This is Part 2 of a 5-part series: New Sounds of Africa

Continue to Parts: 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5

When Iain Robinson was eight years old in the late 1980s, he visited New York City with his parents. A few years earlier, the family had emigrated from South Africa to a small town in the United States.

“We were out sightseeing, and we came around a corner, and there were some guys break dancing in the street, for money. We gave them some crown (cash),” Robinson recalled.

Then, his parents led him to a nearby fast food joint, where they were soon joined by the break dancers. “We watched them count the money they had just made and buy themselves a meal. It really stuck in my memory as a young kid, watching this whole thing happen,” said Robinson. “Only now do I realize what a major influence that scene in New York has been on my life.”

It was his first “face to face” contact with the culture of hip hop. “It stayed in my brain and in my blood. And years later, it found me again,” the man who’s now one of South Africa’s eminent hip hop artists and rappers told VOA.

Fat and freckled white boy

In the early 1990s, the Robinsons returned to their home country. Apartheid was ending and political violence was sweeping South Africa, which was on the cusp of its first multiracial, democratic elections.

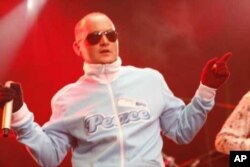

Iain Robinson himself was enduring the trauma of change – albeit that of a “normal, middle class” white boy. “In high school in Durban (on South Africa’s east coast in KwaZulu-Natal province) I was the fat kid with the curly hair, the glasses, the freckles and the American accent. So, bam! I couldn’t have been a bigger target,” he remembered.

His fellow students nicknamed him “Creampuff.” Robinson laughed, “In America, this is a pastry with a lot of cream and it’s generally associated with fat people.”

He was a hyperactive teenager, and he’d often “jump around” in class. One day, a teacher became frustrated with his bad behavior. “She looked at me and she said, ‘Look at you! You look like an Ewok!’”

Ewoks are rotund, furry, teddy bear-like creatures created by Hollywood film producer George Lucas for his Star Wars movies.

The teacher’s comment caused Robinson’s classmates to burst into laughter. “These guys were all going, ‘Creampuff; Ewok…Iain Robinson the Creamy Ewok! And that was my name through high school. I hated it. It was humiliating…”

‘Teddy bear hobbit’

But later in high school, when he got into hip hop, Robinson turned the hurtful teasing he suffered to his advantage. “I started thinking, “Yeah, that’s me. I’m Creamy! I’m a white kid rapping…” Instead of allowing the ‘Creamy Ewok’ insult to “break” him, he used it to “make” him.

“I really started to claim it. I really started to use it and say, ‘Yes, this is my name, what’s up,’ with that whole sort of ego and attitude that comes with hip hop. I was like, ‘Yeah, meet up, I’m emcee Creamy Ewok!”

Robinson added the “Baggends” part of his stage name in 2001. “When the Lord of the Rings movie came out, some people thought I looked like the hobbit character, Bilbo Baggins.… But I thought, ‘You can’t use ‘Baggins, that’s a hallowed name to some people.’ So I decided to spell my name differently.”

Rapping the truth

He acknowledged he initially “made a big mistake” by writing songs about subjects he knew nothing about. “I’m rhyming about blasting guns and nine millimeters because this is what I was hearing in the (American) rap that I loved! I thought, well, that’s what you’ve got to talk about if you’re going to be a rapper.”

But Robinson then “had a moment” in which he decided to take himself “more seriously. I said to myself, ‘Man, the last thing you ever want to be as an artist is caught out...talking about stuff you know nothing about.’” He explained, “You can’t rhyme about sex and loose women when you’re a married man and waiting for your first child.… You can’t rhyme about big cars and money…when you’re broke and your car is at the mechanics.”

Now, Robinson writes lyrics that are “true” in his life…About his personal experiences, social issues, his involvement in various anti-poverty and pro-democracy initiatives and what it’s like to be living in South Africa at this point in time.

In one of his recent songs, for example, he rails against corruption and political and corporate greed – huge issues currently in a country with a monumental disparity between a few rich people and millions of poor.

In “Shame on the Game,” Robinson raps, “The fat cats are fatter while the people seem lean.…The same ones who killed all our (anti-apartheid) prophets, my people, are the same ones pulling in the profits, my people.”

He also writes about the lighter side of life in his home country. In “Simmer in the City,” for example, Robinson rhymes over a jazzy beat about the intense summer heat in Durban.

He commented, “I can’t tell anybody what I’m going to write about tomorrow. But I’m going to tell you that it will be relevant, it will be associated with me and it will be truthful – one hundred and ten percent; I will never (expletive) you on the microphone.”

