During my three-and-a-half year stint in South Asia, I have made five trips to the Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan.

In my six-nation area of responsibility only the Maldives, a nation composed of atolls, has a smaller population. Compared to India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Nepal, the other four countries I was tasked

with covering, Bhutan is an obscure and sleepy afterthought for most foreign correspondents.

But something kept drawing me back.

It was not only the serenity, cleanliness and the esoteric form of Buddhism practiced there.

It was also the attitude of its people.

Contrary to the modern image of Himalayan Buddhists, the Bhutanese had a reputation as warriors - fending off, centuries ago, Tibetan invaders. The Bhutanese strike visitors as friendly, although a bit restrained and superstitious. Sociologists will likely tell you the Bhutanese have a spiritual and protective psyche.

The Bhutanese have certainly done their best to carefully filter the demands and fashions of the modern world.

Modernity has gradually crept into Bhutan. It was the last nation to begin TV broadcasting, in 1999. And now nearly every Bhutanese I met in the capital, Thimphu, seems to be on Facebook. But traditional fashion still dictates dress: men go to work wearing the gho and women don the kira.

Bhutan, in recent years, has gained some outside attention for its unique concept of Gross National Happiness (GNH). This was a term coined by Bhutan's fourth King, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, in 1972 and meant as an alternative to the traditional measure of development, gross national product.

The small country of about 750,000 people is now taking GNH beyond an intellectual discourse and incorporating its values into its educational curriculum.

On several of my trips to Bhutan I sought to scrutinize this national state of happiness. Was it just a gimmick? Is it actually being implemented? Is it something the rest of the world should seriously explore? These were some of the questions I attempted to answer in my reports from Bhutan since 2007.

My most recent exploration took me to two places in Bhutan.

The first was the Changbangdu Primary School where classes begin with a moment of absolute silence. This is part of the new GNH curriculum Bhutan has introduced into its schools.

Teachers say they have already noticed a difference from the daily moments of meditation. Their students, they claim, are now more focused.

GNH also includes lessons on conservation and recycling. It also means teaching, for instance, why one should be considerate to other people. As a government policy, GNH, recognizes other components besides education, psychological well-being and ecology. They are: health, culture, living standards, proper use of time, community vitality and good governance.

Principal Dolma, who uses only one name, explains that Gross National Happiness is not only meant to be a classroom exercise.

"It's not just classroom teaching that we impart values," she explains in her office. "But the way a teacher speaks to the children, the way a teacher behaves with the children, so much so that even while we play games, value is imparted."

Bhutan's educators stress that happiness values, closely in line with the country's deep Buddhist faith, are not meant to bring religion into the classroom. But it is certainly not in conflict with those religious values.

That is what I found out when I visited the other important spot on my most recent Bhutanese journey - an old monastery difficult to find, up a winding side mountain road between the capital, Thimphu, and Paro.

At the Neyphug Monastery, established in 1550, the young head lama has set up a parochial school for some of Bhutan's most underprivileged children. They are learning similar GNH concepts although it is not called that there - rather it is part of the traditional Buddhist values taught to help attain enlightenment.

This is what they strive to achieve permanently, partly through leading a compassionate life, avoiding evil and eschewing material gain.

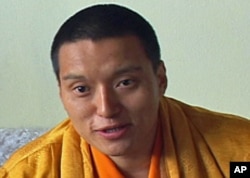

The 30-year-old chief monk and professor, Ngawang Sherdrup Chokyi Nyima, regarded as the 9th incarnation of the Neyphug Monastery's founder, sought to shed some light on the subject.

"In Buddhism, we call it enlightenment. People call it happiness. The happiness we have is very temporary, at the moment. But there is a day that you get this happiness permanently."

The trulku, which refers to an enlightened Tibetan Buddhist lama, added that the world's people should work on "the part of happiness in this degenerate time" by applying compassion, love and kindness.

The young professor, engrossed in his studies of traditional Tibetan Buddhism since he was a child in India and Bhutan, admits to not deeply understanding the nuances of the government's Gross National Happiness policy.

"I should really learn more about it," he acknowledges.

But even with my superficial understanding of GNH and Buddhism it is clear to me that the two are deeply intertwined.

I had initially become aware of this during a previous interview with one of Bhutan's senior monks, the Shinghkar Lama, Ngidup, who said he believed Bhutan was one of the few countries where the "very primary philosophy of Buddhism" has been put into practice and made a national goal. But how does one gauge the success of GNH in the method of metrics applied to Gross National Product, now better known as Gross Domestic Product or GDP?

The advice from the traditional experts, which will certainly befuddle economists: Do not get hung up on the numbers. The gauge for Gross National Happiness is probably abstract, explained the head monk of Shingkar.

"So whether you want to enjoy it in the forms of numbers or you can say like 'I'm having like 10 happiness' a day or something, I don't know. But as long as you're feeling peaceful that's how we want the measurement of feeling happy or peaceful or whatever," the Shingkar Lama told me.

The GNH concept is winning sympathy, if not endorsements, from those used to measuring development by the economists' measuring sticks. Talk to U.N. and World Bank experts these days who have spent their careers in the developing world and they will usually acknowledge that enormous growth is not equitable, creating new divisions that fuel further tension. The current upheaval, say in Thailand and Nepal, can be partly attributed to such disparities.

The good news for Bhutan is, that by any measuring stick, the country is gaining.

Sales of hydro-electric power to India means Bhutan's gross domestic product has been rising by double digits in recent years. On the U.N. Human Development Index, Bhutan - just a few decades ago considered one of the world's poorest countries with few schools or hospitals - continues to climb. In the 2009 rankings it is at 132, two spots ahead of its giant neighbor, India and closing in on South Africa.

That is enough to make anyone here smile.