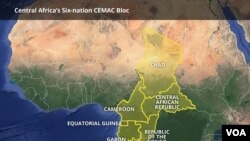

KIOSSI, CAMEROON — Analysts and businesspeople in the six-member Central African Economic and Monetary Community say that although the African Continental Free Trade Area launched in Niger last Sunday at an African Union summit brings hope for pan African trade, they are not sure CEMAC will be fully implemented anytime soon.

CEMAC's similar free-trade area has been plagued by corruption, national egos and a limitation of movement that have stunted the initiative.

For instance, the Cameroonian town of Kiossi shares borders with Gabon and Equatorial Guinea, and quite often, authorities in those two countries seal their borders without any comment.

Last December, Equatorial Guinea sealed its borders for a month. That same month, Gabon was expelling foreign citizens, especially Cameroonians, from its territory for what it called security reasons.

Puzzled by move

Gabonese-born Gabriel Ndongma, who buys building material from Cameroon and supplies for his country and Equatorial Guinea, said recently that he did not understand why the borders have to be sealed and people have to be chased away when central African states have a common monetary and economic community created to facilitate movement and trade.

He said CEMAC leaders should make strong political decisions that will make it possible for their people to travel freely among Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, Chad, Central African Republic, Cameroon and Congo, the members of the economic bloc.

CEMAC was created in 1994. All member states ratified the treaty creating it in 1999, and free movement of goods, services, capital and people was officially implemented in 2000. It has a population of about 45 million and covers 3 million square kilometers.

In 2017, CEMAC said it had reached a milestone after heads of state meeting in Chad lifted visa requirements for their citizens traveling within the bloc.

Chadian-born transporter Bismau Halidou said that besides the regular closure of borders by some states in the region, nontariff barriers have made it difficult for free interstate trade to take off.

Corruption problems

He said there were high levels of corruption among police, tax and customs officials in all central African states. He also noted that, surprisingly, Cameroon — which should pilot the integration process because it has a population of more than 25 million, more than half the region's total — was viewed as a country not to be trusted because of notorious corruption.

Daniel Ona Ondo, president of the CEMAC commission, said security challenges were making it difficult to ensure free movement that can deepen economic integration for its citizens. He said carnage has continued in CAR, Boko Haram terrorism has continued along Cameroon's northern border with Nigeria, and the separatist crisis has killed thousands in the English-speaking regions of Cameroon.

He said the region remains a place where pockets of tension and violence scare entrepreneurs away from investing or trading. He said it is still very difficult for people and goods to move freely because commuters are harassed by rebels and terrorists, and at times by security forces who are supposed to protect them.

Chadian-born Fatima Haram Acyl, CEMAC commissioner for trade and industry, said Central Africa is one of the poorest regions in the world, with 70 percent of the population living on less than $1 a day and 30 percent of the people going hungry. He said the people there see the African Continental Free Trade Area as providing a way to fight poverty. He also said the challenges faced by the region require that uncompetitive industries be developed or knocked out of the market by stiffer competition.

"We are going to have a big continental market in Africa, so it is very, very important for us to protect ourselves,” he said. “You know, when we have a big continental free trade area, there is going to be a lot of foreign products coming, so we have to protect our industries, we have to protect our people, we have to protect our market, because it is attractive for the whole world."

Much yet to do

Acyl said that despite the launch of the ACFTA, much work needs to be done before the agreement — signed by all 55 members of the African Union except Eritrea — becomes effective.

Trade between African countries has been held back by several bottlenecks, such as poor infrastructure, cumbersome border procedures, trade regulations, tariffs and the high cost of transactions.

The U.N. Economic Commission for Africa, however, estimates an increase in intra-African trade of 52.3 percent by 2020, asserting it will increase employment, facilitate better use of local resources for manufacturing and agriculture, and provide access to less expensive products.