Scientists have discovered the key to rehabilitating damaged salivary glands, promising relief for head and neck cancer patients whose glands are destroyed by radiation therapy.

Living with non-functioning salivary glands has been a necessary evil for head and neck cancer patients who must undergo lengthy programs of radiation therapy.

The side effect, chronic dry mouth, causes bad breath and problems with taste. People with a rare autoimmune disorder called Sjogren's syndrome also have non-functioning salivary glands.

But researchers now believe it might one day be possible to regenerate the damaged glands by stimulating the growth of nerve tissue in the organs.

The observation that nerve cells play a key role in the proper functioning of salivary glands was made about a hundred years ago in famous experiments by Russian scientist Ivan Pavlov, according to Jason Rock, a biologist at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

"He had these dogs and he would rings a bell and then feed them," he said. "And then eventually they made such a strong association there that they could salivate without having any food present just by hearing this bell. And I think that what he did is actually to cut the nerve and show that they didn't do this. So, it was a very physiological thing where they had to have neuronal input coming into the nerve to stimulate that salivation."

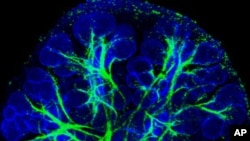

In experiments with mice, Matthew Hoffman, a biologist at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, and his colleagues found that nerve cells stimulate the growth of salivary glands early in fetal development.

"Really what we discovered was that the nerves that are present around the gland as it is developing are actually influencing the progenitor, or stem cells, as the glands develop. And we could potentially use that in a regenerative complex in the adult," he said.

Just as Pavlov's dogs stopped salivating when their nerves were cut, Hoffman says investigators found fetal salivary glands stopped growing when they removed the surrounding nerves.

Hoffman says teams of researchers from around the world have been investigating stem cell therapy as a way to regenerate salivary glands and restore function, but without much success.

"They're sort of operating a bit in the dark because they don't really know which cells it is they should be trying to maintain or purify," he said. "And so our work has really led us to identify [a] particular sub-population of cells that are in the gland that respond to the nerve and are involved in forming the tissue and likely involved in regenerating the tissue."

Hoffman envisions taking salivary tissue samples from cancer patients before they undergo radiation therapy, isolating and culturing the surrounding nerve tissue and then reintroducing the cells at a later time to begin the process of regeneration.

An article on the role of nerve cells in salivary gland development, and commentary by Duke University Jason Rock, are published in the journal Science.

Scientists Find Key to Regenerating Salivary Glands