Veiled heads in grey, white and black dotted the steps of Myeongdong Cathedral Monday night. Hushed voices spoke as one in prayer while evening commuters and shouting street vendors of Seoul rushed past in a blur.

Throughout Korea’s history, the cathedral has served as a refuge for society’s most vulnerable — from female workers of a textile company demanding equal treatment, to pro-democracy fugitives during Korea’s military dictatorship in the 1980s, and journalists fighting for press freedom.

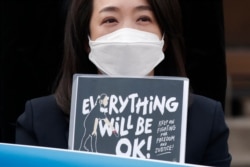

Today, people are again gathering in the same spot, but this time it's to demonstrate their support for Myanmar.

Each year on May 18, South Korea revisits transformative but painful memories of the bloody Gwangju Uprising, during which student activists protesting military rule were ruthlessly slaughtered in the southwestern city.

The nation marks the 41st anniversary of the pivotal demonstrations with a more pressing agenda this year: Koreans are reflecting on their own painful fight for democracy to offer support for Myanmar citizens experiencing a violent and relentless crackdown by the military that seized power in a February coup.

South Korean President Moon Jae-in condemned the suppression of civilian protests by Myanmar's military in a post on March 6, reaffirming South Korea’s solidarity with Myanmar “for a quick, peaceful restoration of democracy.” Gwangju Mayor Lee Yong-sup along with 17 mayors and governors representing all high-level local governments in South Korea have also demanded democracy be restored immediately.

Myanmar and South Korea, which formally established diplomatic ties in 1975, “experienced closely overlapping instances of political turbulence,” said Eunhui Eom, a research fellow specializing in Southeast Asian studies at the Seoul National University Asia Center.

On May 16, 1961, former South Korean dictator Park Chung-hee instigated a carefully devised military coup and overthrew the Second Republic — an event followed by the Burmese coup d'état just a year later that marked the beginning of socialist rule for 26 years.

But their paths eventually diverged when South Korea signed a treaty of mutual defense with the United States and transitioned from authoritarianism to democracy, while the military regime tightened its grip on Myanmar, previously known as Burma, under an isolated, socialist economy.

‘Visible violence’

It was only through word of mouth from older Burmese that Shun Lei Wutyee of Yangon learned about the so-called “8888” movement — the nationwide democracy uprising led by student activists who took to the streets on August 8, 1988, to protest the military regime under the ruthless dictatorship of Ne Win.

Now a college student studying digital communications in Seoul, 24-year-old Wutyee said that when she first read news of the Myanmar coup in the beginning of February, she thought it was baseless and things would quiet down in a few days. She had never seen bloodshed and thought this would end peacefully.

“But when someone died, I realized it was not a joke,” Wutyee said in Korean. “My generation has never been exposed to this kind of visible violence and it’s scary.”

Wutyee now stands in front of large groups, leveraging her fluent Korean to speak to people about what is happening in Myanmar, while also relearning her own country’s history.

This year, even amid the pandemic, organizers are holding events like art galleries featuring paintings by artists in Myanmar, weekly prayers open to the public, street protests in front of the Myanmar Embassy, recording songs and writing letters to raise funds or hosting seminars on democracy in Asia.

‘Road to fulfilling democracy’

Myanmar’s 8888 movement and the Gwangju Uprising were both animated by the bravery of young students at the forefront of the resistance, citizens angered by corruption who fought for their right to hold a fair election and unarmed civilian protesters who risked their lives.

Chun Doo-hwan, who was responsible for instigating the military coup in 1979 and enforcing the deadly crackdown on Gwangju protesters, was subsequently elected president of South Korea from 1980-1988. The military strongman eventually circumvented his death sentence and most recently made headlines for defaming a former democracy activist who survived the 1980s protests.

“At the time, Gwangju was painted as a failure,” said Professor Choi Jin-bong, who teaches political communications at Sungkonghoe University. “But history has unfolded to show that Korea’s road to fulfilling democracy would be incomplete without experiencing Gwangju. It’s why memories of the uprising are often summoned up as living proof of the people’s power.”

The 8888 uprisings were met with a similar fate — violently shut down by the military junta, leaving thousands dead. However, Wutyee said she believes the revolution is also what eventually fueled momentum for Aung San Suu Kyi to rise to power after a democratic landslide election victory.

“The more I learn about the resistance efforts of both Gwangju and Myanmar, I find the strength to continue organizing,” Wutyee said. “Sometimes I’m overcome by guilt while living in Korea because I don’t know if it’s okay for me to live well here while Myanmar people are suffering, but I’ve realized through this battle that I do, in fact, love my country.”

Despite the broader similarities Gwangju and Myanmar share, Eom said this comparison should not sweep over the sociohistorical circumstances specific to a country that many oversimplify the narrative.

“The solidarity we are seeing from Koreans has never been so fervent,” Eom said. “But Gwangju is only one dot we can connect Myanmar to. We can also look to the Philippines’ People Power Revolution in 1986 or the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests in China. Ultimately, Koreans must stand in the position of supporters, so that Myanmar citizens themselves can muster the strength to fight back and reclaim their narrative.”

Juhyun Lee contributed to this report.