Native Americans

For Native American Activists, the Kansas City Chiefs Have It All Wrong

Rhonda LeValdo is exhausted, but she's refusing to slow down. For the fourth time in five years, her hometown team and the focus of her decadeslong activism against the use of Native American imagery and references in sports is in the Super Bowl.

As the Kansas City Chiefs prepare for Sunday's big game, so does LeValdo. She and dozens of other Indigenous activists are in Las Vegas to protest and demand the team change its name and ditch its logo and rituals they say are offensive.

"I've spent so much of my personal time and money on this issue. I really hoped that our kids wouldn't have to deal with this," said LeValdo, who founded and leads a group called Not In Our Honor. "But here we go again."

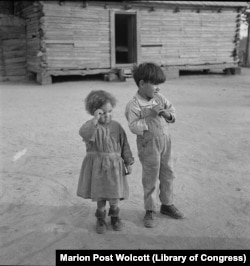

Her concern for children is founded. Research has shown the use of Native American imagery and stereotypes in sports have negative psychological effects on Native youth and encourage non-Native children to discriminate against them.

"There's no other group in this country subjected to this kind of cultural degradation," said Phil Gover, who founded a school dedicated to Native youth in Oklahoma City.

"It's demeaning. It tells Native kids that the rest of society, the only thing they ever care to know about you and your culture are these mocking minstrel shows," he said, adding that what non-Native children learn are stereotypes.

LeValdo, an Acoma Pueblo journalist and faculty member at Haskell Indian Nations University, has been in the Kansas City area for more than two decades.

She arrived from Nevada as a college student. In 2005, when Kansas City was playing Washington's football team, she and other Indigenous students organized around their anger at the offensive names and iconography used by both teams.

Some sports franchises made changes in the wake of the 2020 police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. The Washington team dropped its name, which is considered a racial slur, after calls dating back to the 1960s by Native advocates such as Suzan Harjo. In 2021, the Cleveland baseball team changed its name from the Indians to the Guardians.

Ahead of the 2020 season, the Chiefs barred fans from wearing headdresses or face paint referencing or appropriating Native American culture in Arrowhead Stadium, although some still have.

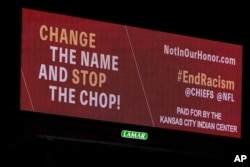

"End Racism" was written in the end zone. Players put decals on their helmets with similar slogans or names of Black people killed by police.

"We were like, 'Wow, you guys put this on the helmets and on the field, but look at your name and what you guys are doing,'" LeValdo said.

The next year, the Chiefs retired their mascot, a horse named Warpaint that a cheerleader would ride onto the field every time the team scored a touchdown. In the 1960s, a man wearing a headdress rode the horse.

The team's name and arrowhead logo remain, as does the "tomahawk chop," in which fans chant and swing a forearm up and down in a ritual that is not unique to the Chiefs.

The added attention on the team this season thanks to singer Taylor Swift's relationship with tight end Travis Kelce isn't lost on Indigenous activists. LeValdo said her fellow activists made a sign for this weekend reading, "Taylor Swift doesn't do the chop. Be like Taylor."

"We were watching. We were looking to see if she was going to do it. But she never did," LeValdo said.

The Chiefs say the team was named after Kansas City Mayor H. Roe Bartle, who was nicknamed "The Chief" and helped lure the franchise from Dallas in 1963.

They also say they have worked in recent years to eliminate offensive imagery.

"We've done more over the last seven years, I think, than any other team to raise awareness and educate ourselves," Chiefs President Mark Donovan said ahead of last year's Super Bowl.

The team has made a point to highlight two Indigenous players: long snapper James Winchester, a citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, and center Creed Humphrey, who is from the Citizen Potawatomi Nation of Oklahoma.

In 2014, the Chiefs launched the American Indian Community Working Group, which has Native Americans serving as advisers, to educate the team on issues facing the Indigenous population. As a result, Native American representatives have been featured at games, sometimes offering ceremonial blessings.

"The members of that working group weren't people that were involved in any of the organizations that actually serve Natives in Kansas City," said Gaylene Crouser, executive director of the Kansas City Indian Center, which provides health, welfare and cultural services to the Indigenous community. Crouser is among those who plan to protest in Las Vegas this weekend.

