Ten years ago corporate America was in turmoil, wracked by financial scandals at companies like Enron and WorldCom that drastically eroded public confidence in U.S. commerce. Congress reacted by passing the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, a law that forced change in corporate accounting practices and imposed stiff penalties on company officials who retaliate against whistleblowers.

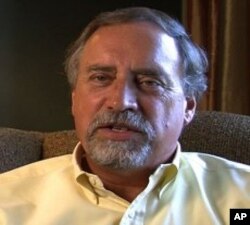

But according to Gordon Massie, who blew the whistle over wrongdoing at multinational insurance conglomerate American International Group (AIG), corporate situations are complicated and even legal experts do not always agree on what constitutes fraud.

Massie, who went on to write a memoir about his experience, had taken charge of several billion dollars of combined assets in 2001 when AIG merged with American General Corporation and soon discovered something was amiss.

"It was at that time that I became initially aware that AIG was not properly accounting for their own high-yield bond," he says, explaining that he tried to work from within the new company to fix the irregularities, but that it soon proved impossible.

"It was becoming apparent to me that fraud that was going on, that [what] I was dealing with was not a unique situation within that company, that there were accounting problems throughout the organization," he says.

Massie found himself marginalized within AIG and eventually left in 2005, as the company became the focus of several investigations ahead of its collapse a few years later. Last year he published The Whistleblower's Dilemma, his account of AIG's demise and his role in exposing the company's irregularities.

Now lecturing on corporate ethics and the difficulties employees face when confronting fraud, he argues that although people may want to do the right thing, even protective federal guidelines set forth by Sarbanes-Oxley aren't foolproof.

"Coming forward and revealing this information ... involves a significant amount of risk to anyone," he says. "Risk of retaliation, risk of job loss, maybe even risk of losing your career."

Although Sarbanes-Oxley offers protection to so-called whistleblowers, Robert Prentice, a business professor at the University of Texas, says the law is written to parse legitimate complaints and frivolous ones.

"The Sarbanes-Oxley law tried really hard to encourage whistleblowers, to reward whistleblowers, and to protect them from retaliation, but, at the same time, [discourage] cranks that are making complaints that are baseless," he says.

It's up to the companies, he says, to have a strong ethics codes that are taken seriously by employees and consistently enforced by corporate leaders.

And even then, Prentice says, whistleblowers inevitably must deal with conflicting emotions of wanting to be a loyal employee and an ethical team player.

Even for Massie, who suffered a bout of depression after losing his job and his career, that meant constantly grappling with the temptation to look the other way. It was only well after the federal government intervened and people began showing an interest in what he had done at AIG that his spirits began to lift.

"As I told my story after AIG blew up, I could tell it with a renewed sense of pride for what I had done and the decision I had made," he says, explaining that even in the complex financial world of today, an ethical stand made by one person can make a big difference.

"It is not enough to do nothing about it," he says. "It is not enough to put your head in the sand and think it is not your problem and allow the fraud to continue."