With rates of online violence on the rise, a media foundation has developed a free tool to help shield journalists from harassment.

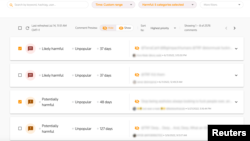

Created by the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the TRFilter identifies harmful or abusive comments made in English on a Twitter account, blurs the comments, and provides “toxicity scores” to help a user decide whether to view the posts.

It works “to protect your mental well-being, to protect or minimize your exposure to this barrage of toxicity,” Heba Kandil, a senior manager for media freedom at the Thomson Reuters Foundation, told VOA.

Research shows large percentages of female journalists experience online violence, and often struggle to find help in dealing with it.

The Reuters app offers features to address that, including the ability to create reports of harassment that can be shared with third parties such as newsroom editors or authorities.

Women affected disproportionately

It was developed with female journalists in mind, said Kandil, noting that they are affected by online violence at disproportionate rates.

A report released by UNESCO and the International Center for Journalists in 2021 found nearly 75% of the female journalists who responded to a survey had experienced digital harassment.

Media rights organizations say the attacks result in some women switching beats, refraining from covering certain stories, or even leaving the profession.

Lucy Westcott, emergencies director at the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists, said she felt unprepared for online harassment directed at her while working as a reporter at a news outlet in 2016.

Shortly after one of her stories was published, Westcott started to receive “very nasty language” in her Twitter mentions, as well as messages with photos of violent imagery.

Westcott told her editor and a senior colleague about the situation, and was advised to “lock [her] account.”

She deactivated it for about two months, during which the harassment finally died down.

Westcott called the harassment “emotionally devastating” and said it made her feel “extremely scared and very unprepared.”

“It made me want to completely disconnect with any kind of social media platform,” Westcott said. “To this day, I try to not spend much time on [social media] at all.”

The experience is one of the reasons she decided to work for the CPJ. The media rights group offers training and security advice on digital and physical attacks.

Minorities are targets

Beyond gender-based harassment, journalists of racial, sexual and religious minorities also face higher rates of online violence, research shows.

The joint UNESCO-ICFJ report found that over half of respondents who identify as Arab were victims of offline attacks associated with online violence, compared with 20% of all women respondents.

Social media can be a dangerous space for journalists because it makes them “more visible than they were previously, pre-internet,” said Jennifer Henrichsen.

The assistant professor at the Edward R. Murrow College of Communication at Washington State University is an expert in digital and physical threats to journalists.

Henrichsen pointed to a range of possible perpetrators, from everyday citizens to grass-roots collectives to state-sponsored actors.

“Maybe they are trying to discredit the journalist because they don’t like what that journalist happens to write about,” Henrichsen said. “Maybe they’re even just trying to slow down the journalist’s work or prevent the progress of their beat.”

Westcott of CPJ said harassment often is an attempt at “silencing” journalists.

Perpetrators aim “to intimidate [journalists], to basically make their lives extremely difficult so they will be dissuaded from reporting the news and reporting really important stories,” Westcott said.

'Promising tool'

Westcott has not used TRFilter app yet, but she described its ability to help manage online abuse as useful.

She said it aligns with some advice that CPJ often gives, which is for journalists in the middle of an online attack to hand their devices to friends or colleagues who can read through and report abusive comments.

Henrichsen called the TRFilter “a promising tool” for journalists, particularly its feature to create reports on abuse.

“It can kind of quarantine the hate, but [journalists] also have a repository — an archive of it — so that they can either share that with a platform, or they share that with a researcher ... or an editor,” Henrichsen said. “Somebody can then help develop a policy or another tool to remedy the situation.”

Henrichsen also pointed to other tools to address online violence, such as Block Party, which allows users to filter content and block accounts quickly.

Westcott stressed the importance for journalists to make sure that the least amount of personal information about them is publicly available. Tools such as DeleteMe can remove users’ personal information from leading search engines and data brokers.

Such tools are helpful, but media safety experts say that news organizations and social media platforms should be involved in addressing online harassment.

“The onus cannot be on the individual [journalist],” Kandil said. “It has to be a collective action.”

The Thomson Reuters Foundation partnered in 2021 with international institutes and law firms to develop several practical and legal guides to help newsrooms to protect journalists.

“Newsrooms have a responsibility to make sure there’s a plan in place before something happens, rather than scrambling after the fact,” Westcott said.

Twitter has previously outlined its work to address online hate on the platform.

In response to reports of high levels of violence on its site in June, Twitter told USA Today, "Hateful, abusive conduct has no place on our service, and we're focused on improving on our efforts here.”

Westcott acknowledged that Twitter took a helpful and important step in allowing users to limit replies to their tweets, but added, “There is definitely space for some more to be done.”