U.S. Representative Emanuel Cleaver, a Democrat, sees the label "Chief" as a term of endearment. He has been a Chiefs fan since he moved to Kansas City more than half a century ago, although he said it "wouldn't bother me that much" if the name were changed.

"A chief was somebody with enormous influence," said Cleaver, who is Black, making a reference to tribal chiefs in Africa. "As long as the name is not an insult or an invective, then I'm OK with it."

The story presented by the Chiefs features the message that the team is honoring Native culture. But Crouser calls that a "PR stunt."

"There's no honor in you painting your face and putting on a costume and cosplaying our culture," Crouser said. "The sheer entitlement of people outside our community telling us they're honoring us is so incredibly frustrating."

LeValdo is very conscious of who gets to own a narrative. As a University of Kansas journalism student in the early 2000s, she said a professor told her she would be too biased as a Native woman to report on stories about Native people. When she entered the world of video journalism, she was told she "didn't have the look" to be on camera.

During Chiefs home games, she and other Indigenous activists stand outside Arrowhead with signs saying, "Stop the Chop" and "This Does Not Honor Us." The sounds of a large drum and thousands of fans imitating a "war chant" as they swing their arms thunder from the stadium.

For LeValdo, the pain fueling her anger and activism is rooted in the oppression, killing and displacement of her ancestors and the lingering effects those injustices have on her community.

"We weren't even allowed to be Native American. We weren't allowed to practice our culture. We weren't allowed to wear our clothes," she said. "But it's OK for Kansas City fans to bang a drum, to wear a headdress and then to act like they're honoring us? That doesn't make sense."

See all News Updates of the Day

Native American news roundup, March 9-14, 2025

Tribes and students sue feds over staff cuts at BIE schools

Three Tribal Nations, along with five Native students, are suing the U.S. Interior Department and the Office of Indian Affairs over mass firings at the Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) and its federally operated schools — Haskell Indian Nations University in Kansas and Southwestern Indian Polytechnic Institute (SIPI) in New Mexico.

The layoffs stem from President Donald Trump’s February 11 executive order calling for broad cuts to federal staffing. Haskell lost more than a quarter of its staff, leaving courses without instructors, delaying financial aid and forcing students to clean dorms and restrooms. At SIPI, staff cuts led to 13-hour power outages, undrinkable tap water, and canceled midterm exams due to a shortage of faculty.

The lawsuit by the Native American Rights Fund representing the Pueblo of Isleta, the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation, and the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes argues that the layoffs violate federal law, which requires the government to consult with tribes on educational decisions impacting Native students.

“Despite having a treaty obligation to provide educational opportunities to tribal students, the federal government has long failed to offer adequate services,” said Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes Lieutenant Governor Hershel Gorham. “Just when the [BIE] was taking steps to fix the situation, these cuts undermined all those efforts.”

Read more:

Arizona tribes fear Trump’s English-only order could undermine tribal language revitalization

The Arizona Republic newspaper this week reports that Native Americans in that state worry that President Donald Trump's executive order declaring English as the U.S. official language could undermine efforts to revive and preserve Indigenous languages.

The March 5 order emphasizes that English has been the nation's language since its founding and that having one official language will “reinforce shared national values” and “create a more cohesive and efficient society.”

The order revokes a previous executive order that aimed to provide services for people with limited English proficiency, but it does not require any changes to services currently offered in other languages. It clarifies that agencies do not need to stop providing documents or services in languages other than English.

"It is taking a stance without really any teeth behind it," said Pima County recorder Gabriella Cázares-Kelly, a citizen of the Tohono O’odham Nation. "So, it's essentially saying this is optional for people, which is not how our government operates or should operate."

Federal laws, including the Native American Languages Act, support language instruction and protection, ensuring that Native peoples can continue to practice their languages without fear of punishment.

Read more:

Tribal groups accuse CSULB of stalling on Puvungna protection

Native American tribes are calling out California State University, Long Beach for failing to honor a 2021 settlement agreement to protect Puvungna, a sacred 22-acre site on campus. Despite promising to establish a conservation easement, the university has withdrawn its Request for Proposals without explanation and has provided no updates on its plans.

