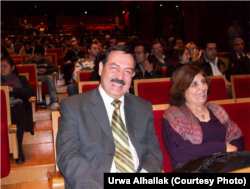

Once, Taofik Alhallak made his living interviewing Syrian artists, thinkers and doers, and scripting children’s shows for his television production company. Now, the 65-year-old huddles at his laptop in northern Virginia, an asylum-seeker chronicling the devastation of his homeland while trying to help save it.

"Hundreds of thousands of Syrian children [are] out of school today," with civil war disrupting classes and leaving youngsters poorly educated and vulnerable, he blogged a few days ago for his website. He urged parents there to guard against overtures from the Islamic State group, saying, "Daesh … turns them [youths] into thugs."

The website – SalebMujeb.com, Arabic for "Positive Negative" – gives Alhallak a voice in Syria, one that he says the Assad government has repeatedly tried to silence.

"Every article is about the revolution," explains his son, Urwa Alhallak. Most of the posts "are spreading awareness of how society could move into democracy."

Shortly after Syria’s pro-democracy protests began in March 2011, the elder Alhallak began writing supportive Facebook posts. He criticized the government’s hard-line responses, which began with security forces killing several demonstrators and escalated to the barrel-bombing of countless civilians. And he blamed Syria’s government for sending a man to his home in a Damascus suburb with a warning.

"He said: 'Either you stop writing or I will kill you, burn down your house and kill your family,'" Taofik Alhallak recalls, with his son translating.

That knock on the door, in mid-2011, propelled Alhallak and his wife on a four-year, angst-ridden odyssey through several countries, finally leading in October to this modest townhouse in a Virginia suburb of Washington, D.C.

Increase in asylum-seekers

Now Alhallak and Zahrieh Alsouso are among a growing number of Syrians seeking political asylum in the United States. Some 1,582 filed new cases in fiscal 2014 and another 633 did so in the first half of fiscal 2015, The Washington Post reported, citing U.S. Department of Homeland Security data.

Asylum-seekers, like refugees, must have faced or fear persecution because of race, religion, nationality, political views or social-group affiliation. The difference, at least in the United States, is that they’re already in the country in which they're seeking refuge.The United Nations refugee agency, UNHCR, says an asylum-seeker is a self-described refugee "whose claim has not yet been definitely evaluated."

Refugees are caught up in the debate over how welcoming the West should be – especially to Muslim Syrians – in the wake of the November 13 terrorist siege in Paris for which the Islamic State group claimed responsibility. A purportedly fake Syrian ID was found near the body of a slain attacker, fomenting concerns that violent extremists were sneaking in with the migrants streaming into Europe from Syria and other countries ravaged by war and poverty.

The United States has resettled at least 2,261 Syrian refugees since October 1, 2011, the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute reports, and U.S. President Barack Obama has pledged to bring in at least another 10,000 over the next year. The Republican-led House of Representatives recently voted to suspend resettling Syrian refugees pending more study of national security measures. Obama has vowed to veto the measure if it makes it to his desk.

See related video: 'Admitting Syrian Refugees Fiercely Debated in US'

Blurred lines

Suspicions have spilled over, blurring the lines between newcomers and those with deep roots in the United States, between peoples of Middle Eastern descent, between those who are Muslim and those who practice other faiths or none at all.

"I feel this little wall every time I meet with friends," says Urwa Alhallak, 35, who arrived in the United States in 2007 to study filmmaking. "I say I’m from Syria, there’s this silence.... I feel like inside they will think: 'Syrian? Maybe terrorist?' It’s not going to change easily."

He and his parents describe themselves as secular Syrians. They remember Damascus as a diverse and tolerant capital city. "We have Muslims, Christians Jews, we always lived together. It’s a mix,” says the younger Alhallak, who goes by the nickname Al.

In Syria, Taofik Alhallak was well known for his television work – as host of the 1976-’86 cultural affairs show "Positive and Negative" and for the children’s show. He and his wife, a cognitive psychologist, raised two daughters and their son, the youngest, in a Damascus suburb.

The government made a point of keeping prominent people like Alhallak in check, the family says.

In 1989, government representatives took the "Positive and Negative" master tapes and recorded over them with speeches by then-President Hafez al-Assad. "They selected this show that everyone loved. From the 11 years, he has just 15 minutes," Alsouso laments about her husband's work.

