The case of 5-year-old Kadijah Saccoh, who was raped and killed in June, allegedly by a family member in Sierra Leone, produced outrage and protests and escalated the debate about how to stop the crisis of rape and ongoing violence against women.

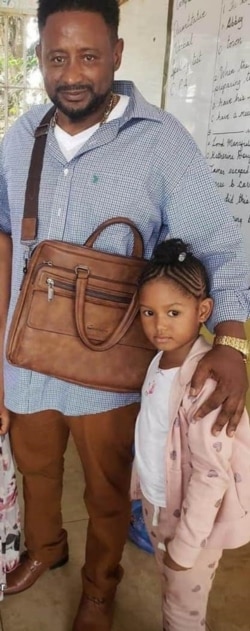

“My daughter’s story is very, very sad because in my country, rape has become acceptable in a family setting,” Kadijah’s father, Abubakarr Saccoh, told VOA via a Skype interview.

President Julius Maada Bio in 2019 declared rape and sexual violence a national emergency. At the time, the country had more than 8,500 reported cases of sexual and gender-based violence per year, but observers believe thousands of additional cases go unreported.

“Each month, hundreds of cases of rape and sexual assaults are being reported in this country. These despicable crimes of sexual violence are being committed against our women, children and even babies,” Bio said during a news conference in Freetown in February 2019. “Some of the fatalities are as young as 3 months old. Seventy percent of survivors of this traumatic experience are under the age [of] 15.”

Since then, the country has made strides, including strengthening its Sexual Offenses Act to allow for a maximum punishment of life in prison for someone who rapes a child. It also created a Sexual Offenses Division of the High Court to make sure sexual assault cases are prosecuted swiftly.

Still, advocates say the problem persists.

Numbers not falling

“There has been progress, but the numbers have not come down,” said Fatmata Sorie, a Sierra Leonean attorney and president of the group Legal Access Through Women Yearning for Equality Rights and Social Justice, also known as LAWYERS.

“One of the reasons why I think the numbers have not come down is because, quite honestly, the numbers came up — because more people were confident coming out to complain about these issues,” Sorie said. “Reporting increased, but the numbers have not increased insofar as successful prosecutions as against the number of claims that are being made.”

Since the declaration by the president, the country established a call center to report sexual crimes, but lawyers representing clients who have suffered gender-based violence (GBV) say the center also should be open for other forms of violence against girls and women, such as domestic abuse.

“We see that as a lost opportunity, because we want to move beyond the issues of rape and sexual penetration because women face much more violence,” Sorie added, speaking to VOA via Skype. “And we think this is an opportunity for the government to be able to document exactly the state of GBV in this country. So, we want that line to be open to all forms of violence against women.”

‘Discriminatory measure’

In March, the country made progress by overturning a ban on pregnant girls attending school or sitting for exams. The ban had been in place since 2010.

“We thought that it was a very discriminatory measure. It basically was, like, girls, they became pregnant and they were punished. They were sent out of school, while the boys, the men, that got them impregnated, they carry on with their normal life,” Marta Colomer Aguilera, West Africa’s Amnesty International representative, told VOA.

Aguilera added that the old argument for keeping pregnant girls out of school was deeply flawed.

“They decided that pregnant girls are not fit, are not mentally and physically capable of going to school when they are pregnant,” she said. “They also decided that pregnant girls are really a bad example for other girls. And that’s why they have to put them away.”

Thousands of miles away, Kadijah’s family struggles for answers.

Four people, including Kadijah’s cousin, who is suspected of committing the crime, have been detained, according to local reports. Her aunt, who was granted guardianship of the two girls; a teacher; and a maid are also in custody. If convicted of rape of a minor, the perpetrator could face life in prison following legislation introduced last year.

Father’s fight

In the midst of his anguish and grief, Kadijah’s father, who lives in Wilmington, Delaware, had to fight for his daughter to be given a proper medical examination before burial. He wants to make sure the person who is responsible is prosecuted.

“Please do not bury my daughter. If anybody buried my daughter, it’s going to be a problem,” Saccoh said, demanding to learn more about the cause of his daughter’s death.

Kadijah’s father was working to get his daughter to the U.S. before her tragic death. He told VOA as he broke down, overwhelmed by emotion, that he was planning to have her join him April 10.

“They have to test,” he said. “We have to find out what’s the cause of her death, because I just came from Africa and I saw them, you understand, and there was no issue with my daughter. So I don’t want [anybody] to bury my daughter. It’s a crime now, and I was able to stop [the burial].”

Esther Githui Ewart contributed to this report.