Tribal leaders, including Joyce Stanfield Perry of the Juaneño Band, say this delay echoes a long history of broken promises to Indigenous communities. Adding to their frustration, debris and soil dumped on the site in 2019 remain unremoved.

Puvungna, once part of 500 acres of Indigenous territory, is sacred to the Tongva, Acjachemen and other Indigenous tribes of Southern California. Tribes successfully stopped the university from building a mini mall on the land in 1993. The legal battle began in 2019 when the university dumped 4,900 cubic meters of construction debris on the site.

Tribal groups sued, and in a 2021 settlement, the university agreed to “make a good faith effort” within two years to clean up the site and permanently maintain it.

The university issued a Request for Proposal to find stewards for Puvungna. The Friends of Puvungna, an Indigenous-led nonprofit, submitted the sole proposal in collaboration with the Trust for Public Land. The university rejected that proposal, citing concerns over conflict of interest and a lack of demonstrated experience in land stewardship.

Read more:

Conservation groups, feds, tribes and ranchers clash over latest Yellowstone bison trapping

Wildlife advocates are sounding the alarm over Yellowstone National Park’s latest roundup of wild bison, which has seen more than 300 animals captured and sent to slaughter this month. Groups like Roam Free Nation argue that the practice is cruel and unnecessary, calling for greater protections and expanded roaming territory for America’s first national mammal.

Montana ranchers oppose expanding bison populations, arguing that the animals could spread brucellosis, a disease that can cause cattle to abort. Although no documented cases of transmission from bison to cattle exist, ranchers fear that even the chance of an outbreak could trigger costly quarantines and financial losses.

But many Native American tribes have treaty rights to hunt bison on their traditional lands, even outside reservations and advocate for expanding bison habitat, reducing government-led culling, and increasing tribal management of herds. Some tribes also push for co-management agreements with federal and state agencies to ensure bison populations are sustainably restored while respecting Indigenous cultural and spiritual connections to the animal.

Craig L. Falcon, a citizen of the Blackfeet Nation in Montana, has been hunting buffalo in Yellowstone for three decades.

“Our people really depend on it,” he told VOA. “Like myself, my freezer is pretty bare right now, and there are older people, older relatives of mine, including disabled Army vets, that need that meat, and I hunt for them.”

Read more:

Native American news roundup, March 2-8, 2025

IRS staff cuts leave tribes struggling for answers

Tribal advocacy groups are expressing outrage over job cuts at the U.S. Internal Revenue Service’s Office of Indian Tribal Governments (ITG), the agency that guides federally recognized tribes on tax matters.

As Tribal Business News reports, tribal governments are tax exempt, but there are some exceptions. With fewer specialists on hand, tribes now face potential delays, less access to tax guidance and a steep learning curve as they grapple with ever-evolving tax codes.

Legal experts warn that this staffing cut weakens tribal representation within the IRS, just as recent tax code updates introduce new exemptions and credit opportunities for tribal businesses.

“Tribes will have less access,” says Telly Meier, a former ITG director, echoing widespread concern that the office is now “overwhelmed.”

Democratic Senator Michael Bennet called the decision “absurd” and warned that it benefits wealthy tax cheats at the expense of tribal nations. Meanwhile, 14 tribal advocacy groups have demanded ITG staff reinstatement, emphasizing the federal government’s legal obligation to uphold tribal treaties and trust responsibilities.

Read more:

Full Senate to consider 25 bills on tribal issues

The Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, chaired by Republican Lisa Murkowski and co-chaired by Democrat Brian Schatz, this week approved 25 bills aimed at addressing key issues facing Native American communities.

The bills focus on tribal land restoration, water rights, public health, economic development and justice for Indigenous people who are missing or have been killed.

Murkowski highlighted her support for legislation enhancing tribal forest management, expanding veterinary services to combat diseases in Native villages, and creating a commission to address the lasting trauma of Indian boarding schools.

Schatz emphasized the importance of boosting Native-led tourism through the NATIVE Act to promote cultural preservation and economic growth.

