Kazakhstan’s long-time President Nursultan Nazarbayev relinquished power and stepped down on March 19, prompting speculation about this Central Asian country’s political future. But one question rarely asked is why Kazakhstan has not been the target of Russian disinformation campaigns. Since the absence of news is also news, we looked into this question to try and understand what motivates Moscow to launch disinformation against some countries and not others, particularly this one.

Vulnerabilities and Advantages

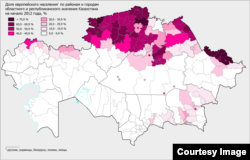

Three critical factors make Kazakhstan, the largest Central Asian country, acutely vulnerable to Russian pressure: the sizable Russian minority, representing one fifth of Kazakhstan’s population and concentrated mostly in the northern and eastern provinces; the long border with Russia, stretching 7,644 kilometers (4,749 miles); and the extensive economic connections between the two countries, including through the Eurasian Customs Union (ECU) and the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU).

However, there is also a number of elements that prevent Moscow from exercising decisive influence on Astana (now renamed Nur-Sultan after President Nazarbayev). These include Kazakhstan’s enormous size and vast energy resources; extensive Western investments in the energy sector and other industries; the country’s multi-vector foreign policy and rising international profile; its strong relations with Turkey and the Islamic world; its liberal policy on minorities and minority languages, including Russian; and Nazarbayev’s ability to keep Moscow at bay for the last 28 years.

The response of Russia’s media and policy community to Nazarbayev’s resignation was notably positive, almost warm. The program director of the Kremlin-supported discussion platform, the Valdai Club, Oleg Barabanov, said Russia’s partnership with Nazarbayev’s Kazakhstan could be considered “the optimal model for Russia’s bilateral relations in the post-Soviet space.” According to him, that relationship has far outgrown the level of simple Russian sponsorship, in contrast to a number of other examples. Barabanov praised Nazarbayev as “the founding father of modern Eurasian integration.”

Paris-based political analyst George Voloshin told Polygraph.info that Russia apparently was kept fully informed of the impending succession, including the choice of Kassym-Jomart Tokayev to be the new president. “By all accounts, it appears that the Putin administration views approvingly recent changes because they ensure continuity and the preservation of the strategic partnership with Moscow,” Voloshin said.

The strong bilateral ties between the two countries are one way to explain the absence of negative disinformation directed at Kazakhstan’s government or related to Nazarbayev’s personally. But Russia and Kazakhstan have not always agreed on a number of contentious matters over the years. In this respect, Nazarbayev has been able to stand his ground with Russia’s President Vladimir Putin (and, before that, with Boris Yeltsin) whenever Kazakhstan’s national interest and sovereignty were at stake.

The Crimea Factor

The most distinct example was Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, when Kazakhstan did not vote with Russia against the United Nations General Assembly resolution affirming the territorial integrity of Ukraine. Although Kazakhstan abstained, along with 57 other states, the signal resonated within Russia’s political circles and the media.

In annexing Crimea and staging a covert military intervention in eastern Ukraine, the Kremlin set a precedent by violating the 1994 Budapest Memorandum. This memorandum concerned not only Ukraine, but also Kazakhstan and Belarus. In 1994, Russia, the U.S. and U.K. provided security assurances for the territorial integrity and political independence of all three countries in exchange for surrendering their Soviet-era nuclear stockpiles.

The fact that Moscow justified its annexation of Crimea with the need to protect the rights and interests of the Russian and Russian-speaking populations on the peninsula sent a chilling message to Kazakhstan. The Russian minority in Kazakhstan, despite significant repatriation to Russia since 1991, still comprises more than 20 percent of the population. Most of Kazakhstan’s Russians are concentrated in the regions bordering Russia.

Multi-Vector Policy

“The geopolitics of Kazakhstan, with long borders with both Russia and China, mean that the Kazaks must balance,” Enders Wimbush, a Distinguished Senior Fellow at the Jamestown Foundation and former director of Radio Liberty, commented for Polygraph.info. “Kazakhstan has a ‘multi-vectored’ foreign policy, which means accommodating both Russian and Chinese interests, primarily. They have done this exceptionally well. They think strategically, unlike most other Central Asians, who don’t see the larger tapestry clearly.”

