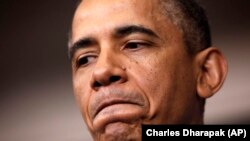

President Barack Obama is under increasing pressure to intervene in Syria’s civil war, either by ordering air strikes on government targets, arming the opposition or setting up a no-fly zone to protect the rebels trying to oust the regime of President Bashar al-Assad.

The pressure is coming from all directions – from Obama’s political rivals at home, the Syrian rebels themselves and powerful U.S. allies such as Britain, France, Israel and Turkey. All of them argue Syria has already crossed the so-called “red line” Obama himself drew nearly a year ago when he said use of chemical weapons against civilians would be a “game changer” requiring U.S. action in Syria.

The U.S. intervened in Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya, one line of reasoning goes; why does Obama seem so reluctant to take action in Syria, a country that regional analysts say could destabilize the entire Middle East and beyond?

Is it because after Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya, the American public no longer supports military intervention abroad? Is it because Syria has no big petroleum reserves to speak of? Or because the U.S. government doesn’t want to get involved in the internal disputes of yet another Muslim country?

Or maybe because – without a clear United Nations Security Council mandate -- Washington sees no diplomatic or legal basis to justify intervention in Syria.

Use of force

The 1945 U.N. charter prohibits the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, and stipulates that only the U.N. Security Council has the power to determine whether there has been an actual threat to peace and what should be done about it. In the case of Syria, permanent members China and Russia would veto any such call to action.

Cornell University Law Professor Michael C. Dorf points out another alternative: Self-defense.

“That also includes collective self-defense, and so one justification I could imagine the Obama Administration giving for sending troops to take part in hostilities in Syria would be the defense of Turkey, which is a NATO ally and which has been attacked quite recently by Syria—at least that is what appears to have happened—and that would not require any specific authorization by the U.N.”

Pragmatic approach

Robert Pape, a professor at the University of Chicago who specializes in international security affairs, has long argued the need for a new pragmatic standard for interventions. Such a standard, he says, should be based on three “pillars”—1) whether mass homicide is occurring; 2) the cost of intervention in terms of lives lost; and 3) whether intervention can bring about lasting peace.

“In the case of Syria, there is no doubt that there is mass homicide occurring in the country,” Pape said. “It’s been going on for two years and the Assad government has been a main perpetrator there and that has unleashed the Syrian civil war.”

The challenge is that any form of intervention, Pape says, would result in a tremendous loss of life.

“It would be very difficult to find ways to intervene directly in the fighting without involving tens of thousands of ground troops, if not more, in an ongoing civil war,” he said, adding that there would be no way for American troops to intervene without appearing to be fighting for one side or the other.

“And so the problem here is that this is a situation where you intervene directly in an ongoing civil war with boots on the ground in large numbers, where you are likely to have a lot of people fighting and shooting at us.”

As for the third “pillar,” Pape says the sheer size and demography of Syria undercut the contention that intervention could bring about lasting peace. Bosnia and Iraq had similar mixed demographics—that is, different ethnic and religious groups intermingled with one another. The difference, however, is that these populations were smaller and more easy to control.

In other words, given Syria’s huge size and large population -- 22 million Alawite, Sunni, Shia, Christians, Druze and Kurds living amidst one another -- there is no way a U.S. military presence could prevent a bloodbath following Assad’s fall.

Despite the practical difficulties -- whether they are legal, diplomatic or logistical -- some regional experts insist there is a moral imperative to do something when hundreds of Syrians are killed, imprisoned or displaced each day.

Pape says his approach, while practical, is also moral. “In everyday terms, helping strangers is something that you should do, as long as it doesn’t violate other moral commitments that you’ve made.”

Pape believes that in deciding on Syria, the U.S. President must consider two moral duties—first, those that our armed forces have to protect our country: If significant numbers of U.S. troops were to die, it would weaken the ability of the U.S. military to fulfill its own duty. Second, U.S. military intervention could easily end up making matters worse for the Syrians themselves. “We could end up with a situation where Syria becomes literally an ungovernable chaos,” Pape said.