Among the bills up for full Senate approval are:

S. 105, the Wounded Knee Massacre Memorial and Sacred Site Act, directs the secretary of the interior to complete all actions necessary to place 40 acres of tribally purchased land at the Wounded Knee Massacre site into restricted-fee status to be held by the Oglala Sioux Tribe and the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe.

S. 390, the Bridging Agency Data Gaps and Ensuring Safety (BADGES) for Native Communities Act, would support the recruitment and retention of Bureau of Indian Affairs law enforcement officers, boost federal missing persons resources and give tribes and states tools to combat violence.

S. 761, a bill which would establish the Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Polices to further investigate the history of Indian boarding schools and their long-term effects on Native American survivors and descendants.

See the full list of bills here:

Opinion: Returning federal lands to Native tribes a solution for better stewardship

Writing for Time magazine this week, Joe Whittle, a citizen of the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma, argues that giving federal public lands back to Native American tribes could help solve ongoing challenges in land management.

He holds that the Trump administration’s firing of thousands of federal land workers will have a severe impact on the environment and the way millions of Americans enjoy public lands and devastate local economies.

As a former backcountry wilderness ranger, Whittle believes Indigenous stewardship offers a stronger, more sustainable alternative, preventing corporate privatization while ensuring the public can still enjoy these lands.

His proposal aligns with the Land Back movement, which seeks to return land to Indigenous nations and apply traditional ecological knowledge — an approach based on taking only what is needed, preserving resources for future generations and maintaining ecological balance.

Whittle also suggests that long-standing treaty violations could be addressed by returning federal lands to Native tribes, offering a path toward justice while improving land management for all.

Read more:

UC tackles scholars’ false Indigenous claims

The University of California has launched an investigation into academics falsely claiming Native American heritage after several controversial cases emerged across multiple campuses.

UCLA professor Maylei Blackwell admitted her claimed Cherokee ancestry was false after allegations prompted research revealing her mother was white. Similar cases have surfaced at UC Riverside, Irvine, Berkeley and others of the UC system’s 10 campuses.

Critics say that so-called “pretendians’” false claims divert opportunities from authentic Native Americans and violate tribal sovereignty. As VOA reported previously, scholars who fake Native American identity often gain power to tell the public who Indigenous people are. Their publications can shape public understanding of Native communities and influence government policies affecting tribal members.

Read more:

Native American news roundup, Feb. 23-March 1, 2025

Julian Brave NoiseCat up for an Oscar at Sunday’s Academy Awards

Secwepemc citizens of the Williams Lake First Nation in British Columbia will gather at Academy Award watch parties Sunday as Julian Brave NoiseCat vies for an Oscar for the documentary “Sugarcane.”

NoiseCat, a citizen of the Secwepemc Nation's Canim Lake Band, co-directed the film alongside American journalist and filmmaker Emily Kassie. The documentary investigates unmarked graves at St. Joseph's Mission School, exposing harrowing evidence of systematic rape, torture and infanticide.

Through conversations with survivors, “Sugarcane” highlights the lasting impact of the residential school system.

"We stood alongside our participants as they dug graves for their friends, searched for painful truths in the recesses of their memories, and mustered the courage to confront representatives of the Church," the directors said in a statement. "You can feel their hesitation … as they struggle to confront their deepest secrets and give voice to their shame."

For NoiseCat, the story is deeply personal. His father, Ed Archie NoiseCat, was born at St. Joseph's and abandoned as an infant atop the school's incinerator.

In one of the film's most haunting moments, a former student recounts watching from a hiding place as a crying baby was tossed into the flames. Ed Archie NoiseCat is believed to be the only child fathered by a Catholic priest at the school who survived.

This nomination marks the first time an Indigenous North American filmmaker has been recognized in this category by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Read about the full investigation here:

ProPublica update on NAGPRA compliance shows progress, but much work remains

Museums, universities and other agencies across the United States returned to tribes the remains of more than 10,300 Native American ancestors in 2024, the investigative nonprofit ProPublica reported this week as part of its ongoing investigation into compliance with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, or NAGPRA.

