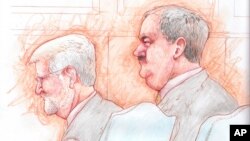

Surrounded by TV cameras outside a federal courthouse, former Massey Energy CEO Don Blankenship stood quietly and let his attorney do the talking after being convicted on a misdemeanor conspiracy charge in connection with the deadliest U.S. mine disaster in four decades. If found guilty of all charges, he could have been imprisoned for up to 30 years.

When a reporter asked for comment, the bullish coal baron — who once threatened to shoot a TV news journalist in his company's parking lot — only winked.

Just a wink, he was asked?

"Just a wink. A wink and a nod,'' he said, citing a phrase the defense used to challenge the conspiracy notion. Then he laughed and walked away.

The conviction in West Virginia on Thursday capped a five-year investigation into a painful chapter of Central Appalachian coal mining history. The massive effort proved complex and daunting for federal prosecutors, and yielded a fraction of what they sought.

Though U.S. Attorney Booth Goodwin asserted that his team may have made history by landing a conviction on a major company's CEO for workplace safety, Blankenship's misdemeanor fell far short of what prosecutors had hoped for.

William Taylor, the top lawyer on Blankenship's multimillion-dollar defense team, said he would appeal, but added that the defense wasn't as disappointed as it could have been.

University of Virginia law professor Brandon Garrett said the verdict shows jurors can hold a corporate chief accountable in a complex case.

"It was a challenge in a case like this to show that the CEO conspired to create the unsafe conditions within the mine,'' Garrett said.

Blankenship was convicted of conspiring to willfully violate mine safety and health standards, punishable by less than a year in prison. Jurors did not convict Blankenship of a more serious conspiracy charge to defraud federal mine safety regulators, which could have netted five years in prison.

Blankenship was also acquitted of making false statements and securities fraud about company safety after the deadly blast.

Barry Pollack, a white-collar defense attorney for Miller & Chevalier, said the outcome was "clearly a disappointment to the government,'' given its investment in the case.

"They were trying to hold Mr. Blankenship responsible for extremely serious felonies and while they obtained a conviction, it was only of a single misdemeanor count,'' said Pollack, who was not involved in the case.

For some relatives of the dead coal miners, the outcome was a victory of sorts, if not altogether just.

Judy Jones Petersen, whose brother Dean Jones was among the 29 men who died in the Upper Big Branch explosion, said she felt vindicated by the verdict and directed a scathing comment at Blankenship: "Although you may not be judged responsible by the courts of this land, you are guilty. The blood of these 29 people is on your hands.''

Four others lower in the Massey corporate chain served time for felony convictions as a result of the lengthy federal investigation that led to Blankenship's trial.

On Thursday, U.S. Secretary of Labor Thomas Perez stressed in a statement that the conviction sends a message: "No mine operator is above the law.''

Prosecutors said justice isn't measured only by the length of a prison sentence. Some other experts agreed, but say lawmakers should toughen penalties for breaking federal mine safety and health laws.

"They got a conviction on, to me, what was the most important count and the most important issue, that he conspired to violate mine safety laws,'' said Tony Oppegard, a mine safety advocate and Lexington attorney representing miners. "However, it's because of the weakness of the law, it's just a misdemeanor.''

"Frankly, that's one of the reasons historically there are very few people indicted after mining disasters. Prosecutors look to statutes that are felonies,'' Oppegard added. "It's just a fact of legal life, that's what they do. They're higher-profile cases if you can charge people with a felony. Therefore, there's been tons of cases over the years where individuals could have been criminally charged after a mining fatality and they haven't been.''

There's no question that mine safety laws should be strengthened, said U.S. Sen. Bob Casey, a Democrat from Pennsylvania.

"Putting the lives of workers at risk in unsafe mines should be a felony and I will continue to push to change the law so that those operating unsafe mines are held fully accountable,'' his statement said.

Juror Bill Rose, who spent all or part of 10 days mulling over the case with his peers, said jurors were struck by a particular detail in reaching the conspiracy conviction: when Blankenship told a subsidiary president, Christopher Blanchard, to start illegally mining a part of Upper Big Branch that was still filled with water. Blankenship then told Blanchard not to let the U.S. Mine Safety and Health Administration run his mines.

Rose said Blankenship's safety directives stirred reasonable doubt about the second and third counts, which charged Blankenship with lying to financial regulators and investors in a corporate press release that claimed Massey "strive[s]'' to meet safety standards and does not "condone'' violations. That statement pinned the claim on the corporation, not Blankenship as its leader.

"The charges on two and three were difficult to come to a conclusion,'' Rose said, because in the press release, the sentences including "strive and condone were worded perfectly to cover Massey as a whole.''

Near the now-shuttered Upper Big Branch Mine in the small community of Whitesville, retired coal miner Tim Bonds said Thursday that he had expected a mistrial.

Despite Blankenship's conviction, he said, "I don't ever expect him to do any time over it. I don't think he ever will.''