Humanitarian intervention

Over time, many grew to view the U.N. Charter as too restrictive, and new norms were established. In 1948, in the wake of the Holocaust in Europe, the U.N. adopted the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, defined as any act of violence designed to destroy all or part of a specific national, ethnic, racial or religious group and obligating the international community to take whatever steps necessary to stop the killing and punish the perpetrators. The problem with the convention, however, is that it the language is vague—for example, how many members of a group would have to die before the killing could qualify as genocide?

In 2005, after the international community failed to stop the genocide in Rwanda, the U.N. General Assembly agreed on a new duty known as the “Responsibility to Protect (R2P).” This set of principles holds that states are responsible for the protection of their own citizens with the help and support of the international community. If a state fails in its obligation, the international community is obligated to intervene via sanctions and diplomacy, and, if those fail, military intervention.

These two norms form the basis of a new notion –the “humanitarian exception to the principle of nonintervention,” or, intervention without a U.N. Security Council mandate. But the notion remains problematic, according to the experts.

“It’s really not very certain in international law what the legality of humanitarian intervention is,” said Ian Hurd, associate professor of Political Science at Northwestern University “There are several bodies of international law that give you different answers. So really, you can use international law to justify a humanitarian intervention, as in Libya, but you can also use the fact of state sovereignty to argue against it.”

Instead of looking for legal justification to intervene in Syria, says Hurd, the U.S. should consider whether intervention is going to help the situation or whether it’s going to make it worse.

“In the Libya case, I think it was fairly clear that NATO hardware would help protect Libyan citizens against the government,” Hurd said. “But in the Syrian case, it’s not so clear that American or outside technology is going to help or hurt the citizens that it’s looking to protect. The Syrian government is much better armed and organized, has very good air defenses and a very well-organized and strong military compared to the Libyan government.”

According to Hurd, it was relatively easy for NATO to destroy the Libyan government’s air defenses and then go on to support the rebels from the air. “That would not be feasible in Syria without causing enormous damage,” he said. “You would probably end up killing more people by accident than you might even save.

But humanitarian intervention doesn’t have to be military, says Hurd. He points out that the U.S. is already intervening in at least two or three important ways: Putting pressure on the Russian government to reduce support for Assad and providing humanitarian relief for the people of Syria.

The pressure is coming from all directions – from Obama’s political rivals at home, the Syrian rebels themselves and powerful U.S. allies such as Britain, France, Israel and Turkey. All of them argue Syria has already crossed the so-called “red line” Obama himself drew nearly a year ago when he said use of chemical weapons against civilians would be a “game changer” requiring U.S. action in Syria.

The U.S. intervened in Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya, one line of reasoning goes; why does Obama seem so reluctant to take action in Syria, a country that regional analysts say could destabilize the entire Middle East and beyond?

Is it because after Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya, the American public no longer supports military intervention abroad? Is it because Syria has no big petroleum reserves to speak of? Or because the U.S. government doesn’t want to get involved in the internal disputes of yet another Muslim country?

Or maybe because – without a clear United Nations Security Council mandate -- Washington sees no diplomatic or legal basis to justify intervention in Syria.

Use of force

The 1945 U.N. charter prohibits the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, and stipulates that only the U.N. Security Council has the power to determine whether there has been an actual threat to peace and what should be done about it. In the case of Syria, permanent members China and Russia would veto any such call to action.

Cornell University Law Professor Michael C. Dorf points out another alternative: Self-defense.

“That also includes collective self-defense, and so one justification I could imagine the Obama Administration giving for sending troops to take part in hostilities in Syria would be the defense of Turkey, which is a NATO ally and which has been attacked quite recently by Syria—at least that is what appears to have happened—and that would not require any specific authorization by the U.N.”

Pragmatic approach

Robert Pape, a professor at the University of Chicago who specializes in international security affairs, has long argued the need for a new pragmatic standard for interventions. Such a standard, he says, should be based on three “pillars”—1) whether mass homicide is occurring; 2) the cost of intervention in terms of lives lost; and 3) whether intervention can bring about lasting peace.