Passed in 1990, the law requires all federal and federally funded institutions to inventory, report and repatriate all Native American human remains and culturally or spiritually significant artifacts.

NAGPRA previously allowed institutions to retain artifacts whose tribal affiliation they could not determine. Rules updated in 2024 removed that provision and gave tribal historians and religious leaders a greater voice in determining where those items should go.

ProPublica reports that 60% of indigenous ancestral remains subject to NAGPRA have so far been repatriated, but at least 90,000 remain in nationwide collections.

Read more:

Native Americans Severely Underrepresented in Medical School Admissions

STAT News highlights a 22% drop in American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) medical school enrollment last year: Out of 21,000 acceptances nationwide, 201 were indigenous.

Medical education leaders Dr. Donald Warne and Dr. Mary Owen express concern that indigenous physicians have remained less than 1% of all U.S. doctors for decades. At this rate, it would take more than a century for the number of Native American physicians to reach parity with their percentage of the overall population.

STAT reporting partly blames inflation, which has driven up medical school costs. The COVID pandemic had a disproportionate impact on Native communities, where limited broadband access meant many students were unable to study remotely.

Compounding matters is the 2023 Supreme Court ruling ending affirmative action in college enrollment. Leaders in Native American medical education emphasize that AI/AN is primarily a political classification for enrolled members of federally recognized tribes protected by treaty rights, so that they should not have been affected by the ruling against race-based admissions policies.

Read more:

Oklahoma tribe fights for control of former boarding school site in Kansas

The Shawnee Tribe wants ownership of the site of a former Native American boarding school, with Shawnee Chief Ben Barnes telling Kansas lawmakers that it was “built on Shawnee lands by Shawnee hands and using Shawnee funds.”

The Kansas Historical Society, the city of Fairway, and the local nonprofit that now runs the Shawnee Indian Manual Labor School all oppose the transfer, citing concerns over historical preservation.

The school opened in 1839 and included children from 22 tribes, mostly Shawnee and Delaware. Records show that at least five children died there in the 1850s. The school closed in 1862 and was later used as barracks for Union soldiers and as a stop on the Oregon, California and Santa Fe trails.

Read more:

Native American news roundup, Feb. 16-22, 2025

Native American tribes report federal funding delays

Some Native American tribes are having difficulties accessing funds for essential services following delays surrounding a temporary White House freeze on thousands of federal programs pending the new administration’s review.

Public Law 93-638, the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, is the vehicle through which tribes contract with the federal government to manage most health and education programs that were operated by the government before 1975.

While funds for 638 contracts are now unfrozen, some tribes reported having problems accessing the funding online.

"Tribal nations have candidly shared with me that at first, [online] funding portals were frozen. Even after they opened, funding requests went unanswered for days and weeks,” Sault Ste. Marie tribal council member Aaron Payment told VOA.

The former first vice president of the National Congress of American Indians said tribes remain uncertain about the stability of funding for community health, education and nutrition.

"As it is, we are far underfunded despite our having prepaid for every penny with the nearly 2 billion acres of land that made this country great," Payment said.

Read more:

Federal cuts force layoffs at Native American colleges

The Board of Regents of Haskell Indian Nations University is asking Interior Secretary Doug Burgum to waive staff reductions that would cut nearly 40 employees across teaching, IT and administrative departments.

“Haskell is an important part of the federal government’s commitment to enhancing the quality of life for Indian people,” the board’s letter reads in part.

Haskell in Kansas and Southwestern Indian Polytechnic Institute (SIPI) in New Mexico are both facing challenges in the new administration’s budget cuts, with Southwestern Indian Polytechnic losing 20 employees.

Those reductions leave 80 staff for 200 students at the New Mexico school and 125 staff for nearly 900 students at Haskell.

"It's affecting Native American students because at the end of the day, it's our generation of students who are going to be contributing to tomorrow's society," SIPI staff member Luke Gibson (Navajo) told Alburquerque's KOB TV. "If we don't invest in Native American education today, how will be useful to our own communities when we want to?"

While the Indian Health Service saw some layoffs temporarily reversed, there has been no similar relief for those universities. Haskell administrators told students that efforts are underway to maintain operations despite lower staffing.

