On May 4, 1961, 13 people took a ride that altered the course of the U.S. civil rights movement. Seven blacks and six whites, in two buses, headed for the Deep South to test a recent Supreme Court ruling that outlawed segregation in interstate transit. In Anniston, Alabama, a mob of about 1,000 white protesters firebombed one of the buses, then beat the civil rights activists. The incident angered and inspired many around the country. Hundreds decided to travel in integrated groups on buses and trains in the summer of 1961 in what came to be known as the "Freedom Rides".

"Breach of Peace" - a photo exhibit at the Skirball Center in Los Angeles - looks at the volunteers in this movement - the "Freedom Riders". Many were beaten by Southern police and angry mobs and hundreds were arrested.

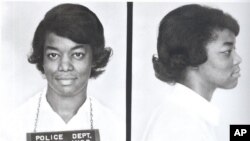

The Skirball exhibit tells the story of 40 freedom riders through interviews and contemporary portraits, along with their police photographs, or mug shots.

Eric Etheridge, the photographer who collected the images and interviews, published a book by the same name that includes 80 of the riders.

"The images are quite striking." said Eric Etheride. "They're sort of taken in the heat of battle, just after these people have been arrested."

The mug shot of protester Jorgia Siegel, a young white woman, is featured in the collection. She remembers what she felt as she saw the pictures on television that inspired her to join the movement.

"Just the revulsion at pulling people off a bus and then beating them with baseball bats and stuff like that - just horrifying. And it didn't seem like that kind of thing should be happening in my country."

Siegel rode buses from California to New Orleans, where she received training in nonviolent resistance before going to Jackson, Mississippi. There, she was arrested and briefly served time at the state's infamous Parchman Penitentiary.

Helen Singleton and her husband, Robert, are African American. Like many American blacks, they lived in the north, but had roots in the south. They also served time at Parchman Penitentiary in 1961 on charges of breach of peace.

Helen remembers the widespread racial restrictions as she was growing up, which she experienced on trips south to Virginia.

"And we couldn't stop anywhere along the way because none of the eating places would serve colored people back then. And that sort of stayed in my mind as something that had to be done just to get to grand mom's house."

Like his wife, Robert Singleton grew up in Philadelphia. Family vacations in the south also triggered a dilemma. His mother visited South Carolina for family reunions, but she would never bring her son.

"And she told me, many times, that I just didn't know how to act around white people who would feel superior to you and wonder why you didn't behave the way locals behaved under those circumstances. And she was right; I probably would have gotten in trouble."

Today, Singleton is an economics professor at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. When the freedom rides were starting in the early 1960s, he was already an activist and led a college branch of the civil rights group, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

"We were very active and this was the kind of thing we really wanted to do - to actually go south and do something that was more relevant than just sympathy demonstrations from afar."

While public transit systems were required to provide integrated service, they often did not. The freedom riders wanted to help desegregate those services. Many, like the Singletons, ended their trips in Jackson, Mississippi, where they were sent to the state's infamous Parchman Penitentiary on the charge of breaching the peace.

Helen Singleton notes that "breach of peace" referred to the riots that often ensued when the nonviolent freedom riders arrived in the South. And the term inspired the name of this exhibit.

Robert Singleton says the prison was frightening.

"They could push a button and your door would close. And when it closed with this clang, it shook everybody up, I guess, when they first got in there because it sounded so permanent. You realized there was no key."

The strategy of the Freedom Riders was to fill up the jails, overwhelming the system and bringing attention to their cause while furthering the broader civil rights movement. The strategy worked. By November, 1961, the U.S. Interstate Commerce Commission issued rules that prohibited segregated transportation facilities. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 went on to prohibit segregation in schools, public places and employment.

Many freedom riders featured in the "Breach of Peace" exhibition went on to finish school. Some continued their activism and they credit the freedom rides as an important influence in their lives.

Jorgia Siegel became a nurse after seeing how helpless she and other riders were to assist each other medically when some fell ill in prison.

She says, for southern riders, the rides were life-changing.

"Many of the African-American people that were from the South, their families lost their jobs. These people lost their livelihood; they lost everything. And many of those people were really young. They really did something. They really did something. For me, you know, fortunately nothing happened or anything. It's much different to go someplace else and do something. It's very hard to deal with the problems in your own area."

Robert Singleton says that years after the Freedom Rides, the election of the first black U.S. president, Barack Obama, inspired renewed reflection on the events of 1961.

"What we didn't know then, of course, was that almost the very day we were taken to Parchman Penitentiary, there was a child born on August 4, 1961 who would become president of the United States. He was the epitome of the very type of person we wanted to fight for. And when we think back about that, it justifies all the things we did and all the punishment we took in doing it."

And, years later, Helen Singleton's mother would tell a very different story of making the trip to Virginia and being welcomed by business on the way.

"My mother said, 'We went down to Virginia this year and we stopped along the way. My mother did live to see [the changes]. [She] lived to be able to go down [to Virginia without discrimination]."