Balancing Russia and China, though, is only possible through maintaining strong relations with the West—with both Europe and the United States. Kazakhstan has done this remarkably well, too, through intensive diplomacy and attracting over $300 billion in foreign direct investment, mostly from Western countries like the Netherlands, the United States and Switzerland.

The first U.S. Ambassador to Kazakhstan, William Courtney, pointed out that Kazakhstan has a different strategy compared to other former Soviet states, but also fewer options as a land-locked country located far away from Western Europe. Kazakhstan is much more dependent on Russia than is Ukraine, for example, including for oil exports and trade. “The Kazakhs tend to be more pragmatic and more cooperative by temperament,” Ambassador Courtney told Polygraph.info. “Nazarbayev took advantage of these national qualities to develop a foreign policy strategy based on cooperation. He promoted tolerance and regional organizations that are important to Moscow, such as the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CST), the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU).”

Standing Up to Russia

At the same time, Kazakhstan’s leadership has successfully defended its national interests: it negotiated close to 100 tariff exceptions with Russia within the Customs Union and the EEU. President Nazarbayev even threatened to pull out of the union if it jeopardized Kazakhstan’s interests. In an interview with Khabar TV channel, he said: “Kazakhstan always reserves the right to leave the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) if it poses a threat to the country’s independence.”

The Kazakh president’s decision to switch the Kazakh language from the Cyrillic to the Latin alphabet caused controversy in Russia, Barabanov said. Nazarbayev first announced the government’s intention to introduce the Latin alphabet ten years ago, but waited for the state to build stronger institutions and a stable economy to withstand possible discontent among the Russian minority or Moscow’s potential opposition.

The plan was put into action in February 2018 and was met with resentment in Russia. On the one hand, the annexation of Crimea inevitably prompted Kazakhstan to press forward with policies enhancing the country’s Kazakh identity. On the other hand, Putin’s “Russian World” concept has heightened patriotic and imperial sentiments within Russia.

Since Crimea’s annexation, the Kremlin has put a special emphasis on preserving Russian historical monuments and Russian culture in the former Soviet countries, and the announcement of full transition to Latin script for the Kazakh language (due in 2025) rattled many people in Moscow. “Yet, Russian officials understand they can’t stop certain things from happening: direct interference is no longer an option as the examples of Georgia and Ukraine show,” said Voloshin.

Statehood Comment Debacle

Moreover, Putin learned a lesson from the public reaction in Kazakhstan to his August 2014 statement that, prior to Nazarbayev, “Kazakhs never had any statehood.” He credited Nazarbayev with creating “a state in a territory that had never had a state before.”

Kazakhstan’s reaction was overwhelming. Nazarbayev responded that the Kazakhs are the true and direct descendants of Huns, Göktürks, the Golden Horde and the Kazakh Khanate in Turkestan before the Russian conquest in the 19th century.

In 2015, Kazakhstan staged a large-scale celebration of 550 years of Kazakh statehood in the country’s capital, sending a clear message to Moscow that Kazakhstan would reject any disrespectful treatment.

Although some Russian nationalists continue to subscribe to Putin’s assertion that Kazakhstan belongs to the Russian world, the Kremlin backed off following the firm response to Putin’s blunder. Barabanov also admitted that Kazakhstan has only very rarely been the target of criticism from the political talk shows on Russia’s leading TV channels.

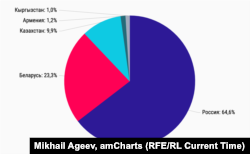

Moscow was apparently reminded of Kazakhstan’s paramount importance for Russia, as its only ally in the former Soviet Union that generally tolerates its policies—or, at least, does not vocally oppose them. By comparison, Voloshin said, “Belarus has always been a hard-to-handle partner due to recurring customs tariff and oil trade spats.”

