During the few daily hours of electricity in Yemen’s capital, Sana'a, there are two options for watching state-run Yemen TV.

One is the channel run out of Sana'a by the Houthis, a group that currently controls much of Yemen. The other is broadcast out of the Saudi capital, Riyadh, and run by the former government, now in exile. Both are called al-Yemen.

Many people watch both but trust neither.

"There are no facts in the two channels," said Leila Moukbil, a security contract supervisor in Sana'a. "So I need to watch the two to see what’s the crimes that Saudi Arabia [commits], and what’s the crimes that al-Houthi [does]."

Modern warfare is increasingly as much about information manipulation as it is about fighting forces. In Yemen, the government-in-exile is creating reports that look like the state media now controlled by Houthis, but it spins the story the other way.

Not fooled?

Yemenis say the tactics won’t work, for two reasons: First, there’s barely enough electricity for television. Second, they know propaganda when they see it.

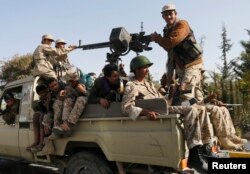

Yemenis have suffered more than two months of airstrikes in a war many see as entirely between foreign powers. On paper, one side features the Yemeni government-in-exile led by President Abd-Rabbu Mansour Hadi, plus allies including Saudi Arabia. The other combines the Houthi militants and their supporters. On the ground, combatants are referred to simply Saudi Arabia and the Houthis, longtime enemies.

Misinformation on the dueling Yemen TV channels hurts both sides’ credibility, Moukbil said.

"For example, al-Yemen in Riyadh: It makes Saudi Arabia as the hero and al-Houthi [look] bad," she added. "And the same in al-Yemen in Sana'a: It makes Saudi Arabia the criminal and al-Houthi the hero."

Little appetite for news

Other Yemenis say that, as the war drags on, the humanitarian crisis has overwhelmed all aspects of life, leaving politics of little interest. The World Health Organization said nearly 2,000 people were killed between March 19 and May 22. The United Nations said 20 million people – 80 percent of the country – needs emergency food, water and medical supplies.

Continuous bombings, along with closed land, sea and air borders, are driving up support for the Houthis, according to Nasser Arrabyee, a prominent Yemeni journalist and director of the media company Yemen Alaan.

He described himself as "secular. I am not Shia, I am not Sunni. After the Saudi aggression, everything changed" – for him and many others, he said.

The fact that Hadi left Yemen months ago, yet claims to be the legitimate leader, ignores the reality of who is in charge.

"Hadi is legitimate, he was legitimate," Arrabyee said, changing tenses. "He was the president, but he failed. He failed, and his legitimacy expired."

Growing hope for pact

There is, however, increasing hope that the combatants can come to an agreement and finally halt the bombing, Arrabyee said.

On Friday, the Houthis announced they will participate in talks in Geneva expected later this month. Previous talks have included Houthi allies, but it was never clear if the group itself would adhere to any deal they struck.

The ongoing conflict has forced changes in Yemen’s newsrooms, said former TV announcer Khalil al-Qahiri, who has left journalism.

"There are those who will work in television under any existing regime," he said. "Others have totally refused to deal with the new situation and they either now stay at home or have found a new opportunity."

Another broadcaster, Mohamed al-Samawi, said TV news in Yemen is part of a bigger problem in the Arab world, with more and more channels operating as polarizing political forces.

The shortage of neutral news aggravates the conflict by increasing tensions between groups that previously lived in peace, said al-Samawi, speaking at a Sana’a restaurant.

"Frankly," al-Samawi said, "we need in Yemen and in the Arab world neutral and professional TV channels that report the reality and do not put poison in the honey."

Fras Shamsan contributed to this report from Sana’a.