State-of-the-art electronics, from cell phones to laptops, seem to be everywhere these days. But most of us don’t know how they work or that they hide a dirty little secret inside: Many are made with minerals that originate in conflict zones like the Democratic Republic of Congo and neighboring countries.

Eastern Congo’s mines are controlled by militias and rebel groups that use profits from minerals like gold, tungsten, tantalum and tin to perpetuate the DRC conflict, which has claimed more than five million lives since 1998.

“These militias make millions and millions of dollars,” said Sasha Lezhnev, a consultant with Enough, a project of the Center for American Progress to end genocide and crimes against humanity. “We estimated that they made about $180 million from trading in these minerals last year and they’re able to continue their existence and their armed struggle on the basis of this trade.”

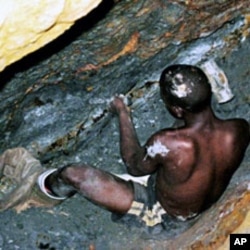

By comparison, Lezhnev says the miners only earn between $1-5 a day working either for an armed group or for someone who pays off an armed group. The prices of the minerals vary, but in the case of tantalum, for example, the ore can fetch up to 50 times what miners earn.

From mine to smelter

Many of the minerals are mined by hand in small-scale artisanal mines, where they are close to the surface.

Ores are typically processed and concentrated on-site. After that, the processed minerals are shipped to a regional center for further concentration, explains David Menzie, Chief of the International Minerals Section at the United States Geological Survey.

|

What Are Conflict Minerals? |

|

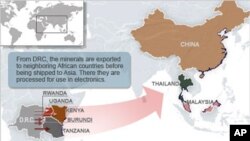

The minerals pass through a number of hands, from miners to smugglers to traders to wholesalers, before being shipped out of DRC to neighboring countries.

“Many of the minerals actually get smuggled out to Rwanda, to Uganda and to Burundi,” said GRG’s Lezhnev. “And from there, they get flown out or taken by road to Kenya and Tanzania. And then they get flown out mostly to East Asia for smelting.”

Smelters in Malaysia, China and Thailand turn the rock ores into metals and sell them to components companies, which, in turn, shape them into various parts for consumer products, depending on the metal.

Regulating trade

Not all electronics products use conflict minerals. But those that do have been the target of advocacy groups seeking to end their trade. Their efforts recently yielded congressional legislation, which was signed into law by President Obama in July.

The new U.S. law requires electronics companies and manufacturers to ensure that their supply chains are free of conflict minerals. That means companies will be required to provide increased transparency and disclosure throughout the supply chain, says Stephen D’Esposito, President of RESOLVE, a non-profit organization that mediates conflicts.

“The burden falls on manufacturers to be able to look into their supply chain and show evidence that where they’re getting their supply from and that the people who they’re getting it from and that the people who they’re getting it from know where they’re getting it from and so on down the line.” said D’Esposito. “It takes what the electronics companies were starting to do on a voluntary basis on their own and makes it a legal requirement.”

Some companies are protesting the complexity of requirements in the new law. Others have put their Congo supply chains on hold, pending a review of their sources. And some, like Intel, Motorola and HP, have taken stronger action, with Intel beginning a process to audit its tantalum supplies.

The question D’Esposito asks is whether conflict minerals can be traced to their source, given the many stages they go through before being sold to electronics companies. “Is it possible to create a supply chain where you know your source,” he asked.

One of the challenges, says D’Esposito, is that supply chains are typically very hard to trace in an informal mining sector.

“If you’ve got small-scale mining where there is not good record keeping … where the government doesn’t necessarily support the mining or validate it, then the record-keeping tends to be difficult or non-existent,” noted D’Esposito. “What has to happen is changes have to occur in the supply chain so that there’s actual paperwork that’s credible that shows you where things came from.”

The tracking task becomes even more difficult if the minerals are mined in regions engaged in armed conflict. By the time the minerals reach the smelter, it is all but impossible.

Both D’Esposito and USGS’s David Menzie say the easiest way to trace conflict minerals is to set up a certification system at the smelter. But that means the smelter will have to ensure that all the minerals are coming from legitimate sources.

GRG’s Sasha Lezhnev takes the approach a bit further, saying the best way is to ensure that no conflict minerals are used is to trace, audit and certify.

“So companies should trace their minerals back to their smelters and back to the mines,” said Lezhnev. “Number two: they should have audits and monitoring conducted of that process independently. And then thirdly, they should contribute to concrete certification efforts on the ground out in Central Africa, which is really going to make this happen.”

Who pays?

Lezhnev maintains that the costs of reforming the supply chain are minimal. But RESOLVE’s D’Esposito argues that it is still unclear what the process will cost, since it depends on the supply, the market price of the minerals, and interest on the part of electronics companies in supporting the development of valid and conflict-free supply chains.

“This complementary strategy will cost money. The question is who will bear the burden of those costs if these systems work? Right now, systems development is being funded by government aid agencies and voluntary donations from some electronics companies. If these systems take hold they will have to be financially self-sustaining and this could increase costs.”

Even if the tracking system works, Herbert Weiss of the Woodrow Wilson Center says Congo miners not only risk losing their jobs but could face increased raids from militias if their mining profits drop.

“One of the dangers in all of this is that if [conflict minerals] are traced to the Congo, if that is successful, you’re talking about thousands of small artisanal miners losing their wherewithal, losing their bread and butter every day,” said Weiss. “What is going to happen to all of these artisanal miners who are making a living, even though a very, very small percentage of the value of what they are mining goes to them because the intermediaries are the ones that gain the main profit?”

Weiss suggests establishing a fund to support miners who lose their livelihoods as a result of the tracing efforts and help them find work in other industries.

There is no perfect answer to the problem of DRC’s conflict minerals. But RESOLVE’s D’Esposito says U.S. law now helps put the debate on the right track.

“The legislation takes you to a place where consumers can start to know in some jurisdictions that their products are conflict-free. And companies who are part of that scheme … may be doing it worldwide,” said D’Esposito.

Even with the legislation in place, there is no guarantee that these minerals won’t come from conflict zones. Militias controlling eastern Congo’s mines can easily sell their products to companies not subject to U.S. laws. But experts hope that the legislation will set an example for companies in other countries to curtail, if not eliminate, conflict minerals from their supply chains.