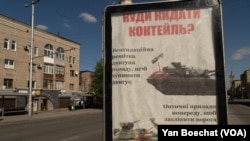

Billboards along the highway in Zaporizhzhia city say, “Russian warship go F*#@ yourself!” and “Put your Molotov cocktail here,” with drawings of red arrows pointing to sensitive spots on Russian tanks.

In the Zaporizhzhia countryside, wheat fields are nestled along the front lines and farmers wear body armor issued by the Ukrainian military as they work. The remnants of missiles are often found in these fields, farmers say, with recent attacks as close as next door.

“If the soldiers are the front line of this war, farmers are the second line,” said Vitaliy Lupynos, the owner of some 20 square kilometers of local farmland, where peas, barley, rapeseed and wheat grow. “We are feeding the country and the army.”

More than eight weeks into the war, Lupynos says, even a greatly reduced crop is not certain, with fewer than two months to harvest. In Zaporizhzhia Oblast, 85% of the farmland is now occupied by Russia and many farm workers remaining in Ukrainian-controlled lands have left the fields to join the army.

The region, one of Ukraine’s key food producers, usually generates an estimated 2.7 million tons of wheat. This year, farmers anticipate roughly 260,000 tons, if nothing else goes wrong.

But attacks in the city of Zaporizhzhia have become more frequent since Russia announced it would focus its efforts on eastern Ukraine after failing to take the capital, Kyiv. Farmers say they fear they could lose the entire oblast any day.

“We can’t tell what will happen tomorrow,” Lupynos said.

"It’s high stakes: like playing Russian roulette,” said Lupynos, referring to the deadly game of chance. "If Russian occupiers come here, they could take our lands. They could ruin the fields."

Hungry world

In recent months, food shortages resulting from the war in Ukraine have circled the globe, with price hikes of 20% to 50% for ordinary bread reported from Brazil to Pakistan and Egypt.

Ukraine and Russia are among the world’s most important food exporters, providing more than a quarter of the world’s wheat supply, along with other important crops such as corn, sunflower seed oil and barley.

The United Nations said the ongoing global food crisis is growing rapidly as a result of the war, with no sign it will slow down any time soon. The poor in many places are becoming destitute, and the hungry are starving. In vulnerable and war-torn countries like Yemen, Ethiopia and Afghanistan, the war in Ukraine has set off a chain of events that could lead to widescale famine as more than half the World Food Program’s (WFP’s) wheat supply comes from Ukraine alone.

“The bullets and bombs in Ukraine could take the global hunger crisis to levels beyond anything we’ve seen before,” said WFP Executive Director David Beasley in a statement last month.

Beyond hunger, the world now faces shortages of fuel, fertilizer and other farming necessities because of the war, and the U.N. has warned the growing scarcity could lead to civil unrest and increased global insecurity.

These warnings have done little to slow what appears to be pending disaster, according to Ukrainian officials. There is wheat in Ukraine waiting to be exported, but major ports are all closed due to attacks and most land routes are either unavailable or unsuitable.

“We are ready to sell,” said Olexandr Iasynytskyi, head of Zaporizhzhia’s regional agricultural department. “But we don’t have transportation. We are trying to figure it out.”

After the harvest

Even if they find a way to mitigate the crisis by getting this year’s harvest to market, Iasynytskyi said, next year’s harvest is already in greater danger.

While Ukraine’s exports are stuck in place, its limited expected crops should be enough to feed civilians and soldiers for the present, according to farmers and officials. Without export sales, they say, it’s not clear how they will be able to plant next season.

“Farmers do not have enough capital right now to invest in future crops,” said Iasynytskyi, the regional agriculture chief. “They have grain but they cannot sell it. How can they operate without money?”

Banks are offering limited loans, he added, but martial law has made lenders cautious and potential investors scatter.

Farms controlled by Russia within territorial Ukraine are expected to operate this year, but it’s not clear where the food will go, or how much there will be, Iasynytskyi said. It is believed the “occupied” farms are short of supplies and cash but information is limited as many areas under Russian control are without access to mobile networks or internet.

On the Ukrainian side of the war zone, farmers said if their plots are taken, they are not sure they will continue to work, for fear their crops will feed Russia’s war machine.

“I will never work for Russia,” said Roman Umarov, 30, an agricultural engineer overseeing the spread of insecticide on a Zaporizhzhia farm last week. “But I imagine it’s not always a choice. What if they put a gun to your head?”