It is also a key partner of Russia within the framework of the mega-projects in Eurasia. “We need to understand that without a partnership between Russia and Kazakhstan, no effective integration policy in Eurasia would be possible,” Barabanov wrote.

Russia’s weakness

But Wimbush stressed another development already affecting Moscow’s relations with Kazakhstan that will soon also become a decisive factor in Russia’s relations with other states: Russia’s weakness. (For more on Russia's weakness, see Wimbush's edited volume Russia in Decline)

“The Kazakhs know that Russia is failing. The Russians know that Russia is failing. The Chinese know that Russia is failing. So, the Kazakhs have little reason to push back on Russian influence, which, like the Russian ethnic population of Kazakhstan, will continue to decline,” Wimbush predicted.

Indeed, stirring the ire of the Kazakhs through disinformation would not be beneficial to vital Russian interests in this region; in fact, it could accelerate Kazakhstan’s realignment with China. “Unlike Ukraine, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova—all of which must calculate their strategic leverage and any visions of realignment on the reality of a fickle Europe and an uncertain U.S.—the Kazakhs actually have somewhere else to attach: China,” Wimbush said.

The Russian Bear and the Chinese Dragon

The record shows that Moscow usually employs disinformation when a state within its “designated sphere of influence” is trying to democratize, or join European institutions or NATO. It is generally believed that absent these preconditions, the Kremlin would not target a former Soviet state that is not prioritizing integration with the West. Still, Belarus has been on the receiving end of disinformation regardless of the state of its relations with the West, as have Kyrgyzstan and Armenia at times, although they have not been targeted as intensively as Georgia and Ukraine.

Is Moscow going to use disinformation against Kazakhstan if the process of “kazakhization” deepens and relations with China intensify? In other words, is potential Eastern integration going to trigger a disinformation campaign?

Wimbush believes China is over-reaching with the Belt and Road Initiative and will encounter setbacks and pushbacks. The Chinese are not necessarily welcomed as the potential dominant power in Central Asia: Kazakh officials say that they are familiar with the Russian bear and know how to deal with it, but the Chinese dragon is still unknown to them.

Eurasia’s Softening

Meanwhile, Eurasia is changing. A successful succession in Kazakhstan followed a smooth transition of power in Uzbekistan more than two years earlier. “Kazakhstan’s larger geopolitical universe includes a reform-minded Uzbekistan; a Turkmenistan that fancies some attachment to Europe; an Afghanistan-Pakistan conundrum that shows no signs of improving; and Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan that, while allowing some Russian influence, are increasingly resistant to it,” Wimbush noted. “This is to suggest to sensible Russians that their position in Eurasia generally has softened, probably to the point of being unable to retrieve a dominant presence.”

Finally, Wimbush stressed that the larger strategic universe is changing, with transformational realignments taking place almost everywhere around Russia—from Europe to Asia to the Middle East. Russia no longer shapes these processes. “If Kazakhstan slips from its universe and start moving toward China, the West, the Middle East, it will be an acknowledgement that Russia’s playing days are mostly over in its own backyard,” Wimbush stressed.

Disinformation Pass

So far, Russia’s disinformation networks have given Kazakhstan a pass. The reasons might be strategic or personal—Putin has always shown an unusual level of respect for Nazarbayev. Is this going to continue in the post-Nazarbayev era? The new president, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, is one of the most experienced Kazakh diplomats, intelligent and very thoughtful, according to William Courtney. He is trained in Chinese studies, served in the United Nations and dealt with his country’s human rights problems at the U.N. Human Rights Commission.

Tokayev will have to continue Nazarbayev’s legacy in security, foreign policy and economic development, but will also have to undertake long-overdue democratic reforms to ensure strong democratic institutions, political pluralism, and the peaceful transfer of power for many years to come. That could trigger Russia to turn on its transmitters and digital platforms to go after the Kazakh leadership, but it will also lead to Russia’s position in the region slipping.