Russian Central Bank chief Elvira Nabiullina was probably referring to her own bank’s forecast, released a few days before she spoke. In that report, the Bank of Russia predicts growth of between 1-1.5 percent in 2017 and 2018. By comparison, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is more cautious, forecasting 1.1 percent growth in Russia in 2017; the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) is even less optimistic, foreseeing growth of 0.75 percent. In the summer of 2016, the Bank of Russia noted that, according to its data, the recession in Russia had ended in the second quarter of that year with slow growth predicted going forward. However, the bank’s assessment ran counter to official data at the time.

At the start of 2017, the Russian state statistics service Rosstat changed the way it assesses economic activity and production in the country, using metrics in line with those in the European Union.

As a result, in February Rosstat released rejiggered data, according to which, the recession in Russia had not been so bad. The new estimates surprised not only economic experts but apparently the government as well. So, instead of falling 3.7 percent as the old data showed, the Russian economy only sank 2.8 percent in 2015 according to the numbers crunched under the new methodology. Moreover, Rosstat on March 31 released recalculated data for 2016, which also were rosier than the original figures. The recalculated data showed the recession had in fact ended by the fourth quarter of 2016, with 0.3 growth now registered.

Interestingly, the key factor in this reappraisal, as noted by Rosstat chief Aleksandr Surinov, was recalculating the input of medium and small business, even though Rosstat itself acknowledged this sector comprised only 19.9 percent of the economy in 2015. That is three to four times lower than in European countries.

The Bank of Russia is now forecasting annual growth in the first quarter of 2017 of between 0.4 -0.7 percent. If that prediction turns out to be true, Russia’s recession then will be “formally” over since there would have been two straight quarters of growth. But it may still be too early to cheer since other agencies were issuing less rosy forecasts not too long ago.

In mid-October 2016, the Ministry for Economic Development unveiled its long-term economic outlook for Russia to 2035. Its “base” scenario assumes slow economic growth in Russia over the next 20 years – on average 2 percent per annum (1.7 – 2.6 percent), about 1.5 times lower than global predicted growth for the same period. And the ministry has forecast only 0.6 percent GDP growth in Russia for 2017.

However, a month after releasing these relatively gloomy numbers, the head of the Ministry for Economic Development, 60-year-old Aleksei Ulyukaev, was arrested on charges of extorting $2 million from Rosneft, the state-controlled Russian energy giant whose head, Igor Sechin, is a close ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

It didn’t take long for the ministry to find a replacement. Two weeks after Ulyukaev was ousted, 34-year-old Maxim Oreshkin, who had been a deputy at the Finance Ministry, was picked to head the Ministry for Economic Development on November 30, 2016. In February, Oreshkin told Putin that economic growth of some 2 percent in 2017 was now expected, three times higher than what the ministry had predicted under his predecessor. This just a year ahead of scheduled presidential elections in Russia.

But in mid-March Rosstat released data for January and February showing a significant slowdown in the economy. Instead of absorbing the new data, Oreshkin rejected the numbers, criticizing the methodology used by Rosstat. Quickly it was proposed that Rosstat be again subordinate to the Ministry of Economic Development. That had happened twice over the past 15 years, but every time Rosstat ultimately returned to answering only to the federal government. German Gref, current head of Russia’s Sberbank and a former Minister for Economic Development, said in 2009: “Data should be completely independent. I consider it a mistake of the government that Rosstat is now subordinate to the Ministry of Economy. It’s the worst possible thing – playing with statistics.” Nevertheless, Putin on April 3 signed a decree placing Rosstat under the direction of the Ministry for Economic Development.

Barring any unforeseen shocks, the Russian economy should experience some growth in 2017 most experts acknowledge. The question is how sustainable will it be? For example, third quarter GDP growth in 2016 of 0.1 percent was due to two factors – an especially robust harvest in Russia that year, and the unseasonably cold autumn that year in most of Western Europe which forced many countries there to make record purchases of Russian gas, explained former Deputy Finance Minister and former Deputy Chairman of the Russian Central Bank, Sergei Aleksashenko, currently a nonresident senior fellow at the Washington-based think tank Brookings Institution. Speaking to RFE/RL’s Russian Service, Aleksashenko said if global oil prices rise, something few if any experts are now forecasting, then Russian economic growth in 2017 could be stronger. But Russia's economic prospects hinge not on possible government action but external factors.

