North Korea’s sudden nuclear test is prompting analysts in Seoul and Washington to wonder what might have motivated Pyongyang to make the move.

Pyongyang announced Wednesday that it had successfully tested a miniaturized hydrogen bomb, also known as a thermonuclear bomb, which is more powerful than a conventional atomic bomb.

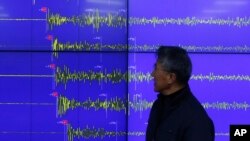

A few hours before the announcement by North Korea’s state-run Korean Central News Agency, earthquake agencies in the United States, Japan, China and South Korea detected unusual seismic activity near the Punggye-ri nuclear test site, where three previous tests have been conducted.

Claim questioned

However, the nature of the test remains unclear. The United States expressed skepticism about the North Korean claim. White House press secretary Josh Earnest said the initial analysis by U.S. intelligence agencies was “not consistent with North Korean claims of a successful hydrogen bomb test.”

A South Korean lawmaker said his country’s intelligence agency estimated the test involved an explosive yield smaller than that produced in the last atomic weapon test, in 2013.

Olli Heinonen, a former deputy director general at the U.N.’s International Atomic Energy Agency, warned against rushing to a conclusion, saying the analysis could take weeks.

What Pyongyang might be trying to accomplish with the test is another puzzle. Analysts say there are some key differences between Wednesday’s test and previous tests. This time, Pyongyang failed to provide any public warning of an imminent test. It also broke with the previous pattern of conducting a long-range missile test prior to a nuclear test.

Leader's intentions unclear

It is also unclear what Kim Jong Un is really intending to do. In his New Year’s speech, Kim appeared to stress the economy over military power, avoiding direct references to usual nuclear threats or the country’s policy of pursuing economic and nuclear development simultaneously.

Instead, the young leader called for improved ties with Seoul, sparking widespread speculation that he might pursue a conciliatory course as part of preparations for a major party convention in May. Kim is expected to announce key state policies and a reshuffling of party officials and governing organizations during the rare gathering.

Gary Samore, who served as White House coordinator for arms control and weapons of mass destruction from 2009 to 2013, questioned whether the provocative move served Pyongyang’s interest.

“I think it’s very difficult to understand what national interest was served by testing right now. It may be another indication of Kim Jong Un’s very poor judgment,” the former official said.

Political ties?

Stephen Noerper, senior vice president at the New York-based Korea Society, said Pyongyang’s action might be tied to domestic politics. The North Korean regime appears to be trying to demonstrate its nuclear capability to its citizens in anticipation of important political events such as Kim’s birthday, which is Friday.

“I think that North Korea was testing from a domestic perspective in advance of Kim Jong Un’s birthday, and maybe more critically ahead of the May party congress, which will be the first to be held since 1980,” Noerper said.

Nam Kwang-kyu, a professor at Korea University in Seoul, said the test might be aimed at “boosting Kim’s image as a leader and promoting his achievements.”

Some say the way North Korea’s state media made the announcement showed the media’s deliberate attempt to link the test to Kim. In a rare move, North Korea’s state television carried images of a “written order” by Kim.

In a report this week, Cheong Seong-chang, director of unification strategy at the Sejong Institute in Seoul, said Kim has been showing his own governing style in major addresses since he took power in late 2011 in an apparent attempt to elevate his status. Between 2012 and 2016, the number of Kim’s references to his predecessors in his New Year’s speech and joint editorial that outlines the county’s policies for the coming year dropped from 76 to 11, according to Cheong.

Strong condemnations

The latest test drew widespread condemnation from the international community. Existing U.N. sanctions prohibit North Korea from conducting nuclear tests. The U.N. Security Council vowed Wednesday to pursue new sanctions against the communist country, calling the test a “clear violation” of previous U.N. resolutions.

Kim Hwan Yong and Jee Abbey Lee contributed to this report.