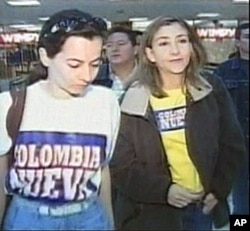

In 2002, Íngrid Betancourt was a Colombian senator, campaigning for president as the candidate of the Green Oxygen party, when she and her campaign manager, Clara Rojas, were kidnapped by guerillas from the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or FARC. In a second, as she writes in a new memoir, Even Silence Has an End, she had become a captive - her prison, the Amazon jungle.

Until her rescue in 2008, Betancourt spent her days at the end of a chain, eating mostly rice and beans, and subject to the cruelty and whims of her guards. At night it was so dark she could not see her own hands in front of her, much less the dangers all around.

"There are all kinds of snakes, bugs, tarantulas," she said in an interview recently. "That's at night. And during the day we were chained to a tree by the neck, so we couldn't move anywhere. If we were lucky, we would be able to hang a hammock and stay in the hammock for the day under a mosquito net, but we could also be forced to just sleep on the floor on a plastic sheet."

As a member of Colombia's elite, with dual French citizenship, Betancourt says, she was often treated with special harshness.

"First, because I was a politician and no one likes politicians, especially the guerillas," she said. "And whenever I tried to explain to them that I was fighting to change the system, they would turn and say, 'Politicians always say the same.' And they were right. And they hated me because I was a cultivated person and they had no education. They thought I could manipulate them, that I could trick them. And I was a woman, and this is a very macho society, where they are very suspicious of women."

Betancourt and Rojas were not the only hostages. The FARC constantly abducted new captives, including three American military contractors taken after their plane crashed. The guerillas regularly filmed them all, to prove to the outside world that they were alive and thus still useful for ransom or as bargaining chips. Betancourt tried to escape five times, but each time was recaptured - and subjected to new punishment.

"You know you are in extreme situations, you cope with it as much as you can," she said. "For me, the only thing that was important in those humiliating times, very hard, and some sadistic situations where we had the guards being violent and cruel, what I thought was always keeping my dignity, as much as I could preserving the respect I had for myself," she said.

At times hostages were released in prisoner exchanges or for humanitarian reasons. Clara Rojas, who became pregnant by a rebel and gave birth to a baby boy, was released in January 2008. Her son, who had been taken from her by the FARC, was found in the care of a peasant family, and returned to her. But Betancourt was never among the few released. She was too valuable as a bargaining chip. "The commander once told me, 'You're going to be out here when you're a grandmother," she recalled. "He said, 'You will be out when your hair will be on your heels.'"

In July of that year - when Betancourt's hair had grown waist-length - a helicopter team landed at the camp to transfer 14 of the hostages. The team seemed to be rebels allied with the FARC. Betancourt despaired that they would be moved even deeper into the Amazon.

"I thought, deeper? We will never, never come out of this again. I thought it's going be 10 or 20 more years of abduction. So, we didn't want to get into that helicopter. We went forth because we had the rifles in our backs."

But once the helicopter lifted off, it turned out the "rebels" were not what they seemed. They quickly subdued several FARC guerillas who had accompanied the hostages aboard. "And then one of them shouted, 'We're the Colombian army and you're free!'" Betancourt recalled. In an elaborate operation, the Colombian army had tricked FARC commanders into unwittingly giving up their prisoners.

Betancourt was reunited with her family, including her two children, who had been 13 and 16 when she was captured. She says the "life of love" she had known before the abduction helped her to survive. "Feeling loved by my children, by my mother, by my father, gave me the strength to want to escape all the time. It was really my obsession," she said. "But I think for me there were also other kinds of love, the love of God, which for me was very important."

She said the love of her fellow hostages also kept her alive, even though several of them, including Clara Rojas and two of the three American hostages, have since criticized her. In their chapters of a jointly written memoir, former hostages Keith Stansell and Tom Howes, said that Betancourt was selfish and once supervised FARC guards in a search to retrieve embarrassing letters she had written to the third American hostage, Marc Gonsalves. Betancourt strongly denies those accusations, and says she had no influence among the FARC guards.

She was also widely denounced in Colombia when she announced plans to sue the government for compensation. She later dropped the lawsuit.

Now living in France and the United States, Betancourt says she will continue lobbying on behalf of kidnapping victims in Colombia, where some human rights groups estimate guerrillas still hold 600 to several thousand hostages. "They are targeting the peasants to take their lands and to get rich just expropriating illegally the work of those peasants," she said, adding that the Colombian army has succeeded in isolating FARC and may well defeat it.

But ridding Colombia of FARC is only the beginning, Betancourt said. "The first thing we have to fight in Colombia is corruption. We need a strong judicial system, and we need a strong government that can afford to address the issues that half of the population is having right now, which is security, the possibility to be protected by the law and the justice, and the access to jobs."

Those were the issues that had led her to run for president of Colombia, she said. In video from her 2002 campaign, she appears confident and optimistic, unafraid. Eight years later, she is a different woman, more tentative. She said she is still recovering from her years as a captive, and has no desire to return to politics, at least for now.