Alhallak later developed another program, "The Country Son," celebrating Syrian scientists, artists and intellectuals. "The regime stopped his show around two years before the revolution, for no reason," his son says. "… Those people were not recognized by the government for their achievements. His show recognized their work…. We believe that the regime wasn’t so happy about that."

Homeless and harried

The pressure grew after the 2011 uprising, and the elder Alhallaks fled their home in the Damascus suburbs. "When they left, the government came and took it over," says Al, adding that the house remains occupied by backers of Bashar al-Assad’s government.

The elder Alharrak and Alsousa left with little cash and became itinerants, staying for a few months each in several locations. First it was in London with one daughter's family, then in Tunisia with the other's. They moved on to Egypt when Alharrak was offered a job with a Cairo-based TV station that supported a peaceful Syrian revolution. But a friend working at the Syrian embassy there heard Assad loyalists "might need to eliminate him," says the son.

The parents joined him in California in July 2012 – both held tourist visas – and applied for political asylum a few months later. They’re still waiting for a decision; the busy Los Angeles division of the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services has the longest lag even for interviews, according to a scheduling bulletin.

Role reversals

Now a freelance film editor and visual effects specialist, Al – a permanent U.S. resident – has been his parents’ primary source of support since they landed in California.

"I have been able to pay the rent and do all other things like paperwork, translation, transportation," he says, noting his parents "didn’t bring any money." But, he adds, we "were lucky to have [a] few friends who helped us," a debt he intends to repay when "they get asylum or we are able to get our house back to sell it."

The family relocated in October to northern Virginia to be closer to friends.

A longtime family friend – a Syrian-American real estate agent – found them the townhouse to rent. Another friend’s mom enlisted her neighbors to furnish it.

"One of them delivered the donations here, like the dining table upstairs," and even stayed to set it up, Al marvels. The townhouse already had a spinet piano, where his mom picks out music by Franz Liszt and other Western composers.

Work continues

His parents fit the general profile of most U.S. arrivals from Syria since 2011: They came to join family, they’re older, highly educated and not employed.

But both continue to work, unpaid.

Taofik Alhallak maintains his Facebook page and a YouTube channel "to document the peaceful protests in Syria that asked for freedom and democracy," he says through his son. (Both parents have a shaky but growing command of English.)

He has produced roughly 60 segments, each running several minutes. "It’s for the Syrian people in general, but I try to translate for French and English," he adds.

Alsouso, the psychologist, counsels former patients who were able to flee – mostly to countries in the Middle East or Europe. She speaks with them by Skype. Those who remain in Syria tend to be out of touch, given sporadic electricity, much less Internet service.

"I become strong when I talk to them to give them hope and strength, but I myself am not very settled," Alsouso admits. She encourages them, and reminds herself, to "get involved with the societies they live with, not dwell in the past."

Relocation difficulties

The family hasn’t had to endure all the challenges facing refugees, including crowded, uncomfortable camps and treacherous land and sea crossings.

But they, too, have encountered hardships.

They left behind identities – "my dad’s position as a famous Syrian personality, our house that we grew up in, memories, relatives," says the son. The elder Alhallak’s sister’s son, a dentist, "was detained by the regime and killed under torture. That was in 2013."

While the family feels safe in the United States, Al says, he worries about his parents' health. They had qualified for Medi-Cal – California’s version of the federal Medicaid program for low-income adults – but haven't, as yet, for its Virginia equivalent. "What if they get sick?" he wonders.

(The Center for Immigration Studies, a Washington-based organization pushing to curb U.S. immigration, last month released a report suggesting it would be more cost-efficient to subsidize Middle Eastern refugees in their region rather than resettling them in the United States. Asylum-seekers may qualify for medical assistance and other aid through the federal Office of Refugee Resettlement, the government says.)

Alsouso also frets that she and her husband can't visit their daughters and three young grandchildren. Not only is their immigration status unresolved, but they lack the money to travel overseas.

"I just want to get medical benefits and papers to travel," she says.

But she’s grateful for "very kind people" she has met in the United States, including new neighbors in Virginia, Alsouso says. "I like to be open to [all] the American societies, not just the Syrians."

Her husband says if he got asylum, he’d "become American and be a good person. We believe in the same things: freedom, dignity."

Taofik Alhallak wants the same for people in Syria and is trying to help them through journalism, his son says. "My parents didn’t really care about money or the house. They want a free, strong Syria, and they didn't care if they lose everything for this cause."

VOA’s Jeff Swicord and Elizabeth Cherneff contributed to this report.

See related video: 'Syrian Blogger Seeking US Asylum'