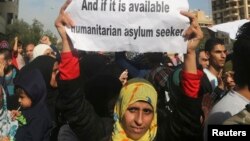

More than three million people have fled the Syrian war to other countries in recent years and one of the most vulnerable groups among them are Palestinians, displaced already for generations by the Arab-Israeli conflict. Palestinians from Syria say, between legal restrictions and soaring rents, life is hard in Lebanon. But families say life is much harder for the neighbors they left behind.

At the heart of the Arab-Israeli conflict is the ‘right of return,’ a principle drawn from international human rights law that says every person has the right to go home to their original country.

For many Palestinians that means returning to Israel, even if it was their great-grandparents who originally fled the country.

But at this Palestinian home in Lebanon, family members say the war in Syria has redefined their right of return. They want to go home - to a peaceful Syria.

Wedad Subhie says she, her husband and children fled Syria without identification a year ago, paying $4,000 for a taxi for the roughly 100-kilometer trip to this Beirut suburb.

Since her family came to Lebanon, they have been desperately poor and isolated. They can travel within their neighborhood, she says, but don’t seek help from the United Nations because they don’t have IDs, and, like many refugees, are not in Lebanon legally.

Lebanese American University Political Science Professor Sami Baroudi says the refugee crisis in Lebanon is defined by legal chaos.

“It’s very arbitrary. Someone may stop you and someone may not stop you. You don’t even know as a Syrian displaced what are your rights and what are not your rights,” says Baroudi.

Discrimination against refugees from Syria is also increasing, he says, as Lebanon feels the strain of hosting more than a million impoverished people in a country of only four million.

No clear policy

And without a clear national policy on how to deal with the refugee influx and continued violence spilling across the border, local governments have taken matters into their own hands, often with public support.

“So many municipalities have taken the law into their hands. I’m sure you’ve seen the signs, trying to be polite, saying ‘We request our Syrian brethren not to be on their motorcycles after 6 p.m.’ So in so many places they are under curfew which is the epitome of racism. But there is no legal body to regulate anything,” says Baroudi.

At Subhie’s home, her 24-year-old son, Abd el-Kader says the family’s lack of legal status makes it nearly impossible to find work, so he alone supports the family of eight on $500 a month.

But he says life is much more difficult for the people still stuck in Yarmouk, a Palestinian refugee camp in Damascus that continues to see fierce fighting. UNRWA, the U.N.’s Palestinian refugee agency, says in recent days they have been completely barred from distributing food aid in Yarmouk.

UNRWA also says that of the more than quarter million Palestinian refugees displaced by the Syrian war, about 44,000 have been counted in Lebanon.

But at this home, Mustapha Ali says no one from the U.N. has ever counted him or his seven children.

Ali says he ran away from Syria during heavy fighting and couldn't take his papers.

Ali says he also doesn’t even try to access the U.N. assistance that could be available to him as a Palestinian or a Syrian, because he is afraid of being stopped at military checkpoints.

When he is stopped, he says, pointing to his bushy Saddam Hussein-style mustache, he tells officials he’s actually an Iraqi to avoid suspicion.