtesan, looks from the outside like a packing crate, perhaps left over from the recent construction. But when the viewer steps inside and shuts the door, a light pops on, music springs to life, and one finds oneself in a tiny, elegantly decorated octagon that looks and sounds like the 18th century. It is French history in a box.

Other spaces inside the museum house displays of Quebec-made ceramics (a deliberate choice, as ceramics will not fade when exposed to sunlight) and industrial design - artfully designed everyday objects such as chairs, tools, and tableware.

French language and culture

The museum, like Quebec, is focused on preserving its unique heritage in a French-speaking province of a nation that is part of the British Commonwealth. Quebecois are known for their endless battles to preserve their Francophone culture and even to break off from the rest of Canada entirely. On Friday, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, in town to speak at the museum's opening ceremony, was booed for speaking English for 17 seconds - about Britain's vote to exit the European Union - before he switched to French.

Fittingly, the incident took place on the grounds of the battlefield where British and French troops battled for sovereignty over Quebec. Britain won the battle, but Quebecois have never fully capitulated.

To be fair, Trudeau also made his gaffe on a day when patriotism was running high. June 24 is Quebec's fete nationale, or national holiday, celebrated with parades, music, food, and parties that take full advantage of the early summer weather. It seemed the perfect day to invite people into a new, light-filled house of Quebecois culture.