This is Part Three of a five-part series on health care in South Africa’s Eastern Cape province

Continue to Parts: 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5

“My life has become small and empty compared to what it was like before,” said Nokuzola Ndabazonke. “I now only worry about the important stuff in my life – like hugging my baby,” she whispered.

Then she continued, laughing, “Even though I now only have one arm that works!”

Ndabazonke’s barely into her 20s but suffered a debilitating stroke a few months ago as a result of HIV infection and Tuberculosis Meningitis, or TB of the brain.

“My life has moved on; it now has meaning,” she insisted. “But I’ll never forget the day that stroke hit me. My whole body shook. Suddenly, the whole right side of my body was lame. I thought I was dying.”

Many people in this isolated part of South Africa, in Oliver Tambo District in Eastern Cape province, endure fates similar to Ndabazonke’s. The people here are so poor that they don’t have the money needed for transport to local hospitals. As a result, they receive treatment when it’s too late to save them from permanent disability, and sometimes even death.

Extremely high rates of HIV, TB and other highly infectious diseases combine with this to form an often fatal mix.

Ndabazonke now drags herself along on crutches. In the hilly, rocky and muddy terrain of the area, it’s a struggle for her just to visit a next-door neighbor. But she considers herself “very lucky.”

She commented, “A few months ago I could not walk and I could not speak. But then Laura helped me. She kept on telling me, ‘Keep on trying, keep on trying.’ If it wasn’t for her, I don’t know where I would be right now.”

Grateful patients

Physiotherapist Laura Grobicki smiled and clutched her patient’s twisted hands, massaging them. “It’s incredibly rewarding to hear someone like Nokuzola say, ‘You helped me,’ and to know that I’m one of only two physiotherapists available to 130,000 people in this region,” said Grobicki.

For most rural public hospitals in South Africa, some of which don’t have a single doctor, physiotherapists are luxuries. The facilities either can’t afford them, or the health professionals choose to work in the private sector or in developed countries where salaries are higher and working conditions much more favorable.

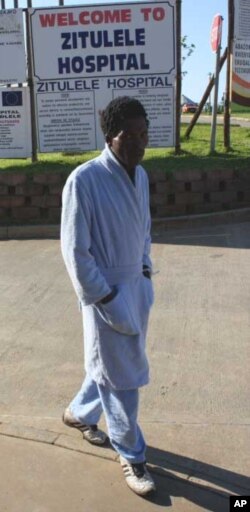

Grobicki, however, has made what she laughingly refers to as a “reverse journey.” After studying and working in Australia for several years, she recently returned to South Africa to work at Zithulele Hospital in Oliver Tambo District.

“I really enjoyed working in Australia and I enjoyed living there,” she told VOA. “But I felt like I was one of the many healthcare professionals there, in a well-run healthcare service. And I wanted to come back to South Africa which I loved and missed, and I wanted to work with people who I thought would need my skills more.”

Grobicki acknowledged that her life in one of South Africa’s poorest and most disease ravaged places is “much more difficult” but also “much more exciting,” adding that her patients – who she described as “amazing” – inspire her to survive.

“They wait many more hours than my patients in Australia, they get less time from me, and I can offer them less resources. Yet they’re often more grateful,” the therapist stated. “It keeps me going, when patients spend what little money they have on a visit to the hospital just to tell me, ‘You made me better; thank you!’”

‘I want to walk’

After her stroke, Ndabazonke spent three days in a hospital bed “basically just waiting to die,” she said.

Grobicki explained, “Hope is what so many of our patients struggle with. They can’t see through the prognosis of having HIV – a really bad infection, the medication (for which) just makes them feel really sick - and then on top of that, having a stroke.”

But the physiotherapist refused to allow Ndabazonke to sink into hopeless depression. “We did simple exercises in her bed; we did exercises that focused on specific muscle groups. Our first goal was for Nokuzola to stand up, and we achieved that within the first few days.”

Ndabazonke added, “When I stood for the first time by myself, it was a very big moment in my life. That’s when I wanted to carry on living. I had hope.”

Her patient’s next goal, said Grobicki, was to take a few unaided steps. “Then it was walking to the door of her room, and then it was walking outside; we progressed like that. So she now can walk really well with a crutch. She told me she can walk up and down hills in this area, which I think is no mean feat!”

With the help of a speech therapist, Ndabazonke is now able to talk again, albeit haltingly and hoarsely.

“She is talking beautifully; when we first met her she could hardly get even one or two words out, let alone a whole sentence,” said Grobicki. “Her first words (in Xhosa) were ‘Ndifuna hamba,’ which means ‘I want to walk.’ And whenever we walked into her room, that’s what she would say.”

She’s confident that Ndabazonke will soon be able to speak normally. “It’s just wonderful actually listening to her talk and being able to tell her story. And even though she can’t give her child a hug with both arms, she can still tell her child how much she loves her and give her a hug with one arm,” said Grobicki.

Arduous journey

But challenges, for both patient and therapist, remain. Ndabazonke’s right arm is paralyzed, and at this stage there’s not much hope of it gaining significant movement in the future.

“Instead of her right hand being the main hand she does things with, I’m showing her how to use it as a supportive hand, and the left hand will from now on be her main hand. But even doing little activities like that is a big challenge for her,” said Grobicki.

Antiretroviral medicines to treat her HIV and antibiotics to remedy TB helped to save Ndabazonke’s life. But, every month she must make a long and arduous journey in a wheelchair to a clinic to fetch her supplies of medication.

“It’s very difficult crossing this terrain in a wheelchair; someone else has to push her. In the mud, it becomes even more difficult, and up and down the hills and over the rocks,” Grobicki explained. “She needs to get to the road and then get into a taxi, and often they charge more for being a wheelchair user as well. Sometimes there aren’t any taxis and then she has to pay for a private vehicle, and that’s very expensive. Many of our patients are forced to do that.”

‘Heartbreaking’

Grobicki acknowledged that she sometimes feels “totally overwhelmed” at work in Oliver Tambo District, where tarred roads are rare.

“We can only help a fraction of the people here who need our help. It’s heartbreaking that because of minimal resources, we have to prioritize and choose some patients over others,” she said. “We have to make that decision on a daily basis, when we’ve got too many patients with not enough therapists to see them all and to meet the need that we know is there.”

When told about disabled people in the region who aren’t able to get to Zithulele Hospital, Grobicki often jumps into her car and tracks them down. She visits them in their homes.

“But there are even more that we know are out there that we can’t get to, and we know they can’t get to us,” she said, shaking her head while adding, “So when you feel on a daily basis that you’re not doing enough, it’s really encouraging to see someone (like Nokuzola) who says, ‘You know, that little bit that you did give to me has really changed my life.’”

Yet Grobicki acknowledged that in moments of desperation, she does sometimes yearn for her previous “life of comfort” as a physiotherapist in Perth, Western Australia, where she just had to snap her fingers for resources to be delivered to her office and where “everything was mechanical” and “orderly.”

But, when she returns to her consulting room, to witness other therapists celebrating another young disabled patient’s first steps, Grobicki said she knows in her heart that she’s where she belongs … In a place where her purse is much lighter than it was when she was on a far more developed side of the world, but where her spirit is “far richer” than it has ever been.