Creamy Ewok Baggends’s strongly South African rap has resonated around the world, and he’s constantly traveling to fulfill obligations at international hip hop festivals.

Inspiration from ‘Grandfather’ of hip hop

A constant presence in Robinson’s life is Afrika Bambaataa (born Kevin Donovan in the Bronx, New York)

Robinson explained, “I don’t know the dude for squat, but I admire him. The icon, the character that is Afrika Bambaataa, his story, inspires me.”

In the 1970s, the teenaged Kevin Donovan was a “warlord” in New York’s most feared street gang, the Black Spades. He was also a musician, influenced by various DJ styles emerging in New York at the time.

Then, Donovan underwent what he later referred to as two “life changing” experiences…Firstly, he watched Zulu, a film based on the South African ethnic group’s rebellion against the British colonial army in the early 1900s. Secondly, after winning a school essay competition, he visited a number of African countries.

Deeply moved by the poverty and humility, yet yearning for “freedom from oppression” he witnessed in Africa, and impressed by the Zulu people’s “honor and bravery,” he abandoned the gang culture. He dedicated himself to preventing youngsters from immersing themselves in gang violence.

Donovan formed the “Universal Zulu Nation,” blending principles of “knowledge,” “unity” and “peace” with the music he was making. He named himself “Afrika Bambaataa” after Zulu chief Bhambatha who’d led the insurrection against the British, and recruited many former gang members to his cause.

Bambaataa is credited with naming hip hop, a musical style that became a culture, combining the “break beat” music of DJs, the lyricism and poetry of emcees, break dancing and graffiti art.

‘Iconic vortex’

Robinson said, “I look at this man as this iconic vortex of amazing, positive, historical energy that’s touched millions of lives, including my own. I have so much respect and praise for the way that that man’s life and his energy have basically reached out and connected a whole global culture of kids.”

He remembered as a young man reading about Afrika Bambaataa “and finding out about his roots. I found myself going, ‘Yeah, (chief) Bhambatha - I know about that! I’m from Zululand.’ And then finding out about the Universal Zulu Nation, I started to feel a tangible pride that I was actually from Zululand…”

As a school kid, Robinson said he was a “history fanatic” and had on a number of occasions visited the place in the KwaZulu-Natal midlands where chief Bhambatha had started the Zulu “revolution” against the British – long before he knew anything about Afrika Bambaataa.

Then, a few years ago, another “Bhambatha link” surfaced in his life, when he met the woman who’s now his wife on the set of a theater show based on the life of the legendary Zulu chief.

“So (chief) Bhambatha keeps popping up in my life,” Robinson commented, adding, “I just trip out on the whole sort of romantic notion…that I am here with Bhambatha and he is here with me.”

He counted it as “highly significant” in his life and art that he became involved in hip hop in the same way that Afrika Bambaataa did – through Africa.

“People are always quick to say, ’Hip hop, this American thing, this black American thing and you are a white South African, (how can you be involved in hip hop)!’ But if we actually dig a little bit deeper and we look at the real story and we follow my story and we follow hip hop’s story – then we actually find out that we both come from the same place,” Robinson maintained.

‘New sound’ of South Africa

Just as Afrika Bambaataa motivated American musicians to “be authentic” and to use the language of the places they were from, namely “urban, ghetto America” in their art, said Robinson, so South African rappers have finally found their “true” voice.

He stated, “I think many South African artists are finally realizing that the world doesn’t want to hear Africans rapping like Americans; it wants to hear Africa.”

And so, explained Robinson, there’s “this massive growth” of vernacular rap in South Africa. “You’ve got stuff like zef – or ‘white trash’ – Afrikaans rap, you’ve got motswako, which is Tswana-based rap; you’ve got spaza, which is more of a Xhosa hip hop dialect. You get Afri-Kaaps, which is a colored (mixed race) dialect (from the Western Cape province). Here in Durban we have what we call a ‘gulley tongue’ that comes from the traditionally colored areas of Durban.”

He said South African hip hop artists are “staking their claim and saying, ‘this is the new sound (of South Africa), this is what we are all about, this is our culture expressed through our music.’”

Just as Robinson himself turned his humiliation as “Creamy Ewok” into triumph, so many South African musicians are now proudly using what they previously tried to escape – namely their “uneducated” dialects that highlighted their “lower class” roots.

“You could call this a trend but I think soon it’s going to be less of a trend and more of an entrenched value that’s going to serve us for years to come,” said Robinson. “It’s all about pride. My generation of South Africans isn’t ashamed of who we are anymore. We’re breaking the chains of our forefathers.”