Russia’s ambassador to the United States, Anatoly Antonov, was asked during last week’s Carnegie Endowment nuclear policy conference whether Russia would use nuclear weapons to prevail and win a conventional conflict that it was previously losing. Antonov categorically rejected such a notion, claiming it was a “fairy tale” and “lots of fake news.”

Speaking on March 11, the Russian ambassador stated: “There is no first strike concept in the Russian doctrine. There is a clear reference in our doctrine when and under which circumstances we can use our nuclear weapons: when there is an attack on the Russian Federation, when there is a threat for the existence of the Russian Federation as well as our allies.”

Ambassador Antonov further denied the view held by many Western experts that Moscow’s military doctrine includes an “escalate-to-deescalate” nuclear strategy. That strategy entails using a limited nuclear strike in response to a large-scale conventional attack that exceeds Russia’s defense capacity in order to prevent a conflict from further escalating.

Antonov advised the audience to read all Russian public documents on this issue. We did, and found his statements deceptive.

The current Russian military doctrine appears to allow a first-strike with nuclear weapons, even if Russia and/or its allies are threatened only by conventional weapons, not nuclear arms.

Article 27. “Russia reserves the right to use nuclear weapons in response to a use of nuclear or other weapons of mass destruction against it and (or) its allies, and in case of an aggression against it with conventional weapons that would put in danger the very existence of the state.”

The Defense One newsletter, for example, asserted that this provision in Russia’s military doctrine clearly allows for the first-use of nuclear weapons.

The text of article 27 is ambiguous at best, as it opens the door for interpretation of what constitutes a danger to the state and under which conditions Russia would launch nuclear weapons. Moscow habitually claims that the Russian state is endangered by Western policies. “Thus the doctrine is merely a data point, not hard evidence,” wrote Stephen Blank, a senior fellow at the American Foreign Policy Council.

According to Stefan Forss, a professor at the Finnish National Defense University, the Russian military doctrine is basically defensive, as its main goal is to avoid war with peer antagonists.

“However, if a war is unavoidable, things change immediately,” Forss told Polygraph.info. “Then Russia goes on the offensive. The grim lessons WW II and Operation Barbarossa are such that a similar course of events can never be allowed to happen again. War is to be waged outside the borders of the Fatherland.”

Most Western military analysts agree that there is a fundamental difference between what Russia says in its public documents and what it does to increase its nuclear arsenal. The country’s procurement and deployment prioritize nuclear weapons by a huge margin. Pentagon officials have reported that Russia is aggressively building up its nuclear forces and expected to deploy a total of 8,000 warheads by 2026. They will include both large strategic warheads and thousands of new low-yield and very low-yield warheads to support Moscow’s new doctrine of using nuclear arms early in a conflict.

Senior U.S. experts concluded in their 2017 report “A New Nuclear Review for a New Age,” that Russian nuclear doctrine has undergone fundamental changes since the end of the 1990s, with an increasing salience of nuclear weapons. Open-source reports and testimony by U.S. NATO officials indicate that Russia has developed an “escalate-to-deescalate” or, more accurately, an “escalate to win” nuclear strategy that includes the possibility of nuclear first use in regional and local conflicts in order to terminate a conflict on terms favorable to Russia.

Former U.S. Secretary of Defense James Mattis described the Russian nuclear doctrine as “escalate to victory and then deescalate.”

Stefan Forss cites the famous Russian nuclear weapon designer, Yuri Trutnev, who believes that the credibility of deterrence depends on an unbroken chain of functioning nuclear weapons, designed for the whole spectrum of war.

“Russia’s present massive investment in a whole range of traditional and unorthodox nuclear weapon systems is proof that Russia follows Trutnev’s thinking and advice in its massive nuclear build-up,” concludes Forss.

In a new book, Russia's Military Strategy and Doctrine, Trutnev is quoted that “a material basis means the weapon system defines the doctrine that exists in reality as opposed to the declared doctrine.”

Russia’s declared military doctrine may indeed differ substantially from the real doctrine, just as Moscow’s official statements in favor of nuclear non-proliferation appear at odds with its actions aimed at getting out of nuclear treaties. During last week’s Carnegie Endowment conference, Ambassador Antonov, who led the Russian delegation to the New START negotiations ten years ago, dealt a blow to this last remaining major nuclear non-proliferation agreement. He rejected the idea of broadening the treaty by including newly developed nuclear weapons and delivery systems. For Antonov that was a non-starter. He said the two sides had to stick with the provisions of the treaty. This means leaving out new Russian nuclear weapons such as the Poseidon nuclear-armed submarine drone, the Burevestnik nuclear-powered cruise missile, and new missiles.

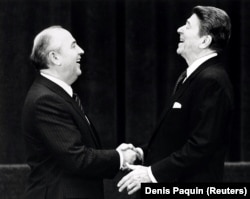

But Antonov is familiar with the changes in Russian nuclear policy since Vladimir Putin came to power. As Russia’s ambassador to the United Nations back in 2008, he strongly resisted introducing U.S. disarmament on the agenda of the UN Security Council’s Advisory Board on Disarmament Matters. Evidently, Russia had changed course and no longer followed the Gorbachev's vision of a world free of nuclear weapons.