Native American tribes and nations across the country say their members are murdered or go missing in alarming numbers, victims of domestic or drug-related violence, sexual assault or sex trafficking. And families of the victims say law enforcement is not doing enough about the problem.

Pinning down exact numbers is difficult. Individual states maintain databases on missing persons, but they don’t necessarily coordinate with one another.

The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) administers two national databases: the National Crime Information Center (NCIC), a central resource for reporting and tracking crime, including missing persons, and the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NamUs), a searchable, online database of information on missing persons and unidentified remains. As VOA learned, though, those systems are full of holes.

"If I threw a number to you, it would just be a number," said Janet Franson, a retired Florida homicide detective now living in Texas. She first noticed the problem several years ago while working for NamUs.

“I covered nine of the Northwestern states and more than 40 reservations,” Franson said. “And I started realizing that there were people going missing who weren’t even getting reported. In some cases, nobody even knew that they were gone.”

Today, Franson tracks missing and unidentified bodies of Native Americans and posts them on Facebook. Most of the cases she encounters are adults.

“When juveniles go missing, there’s a federal mandate that says law enforcement must file a missing person report and enter the child in the NCIC within two hours. But there is no mandate for adults," she said.

The system depends on families to notify police when relatives go missing. It also depends on police to fill out a missing person report.

“Sometimes police just don’t want to be bothered,” Franson said. Making matters worse, smaller reservations may not have access to NCIC computers and must rely on local or state police to do the reporting for them, as a courtesy.

Police indifference

At least two persons are currently missing from South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, home of the Oglala Lakota Sioux.

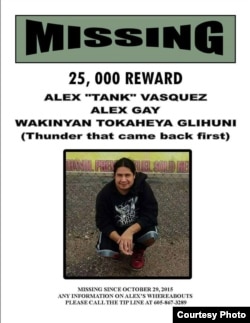

Alex “Tank” Vazquez, 26, disappeared in October 2015.

“I was on my way to Mexico on vacation when my other son called and said Alex hadn’t come home,” said Alex’s father, Mario Vazquez. “I didn’t think it was anything, but when I came back, I started seeing all the comments on Facebook, and then I started hearing rumors about him being killed by his cousins, about them killing him and feeding him to the pigs. I was going crazy.”

Vazquez filed a missing person report with the Oglala Sioux Tribe Department of Public Safety, which conducted air and land searches across the reservation. But that was two years ago, Mario Vazquez said. Since then, he said police don’t talk to him at all, and friends and family members have taken on the search for Alex themselves, circulating flyers, posting notices on Facebook and organizing search parties.

“It’s been a nightmare for me, and I don’t get any help from anybody. I just need to know what happened,” he said.

VOA heard similar complaints from the Navajo Nation, where at least 29 people are currently listed as missing, among them, 26-year-old Katczinski Ariel Begay.

“I last saw my daughter July 3 when she walked out of the door with her boyfriend,” said her mother, Jacqueline Begay. “The last thing I heard from her, she texted me and said she would be home later that evening. But she never came home.”

Witnesses claim to have seen Katczinski Begay getting into a Jeep parked outside a souvenir shop.

“The criminal investigator said she hasn’t even checked the store’s cameras yet. All she tells us is that she has a lot of other cases to handle and that she’s a single parent,” Jacqueline Begay said. And once police found out Katczinski Begay had addiction problems, she said police showed even less interest in the case.

“That’s a common problem,” said Meskee Yatsayte, a Navajo citizen who devotes a Facebook page to sharing information on missing tribal citizens. “As soon as you mention to police that the missing person likes to ‘party,’ they shove the case off to the side.”

Resources stretched thin

In fairness, Yatsayte said Navajo Nation police have limited resources.

“Right now, we have 134 police officers to cover 27,000 square miles [70,000 square kilometers]. Every officer has to patrol a 70-mile radius. And that means when somebody goes missing, it can take anywhere from two to nine hours to respond," Yatsayte said.

And this assumes that families have telephones or houses that are numbered, which many, particularly in remote corners of the reservation, are not.

“We really need a missing persons unit, someone who can concentrate to get these cases solved and get some answers for these families that are suffering every day,” she said.

Navajo Nation Police Captain Michael Henderson said his officers do their utmost to help families of the missing.

“If there is suspicion of criminal activity, police officers will do a preliminary investigation then turn it over to criminal investigators and the FBI,” Henderson said. “If there is no reason to suspect criminal activity or homicide, officers will take a report and enter it onto the NCIC database, as well as any DNA evidence they have, and conduct monthly follow-ups to see whether there’s any new information on the cases. They will continue until the missing person is found or they reach a complete dead end.

“But we are chronically undermanned to be able to do effective follow-up,” he admitted.

Currently, more than 200 police departments operate across Indian Country, which is defined as all land falling inside the limits of any reservations under the jurisdiction of the United States government.

The departments range in size from only two or three officers to more than 200 officers. And according to the California-based Tribal Law and Policy Institute, that’s about half the number needed to properly service tribal citizens.

The murder rate on Pine Ridge Reservation, for example, jumped 90 percent in 2016, but has a police force of only about 30 officers who must cover an area of about 3,400 square miles (8,800 square kilometers).

“Although cynicism, complacency and incompetence explain some of the reactions by law enforcement, the primary reason for this kind of response is a lack of resources, especially, personnel who are stretched too thin,” said Jeffrey Ross, a professor of criminology at the University of Baltimore and expert in justice in Indian Country.

Most tribal police departments are funded by the Interior Department’s Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), which is chronically underfunded.

Attorney General Jeff Sessions has acknowledged the “practical and jurisdictional challenges” facing tribal police.

“Law enforcement in Indian Country faces unique practical and jurisdictional challenges, and the Department of Justice [DOJ] is committed to working with them to provide greater access to technology, information and necessary enforcement,” Sessions said in April, announcing DOJ will expand tribal access to national criminal databases.

A new Indian Country Federal Law Enforcement Coordination Group comprising elements from a dozen federal agencies will convene to collaborate and coordinate efforts to counter crime on reservations. And he said the government will also conduct a series of listening sessions with tribal leaders and police in order to assess their needs.

But at the same time, the White House wants to cut about $30 million from federal programs that help tribes fight crime.

“The proposed budget cuts will have a devastating effect on the ability of tribal law enforcement to accomplish all of their interrelated goals, and not simply responding to missing persons reports,” Ross said.

And that leaves families with even less reason to hope.

“More and more missing persons cases are reported every day,” missing persons advocate Yatsayte said. “Eventually, they’ll simply end up as cold cases.”

Below, some of the many missing persons and unidentified remains in Indian Country:

NOTE: An earlier version of this story identified Janet Franson as working for the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children rather than NamUs. The story has been corrected.