And that’s because the government has failed to address the structural problems plaguing the Russian economy, explained Igor Nikolaev, the director of the Strategic Analysis Institute of the auditing and consulting firm FBK Grant Thorton. Among the factors holding back Russia’s economic are the country’s reliance on raw materials (commodity dependence), the relatively small role of medium and small business in the economy, and, vice versa, the large role of the federal government in it. Making matters worse are the Western sanctions slapped on Russia for its aggressive actions in Ukraine. Under such conditions, Nikolaev said, Russia can expect either marginal growth or even small dips downward.

Even amid the meager positive economic signs, the threat of Russia’s economy again heading south can’t be ruled out, said Valery Mironov, deputy director at the Development Center, a prominent Moscow-based think tank. Talking to RFE/RL, Mironov noted any significant draw down on Russia’s reserve funds (accumulated when oil was selling at more than $100 a barrel) would likely lead to budgetary cuts, sending fresh shockwaves thru an already vulnerable economy.

In fact, Nabiullina, despite speaking of a “new economic cycle,” has voiced little if any hope of the chances for significant economic growth. Speaking at a Moscow economic forum in 2016, Nabiullina said: “Regardless of the price of oil, even if it were $100, Russia cannot grow more than 1.5 or 2 percent [annually] without structural reforms and improving the investment climate.”

Oreshkin released his ministry's forecast on April 6 which forecasts 2 percent growth in 2017, but only 1.5 percent for the next three years till 2020. Those numbers correspond with Nabiullina's.

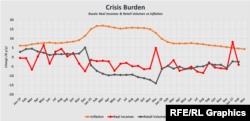

Any economic revival in Russia would first depend on reviving consumer demand, the “signs of demand reviving” that Nabiullina mentioned. Household consumption, which accounts for 52 percent of Russia’s GDP, shrank by 4.5 percent in 2016, according to Rosstat. This was the main factor in the economic slump. Moreover, the volume of retail trade services in Russia are still declining to last year’s levels. (Graph) Despite the recorded monthly growth of trade last fall, it has slowed down since. Taking account of seasonal and other factors, trade in Russia grew by 1.7 percent in January 2017, but only by 0.7 percent in February, noted experts at the Moscow-based Center for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short-Term Forecasting (CMASF) And it is hardly surprising given the sluggish growth in real wages (earnings adjusted for inflation). According to CMASF, real wages in Russia grew by a paltry 0.5 percent in January, but only by 0.2 percent in February. And this despite a significant slowdown in the rate of inflation.

And experts aren’t forecasting any significant pickup in real household incomes in Russia in 2017. In 2015, amid a devaluation of the ruble and high inflation in Russia, real incomes shrank by 4 percent and a further 5.9 percent in 2016, a significant two-year decline. CMASF predicts real income growth in 2017 in Russia at no more than 1.5-2 percent, said Igor Polyakov, a CMASF analyst, in an interview with RFE/RL. For 2018, CMASF is predicting 2.5 growth in real income. Getting incomes back to at least their 2014-levels, according to Polyakov, will take a least several years.

And if that is true, retail sales in the country can be expected to grow very slowly as well. CMASF forecasts retail sales growth in Russia to rise 2-2.5 percent in 2017 and 3-3.5 percent in 2018.By comparison, retail sales fell 10 percent just in 2015, the greatest drop in Russia in 60 years, noted Polyakov, and a further 5.2 percent in 2016. Just a few years back, the retail numbers were robust, exceeding 5 percent in 2011 and 2012.

At that time, rising consumption in Russia was fueled by rapidly rising wages, mainly in the public sector of the economy. Flush with cash amid peaking global energy prices, it was a policy Moscow at the time could afford. Those prices are long gone, but the problems in Russia’s economy have remained.

Wage growth in pre-crisis Russia clearly outpaced real economic growth, causing profits at companies to slump, noted Mikheil Khromov, head of the Financial Studies Department at the Gaidar Institute for Economic Policy.

“In other words, we ‘devour’ the majority of the country’s income in the form of salaries, instead of leaving them at companies and industries for investment in development,” Khromov told RFE/RL.

This factor, according to Khromov, is likely to continue in Russia in the coming years, restraining not only economic growth, but, paradoxically, salaries as well.

Tellingly, any acceleration in consumer demand is not expected in the short-term even by the Russian Central Bank, which Nabiullina heads.

“Consumer demand is recovering slowly and in spurts,” the bank stated in its latest review published on March 31. According to the report, the Central Bank expects total household consumption in the first quarter of 2017 to be 1-2 percent lower than for the same period a year earlier. Concurrently, the bank still expects private consumption to be higher than the October-December level.

Perhaps, similar expectations are what Nabiullina had in mind when speaking about “signs of reviving demand.”