Read more:

Supporters celebrate Leonard Peltier’s homecoming

Native American activist Leonard Peltier returned to the Turtle Mountain Reservation in Belcourt, North Dakota, Tuesday after 49 years in federal prison.

U.S. President Joe Biden commuted Peltier’s sentence last month in one of the last acts of his presidency.

“He is now 80 years old, suffers from severe health ailments, and has spent the majority of his life (nearly half a century) in prison,” Biden said in a January 20 statement. “This commutation will enable Mr. Peltier to spend his remaining days in home confinement but will not pardon him for his underlying crimes.”

Peltier, who is Anishinaabe and Dakota, was convicted of two counts of first-degree murder in the deaths of two federal agents during a 1975 standoff on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. He was given two consecutive life sentences.

Peltier supporters say he was framed. Federal law enforcement remains convinced of his guilt, with then-FBI Director Christopher Wray urging Biden “in the strongest terms possible” against granting Peltier clemency.

Read more:

South Dakota Senate says no to mandatory Native studies in public schools

South Dakota lawmakers have rejected a bill that would have required the state’s public schools to teach Native American content known as “Oceti Sakowin Essential Understandings.”

“Oceti Sakowin” translates as “People of Seven Council Fires,” an alliance of seven nations that were once known as the Great Sioux Nation.

The curriculum was developed over 10 years as a framework for cultural exchange in South Dakota, where Dakota, Lakota and Nakota tribes are spread out among nine reservations.

Currently, teaching Native American history is optional in South Dakota, with educators reporting that more than half of the state’s teachers already include it in their lesson plans.

Governor Larry Rhoden this week signed a bill requiring all certified teachers to take a course in South Dakota Native American studies.

Read more:

Trump backs Lumbee Tribe's long-standing quest for federal recognition

U.S. President Donald Trump wants Interior Secretary Doug Burgum to come up with a plan to grant the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina what he calls “long overdue” federal recognition, fulfilling a campaign promise he made last September.

Federal recognition acknowledges a tribe’s historic existence and its modern status as a “nation within a nation” entitled to govern itself and receive federal benefits, including health care, housing and education.

Historically, tribes were recognized through treaties or laws or presidential orders or court decisions. In 1978, the Department of the Interior standardized those procedures, allowing recognition through the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Congress or a federal court ruling.

Those standards require tribes to demonstrate continuous political autonomy since the 19th century, and members must document descendance from historical tribe members.

The process is time-consuming and expensive, often requiring assistance from historians, genealogists and attorneys. Historic records, if they ever existed, may be lost or destroyed.

The 1978 rules, updated in 1994, also state that tribes previously denied cannot reapply.

‘Gray eyes’

Over time, the Lumbee have been linked to several historic tribes, including the Cheraw, Tuscarora and even Siouan tribes.

“One tribal name or a single cultural origin is insufficient to explain Lumbee history, because Lumbee ancestors belonged to many of the dozens of nations that lived in a 44,000-square-mile territory,” writes Lumbee historian Malinda Maynor Lowery. “The names of these diverse communities varied depending on where the people lived and on what Europeans wrote down about them.”

In 1584, English explorer Arthur Barlowe noted that some Indian children on Roanoke Island had “very fine auburn and chestnut coloured hair.”

Three years later, England established a small colony on the island. The governor left for England to gather supplies. When he returned, no one was there. There were two clues: the word "CROATOAN" carved into a fence post and "CRO" on a tree. This gave rise to the theory that they had been taken in by Croatan Indians.

In the early 1700s, Hatteras Indians at Roanoke, as the Croatans were now called, told English explorer John Lawson that they descended from those vanished settlers. They also had “gray eyes,” which Lawson believed confirmed their mixed heritage.

“They tell us, that several of their ancestors were white people, and could talk in a book [read], as we do, the truth of which is confirmed by gray eyes being found frequently amongst these Indians, and no others,” Lawson wrote.

Enduring names

The 1790 federal Census recorded family names found among the Lumbee today and classified them as “all other free persons.”

In 1835, North Carolina banned voting in state elections for anyone who had a Black, mixed-race or biracial ancestor within the past four generations, and the state amended its constitution to segregate Black and white children into separate public schools.

