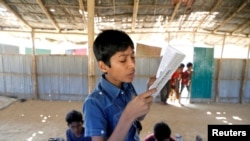

Dozens of sprawling informal education centers across refugee camps in Bangladesh’s Cox’s Bazar are providing a glimmer of hope for thousands of Rohingya refugee children who survived a massacre in their home country of Myanmar in 2017.

Across makeshift camps in refugee city of Kutupalong, hundreds of informal learning centers have been set up by international agencies and Rohingya community leaders to give the refugee children access to education. The opportunity to learn and improve skills is something the youngsters were never offered back in Myanmar.

Sharmeen Noor, a mathematics teacher at Kutupalong Primary School, told VOA that their programs ensure the Rohingya children do not fall behind in their education despite the absence of formal schooling. The centers can also create a positive impact to help those traumatized by the Burmese army’s 2017 crackdown that forced nearly 700,000 ethnic Rohingya to flee from Rakhine state to Bangladesh.

“Those who have seen violence think about it all the time,” said Noor. “They pay very little attention in class. As teachers, we are working on this matter. We are trying our best to bring them into normal life. God willing we will do it.”

About 350 Rohingya children are currently enrolled at Kutupalong Primary School, which provides basic informal education from preprimary through fifth grade. The children are taught subjects such as general science, mathematical, English, Burmese, and Bengali.

Noor said many of their teaching activities focus on play-based learning to provide education and at the same time give the children a chance to forget the daily struggles they face in the overcrowded camps. Particular attention is given to children who are mentally challenged.

“We put these children in between two good students so that the kids can follow their example ... It is challenging, all kids are not similar. To understand them we have to rely on their mental ability. We make a list of pupils who are behind. To bring them to a normal level, we try to provide something they like, such as games,” Noor added.

2017 Crackdown

More than 700,000 ethnic Rohingya people fled their homes in Rakhine province of neighboring Myanmar in the summer of 2017 due to a crackdown by Myanmar’s army and Buddhist militias. The UN has described the army's campaign in Rakhine province as "textbook ethnic cleansing", and has charged that the Rohingya people suffered killings, rape, and mass destruction of their homes by the army and Buddhist militias.

Most of those who fled to neighboring Bangladesh have been placed in Kutupalong, making it the largest refugee settlement complex in the world.

An estimated 400,000 of the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh are children. Human rights organizations say only one-third of them have access to education. Lack of basic services and health care have also put many children at the risk of malnutrition and infectious diseases.

In a December report, Human Rights Watch said authorities in Bangladesh were deliberately preventing aid groups from providing education in the camps and banning Rohingya children from enrolling in schools outside the camps.

“Bangladesh has made it clear that it doesn’t want the Rohingya to remain indefinitely, but depriving children of education just compounds the harm to the children and won’t resolve the refugees’ plight any faster,” said Bill Van Esveld, the watchdog’s associate children’s rights director.

“The government of Bangladesh saved countless lives by opening its borders and providing refuge to the Rohingya, but it needs to end its misguided policy of blocking education for Rohingya children,” he added.

Informal learning centers

The Bangladesh government, however, announced in January that it was working with the United Nations’ children agency UNICEF to provide formal education to the children. UNICEF described the move as “a major new phase” for education of the refugee children that initially targets 10,000 Rohingya students from grades six to nine and will later be expanded to other grades.

Through a program called the Learning Competency Framework and Approach, the UNICEF currently provides informal education to 220,000 Rohingya children between aged four to 14. An estimated 315,000 children and adults are getting education in over 3,200 learning centers supported by the UNICEF and other agencies.

Many Rohingya refugees, however, say the learning centers are not enough to empower their children and equip them with needed skills.

Religious studies

Across the camps, religious leaders have volunteered to provide religious teaching in mosques and makeshift centers known as Madrasas. The children in the Madrasas mainly focus on Islamic studies and Arabic.

Teacher Abdus Sobhan told VOA that 15 volunteer instructors were working with him at a Madrasa hosting 93 students. The children in his classes are taught to recite Quran and learn Arabic.

“It is important to teach children religion, so that they refrain from bad actions and devote themselves to God,” Sobhan told VOA.

Hafez Idris, another Rohingya teacher based in Kutupalong lambashia I2 B3 camp, is working with four other teachers to help orphaned kids learn how to recite the Quran. The learning center, Nurani Yetim Khana and Hafez Khana, hosts as many as 250 Rohingya orphans who are put into religious studies as well as math, Burmese and English.

“We don’t take any money from students or people from our block, but if anyone willingly wants to contribute, then we accept the money. We run this Madrasa to save our religion and to educate our young generation about religious studies,” he told VOA.

According to Hafiz Ullah, another teacher at Hafez Khana, by providing children with education, even if informal, the community hopes to preserve their culture from being lost after being uprooted from Rakhine state.

Ullah said it was essential that the children learn what their community went through in Myanmar, particularly because many of them grow up in camps with no memory of their homeland.

“Our situation was very bad. We could not even wear our religious dress, and we just came to Bangladesh with one lungi, one t-shirt, and a cap,” he told VOA.