“In the case of Syria, there is no doubt that there is mass homicide occurring in the country,” Pape said. “It’s been going on for two years and the Assad government has been a main perpetrator there and that has unleashed the Syrian civil war.”

The challenge is that any form of intervention, Pape says, would result in a tremendous loss of life.

“It would be very difficult to find ways to intervene directly in the fighting without involving tens of thousands of ground troops, if not more, in an ongoing civil war,” he said, adding that there would be no way for American troops to intervene without appearing to be fighting for one side or the other.

“And so the problem here is that this is a situation where you intervene directly in an ongoing civil war with boots on the ground in large numbers, where you are likely to have a lot of people fighting and shooting at us.”

As for the third “pillar,” Pape says the sheer size and demography of Syria undercut the contention that intervention could bring about lasting peace. Bosnia and Iraq had similar mixed demographics—that is, different ethnic and religious groups intermingled with one another. The difference, however, is that these populations were smaller and more easy to control.

In other words, given Syria’s huge size and large population -- 22 million Alawite, Sunni, Shia, Christians, Druze and Kurds living amidst one another -- there is no way a U.S. military presence could prevent a bloodbath following Assad’s fall.

Despite the practical difficulties -- whether they are legal, diplomatic or logistical -- some regional experts insist there is a moral imperative to do something when hundreds of Syrians are killed, imprisoned or displaced each day.

Pape says his approach, while practical, is also moral. “In everyday terms, helping strangers is something that you should do, as long as it doesn’t violate other moral commitments that you’ve made.”

Pape believes that in deciding on Syria, the U.S. President must consider two moral duties—first, those that our armed forces have to protect our country: If significant numbers of U.S. troops were to die, it would weaken the ability of the U.S. military to fulfill its own duty. Second, U.S. military intervention could easily end up making matters worse for the Syrians themselves. “We could end up with a situation where Syria becomes literally an ungovernable chaos,” Pape said.

Humanitarian intervention

Over time, many grew to view the U.N. Charter as too restrictive, and new norms were established. In 1948, in the wake of the Holocaust in Europe, the U.N. adopted the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, defined as any act of violence designed to destroy all or part of a specific national, ethnic, racial or religious group and obligating the international community to take whatever steps necessary to stop the killing and punish the perpetrators. The problem with the convention, however, is that it the language is vague—for example, how many members of a group would have to die before the killing could qualify as genocide?

In 2005, after the international community failed to stop the genocide in Rwanda, the U.N. General Assembly agreed on a new duty known as the “Responsibility to Protect (R2P).” This set of principles holds that states are responsible for the protection of their own citizens with the help and support of the international community. If a state fails in its obligation, the international community is obligated to intervene via sanctions and diplomacy, and, if those fail, military intervention.

These two norms form the basis of a new notion –the “humanitarian exception to the principle of nonintervention,” or, intervention without a U.N. Security Council mandate. But the notion remains problematic, according to the experts.

“It’s really not very certain in international law what the legality of humanitarian intervention is,” said Ian Hurd, associate professor of Political Science at Northwestern University “There are several bodies of international law that give you different answers. So really, you can use international law to justify a humanitarian intervention, as in Libya, but you can also use the fact of state sovereignty to argue against it.”

Instead of looking for legal justification to intervene in Syria, says Hurd, the U.S. should consider whether intervention is going to help the situation or whether it’s going to make it worse.

“In the Libya case, I think it was fairly clear that NATO hardware would help protect Libyan citizens against the government,” Hurd said. “But in the Syrian case, it’s not so clear that American or outside technology is going to help or hurt the citizens that it’s looking to protect. The Syrian government is much better armed and organized, has very good air defenses and a very well-organized and strong military compared to the Libyan government.”

According to Hurd, it was relatively easy for NATO to destroy the Libyan government’s air defenses and then go on to support the rebels from the air. “That would not be feasible in Syria without causing enormous damage,” he said. “You would probably end up killing more people by accident than you might even save.

But humanitarian intervention doesn’t have to be military, says Hurd. He points out that the U.S. is already intervening in at least two or three important ways: Putting pressure on the Russian government to reduce support for Assad and providing humanitarian relief for the people of Syria.