“As the lines between ‘white’ and ‘colored’ hardened in North Carolina … Indians resolved that non-Indians must recognize their distinct identity,” Lowery wrote.

In 1885, North Carolina recognized the Lumbee as “Croatan” Indians and created separate schools for them. Shortly after, 54 members identifying themselves as Croatan Indians and “remnants” of the lost colony petitioned Congress for aid to educate more than 1,100 of the tribe’s children.

The Indian Affairs commissioner turned them down, saying he could barely afford to support the tribes already recognized, let alone the Croatans.

The tribe renamed itself “Lumbee,” after the nearby Lumber River, in 1952. In 1956, Congress passed Public Law 570, acknowledging the tribe as a mix of colonial and coastal-Indian blood but denying them federal benefits.

In the 1990s, the Interior Department again rejected the Lumbee’s petition, citing insufficient proof of cultural, political or genealogical ties to a specific historic tribe. Despite failed bills, the House passed the Lumbee Fairness Act in December 2024, which, if approved by the Senate, would grant federal recognition and benefits.

The Interior Department released an update to the acknowledgment process, allowing certain tribes that were previously denied the opportunity to reapply for recognition. That was set to take effect this week but has been postponed to March 21.

Congress 'not equipped'

North Carolina’s federally recognized Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI) has long opposed Lumbee recognition.

“The Lumbee cannot even specify which historical tribe they descend from, and recent research has underscored the dangers of legislative recognition without proper verification,” EBCI principal chief Michell Hicks said in a December 2024 statement. “Allowing this bill [the Lumbee Fairness Act] to pass would harm tribal nations across the country by creating a shortcut to recognition that diminishes the sacrifices of tribes who have fought for years to protect their identity.”

Former EBCI chief Richard Sneed told VOA in 2022, “Congress is not equipped to do the necessary research to determine whether or not a group is a historic tribe or not. The process was created for that purpose.”

In an emailed statement, Lumbee tribal chairman John L. Lowery expressed cautious optimism that the Lumbee Fairness Act would pass.

“Our critics are sad individuals who use racist propaganda to discredit us while ignoring the struggles of other minorities in America,” he told VOA. “As Indigenous people, we are the minority of the minority here in the United States, and our critics are trying to erase the memories of our ancestors, and we will not let that happen!”

Fifty-six thousand people identified as Lumbee in the 2020 U.S. Census. If recognized, they would be the largest acknowledged tribe east of the Mississippi River.

Native American news roundup, Feb. 2-8, 2025

Native American groups this week expressed concern that some of U.S. President Donald Trump’s executive orders could challenge tribal sovereignty and Native citizenship.

Executive orders signed on Jan. 20 crack down on illegal immigration to the U.S. and mobilize federal law enforcement agencies and the U.S. military to stop, question and detain undocumented immigrants to achieve “complete control” of the southern border.

Navajo spokesperson Crystaline Curley told CNN that tribal citizens were being caught up in immigration sweeps, although she did not give a number. A Navajo citizen reported she had been questioned during an office raid in Scottsdale, Arizona, but was released after presenting her Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood.

Border czar Tom Homan told reporters Thursday that immigration enforcement operations are now focusing on criminal migrants, but “as the aperture opens up beyond criminals, you are going to see more arrests. I’ve made it clear: If you are in the country illegally, you are not off the table.”

In a statement to Newsweek, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement said its agents may encounter U.S. citizens during raids and will request identification to confirm their identities.

Tribes nationwide are encouraging members to carry tribal identification cards and Certificates of Degree of Indian Blood, which are issued by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and document a person's degree of Indian ancestry within a specific federally recognized tribe.

Some Natives worry US citizenship under federal scrutiny

A federal judge in Seattle, Washington, in January blocked Trump’s executive order denying automatic U.S. citizenship to babies born after Feb. 19, 2025, unless they have at least one parent who is either a U.S. citizen or lawful permanent resident. The order was paused indefinitely this week by a federal judge in Maryland.

