Shortly after his deployment to Belgrade, the new Russian ambassador to Serbia, Aleksandr Botsan-Kharchenko, accused the European Union and the United States of exerting pressure on Serbia without considering the country’s best interests. He also falsely claimed that the U.S. and its allies are encouraging Kosovo to maintain tensions in the region.

“The constant pressure of the West on Serbia, exerted through the European Union, is evident, …while the U.S. and its allies are encouraging Kosovo to maintain tensions in the region,” Botsan-Kharchenko told Sputnik Serbia.

Botsan-Kharchenko said there is undoubtedly pressure on Serbia in its EU accession negotiations, while the Americans are pushing the country even harder to normalize relations with Kosovo before joining the EU. “Moreover, there is no evidence whatsoever that Belgrade’s best interests are taken into account in any form, in pursuit of a compromise solution,” said the Russian ambassador.

Botsan-Kharchenko’s accusations against the West are baseless, and related to Western criticism of the slow pace of Serbia’s EU accession negotiations, which he portrays as “pressure.” The second part of his claim concerns Belgrade’s refusal to recognize Kosovo as an independent state in order to join the EU.

Russian officials have routinely presented Kosovo as a “source of potential conflict,” and Western support for the independent state as a “destabilizing factor” in the Balkans. At the same time, Moscow is exploiting the strained relationship between Belgrade and Prishtina, and particularly Serbia’s refusal to recognize Kosovo’s independence, as one of the main tools of division and instability in the Balkans.

Moves by Kosovo to strengthen its sovereignty, including its efforts to create a national army, are promptly criticized by Moscow. Botsan-Kharchenko told Sputnik Serbia: “The West, and above all Washington, supports exclusively the Kosovo Albanians, their military structures and attempts to create an army, which are not only outside of the legal framework, but are also an obvious intention to increase tensions.”

The Russian ambassador’s claim that Kosovo’s intention to form its own national army is “outside of the legal framework,” is also false. Kosovo, which is recognized as a sovereign state by 102 out of 193 United Nations member states, is governed by its own constitution that permits Pristina to establish a defense ministry and an army.

The New Russian Ambassador

Botsan-Kharchenko is a diplomat with significant experience in the Balkans. He worked in the Russian embassy in Croatia in 1997-2002, served as Russia’s special envoy for the Balkans in 2004-2008, and Russia’s ambassador to Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2009-2014.

He was the Russian representative in the Kosovo Troika, a mediation group tasked to broker an agreement on the future status of Kosovo in 2007, that also included one representative from each the European Union and the United States.

Botsan-Kharchenko’s appointment as ambassador to Belgrade is viewed as a clear signal of Moscow’s intentions to maintain and potentially increase its influence in the Balkans. (Author’s interviews in Belgrade and Pristina in June 2019).

Russia's Special Balkans Representative, Aleksandr Botsan-Kharchenko, says Russia will not recognize Kosovo as an independent state if it declares independence unilaterally -- RT, February 5, 2008.

Serbia’s Slow EU Progress

Botsan-Kharchenko’s statements merely reinforce Belgrade’s position that Serbia needs “space” to make its own decisions regarding its European integration and relations with Kosovo. This refrain often serves as Belgrade’s excuse for stalling EU-brokered negotiations while pursuing the partition of Kosovo.

In claiming that the West is pressuring Serbia, the Russian ambassador omitted the fact that Belgrade has already made the strategic decision to apply for EU membership. In fact, the EU cannot invite potential members on its own initiative: the application process is initiated by the aspiring member state.

Once the accession negotiations are opened, there is immense work to harmonize the candidate country’s laws with those of the EU. This means complying with all 35 chapters of the acquis communautaire while implementing rapid reforms in governance, economy, trade, the judicial system, and so on. In other words, the government of the aspirant country needs to meet specific criteria to close each chapter while under pressure from their own publics to deliver on the promise of membership.

However, Serbia has been under no more pressure than any other EU candidate state during the last three decades. In fact, the EU has been less determined to pursue further enlargement following Brexit and the refugee crisis in Europe. Thus, there is much less pressure on EU candidates today than there was before.

Serbia became an EU candidate in March 2012 and started accession negotiations in January 2014. After five years of accession talks, the country has opened 16 chapters out of the total 35 and provisionally closed only two.

Belgrade’s progress has been much slower than that of other Central and Eastern European countries, which are already EU members. For example, Hungary, Poland, Estonia, the Czech Republic and Cyprus started negotiations in 1997 and became members only seven years later, in 2004. Bulgaria and Romania started the process in 1999 and joined the Union eight years later, in 2007.

Serbia is slated to join the EU in 2025, but many observers say that the reforms necessary to comply with EU requirements are not going to be completed on time. This would mean that all chapters must be closed by 2023, because of the long process of ratification in the European Parliament and the parliaments of all member states.

The latest report on Serbia’s progress toward EU membership also indicates that further delays are plausible. After five years of effort, the report points to only moderate preparedness in most areas. More importantly, the report calls for a genuine cross-party debate in order to forge a broad pro-European consensus, which is vital for the country’s movement on its EU path.

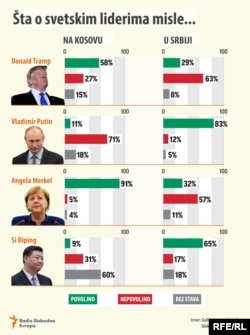

The pro-European consensus is precisely what Moscow is trying to undermine by opposing Belgrade’s potential recognition of Kosovo’s independence and emphasizing that the former autonomous region of Yugoslavia belongs to Serbia. (Author’s interviews in Belgrade and Pristina in June 2019).

The Kosovo Knot

The unresolved relations between Serbia and Kosovo have become an obstacle to Belgrade’s accession talks with the European Union. The Serbian political establishment has found itself in a difficult predicament: it wants to secure EU membership, but that is only possible if it signs an agreement with Prishtina recognizing the legitimacy of Kosovo as an independent state. At the same time, the potential agreement also needs to be acceptable to nationalist audiences at home that are adamantly against losing Kosovo.

The only way the government in Belgrade believes it can achieve both goals is a partition of Kosovo that would allow Serbia to annex its northern municipalities and thereby provide a way to justify some kind of recognition of the Kosovo state to the Serbian public.

However, Kosovo’s President Hashim Thaçi countered this possibility by insisting that a potential land swap must be reciprocal and include the Albanian-majority Preševo Valley in southern Serbia.

The controversial proposal for a territorial exchange was met largely with disapproval in both Serbia and Kosovo and elicited mixed reactions from EU and U.S. officials. While a potential peace agreement between Kosovo and Serbia -- with or without a land swap -- would increase the prospects for stability in the Balkans, it would also reduce Russia’s influence in the region. This is why the new Russian ambassador to Serbia criticized Western backing for Kosovo’s sovereignty and claimed that U.S. and NATO support for the budding Kosovo army encourages Prishtina to maintain tensions in the region. That claim is false.