That case was closely watched by Native Americans because U.S. Justice Department lawyers cited the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which excluded "Indians not taxed" from citizenship, and an 1880 Supreme Court decision that Native Americans were not birthright citizens. That 1880 decision centered on a Native American man in Nebraska who the court ruled owed allegiance to his tribe and was not a birthright citizen with the right to vote.

The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 granted citizenship to all Native Americans born in the United States.

Native groups, fearing funding freeze, remind White House of its federal obligations

Native American tribal groups wrote the new president about actions that could freeze or mislabel tribal funding.

“Our unique political and legal relationship with the United States is rooted in our inherent sovereignty and recognized in the U.S. Constitution, in treaties, and is carried out by many federal laws and policies,” the Feb. 2 letter reads.

The letter calls on the Trump administration to respect tribal nations as political entities, continue direct consultations, ensure federal workforce changes don’t disrupt services and keep tribal-focused offices in federal agencies.

It specifically warns against treating tribal programs as general diversity or environmental initiatives and invites government officials and Congress to discuss these issues further.

Interior secretary Burgum sworn in, stresses commitment to tribes

Doug Burgum was sworn in as secretary of the Interior Department on Jan. 31. He thanked Trump and stressed his history of working with Native American tribes during his tenure as North Dakota governor.

“In North Dakota, we share geography with five sovereign tribal nations. The current partnership is historically strong because we prioritized tribal engagement through mutual respect, open communication, collaboration and a sincere willingness to listen,” Burgum said. “At Interior, we will strengthen our commitment to enhancing the quality of life, promoting economic opportunities and empowering our tribal partners through those principles.”

Burgum has the support of several tribal leaders, including Mark N. Fox, who chairs the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation in North Dakota; Chuck Hoskin Jr., principal chief of the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma; and Bobby Gonzalez, chair of the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma.

Burgum on Monday hit the ground running with a series of orders advancing Trump’s energy agenda.

Secretarial order 3417 directs all Department of the Interior bureaus and offices to create a 15-day plan detailing how they can speed up energy resource development, from initial identification through production, transportation and export. The directive pays special attention to federal lands, the Outer Continental Shelf and specific regions that include the West Coast, Northeast and Alaska.

Secretarial Order 3418 calls for a 15-day review of public lands that the Biden administration withdrew from resource extraction, including national monuments of historic, cultural and spiritual importance to tribes.

“Among the sites most at risk are Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monuments in Utah,” Indian Country Today reported this week, noting that Grand Staircase-Escalante holds large coal reserves, and the Bears Ears area has uranium.

Read more:

Navajo nominated as DOI Indian Affairs Secretary

The National Congress of American Indians this week supported the White House nomination of Navajo citizen William “Billy” Kirkland III to serve as the Interior Department’s assistant secretary of Indian Affairs. If confirmed, he would head the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

"NCAI looks forward to engaging with Kirkland upon his confirmation to protect and further strengthen the government-to-government relationship and advance policy priorities that support Tribal Nations," said a statement from NCAI President Mark Macarro. "We remain committed to working in partnership with the Department of the Interior to uphold tribal sovereignty."

Native American media note that the nomination, as cited in the Congressional Record, lists the position as “Assistant Secretary of the Interior vice [“in place of”] Bryan Todd Newland, resigned."

Previously, the position was called “Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs.”

Kirkland’s nomination has been referred to the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs.

Read more:

Defense Department: Identity months ‘erode camaraderie’

The U.S. Defense Department this week issued a policy banning the use of official resources or work hours to host cultural heritage celebrations. These include National American Indian Heritage Month and Asian American and Pacific Islander Month.

“Our unity and purpose are instrumental to meeting the Department's warfighting mission,” the directive reads. “Efforts to divide the force — to put one group ahead of another — erode camaraderie and threaten mission execution.”

While official events are no longer permitted during work hours, service members may still attend such events unofficially during their personal time.

“We are proud of our warriors and their history, but we will focus on the character of their service instead of their immutable characteristics,” the new policy states.

Read the directive here:

Native American news roundup, Jan. 19-25, 2025

Senate Energy Committee approves Trump's pick to lead Department of Interior

The Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee this week voted 18-2 to approve the nomination of North Dakota Governor Doug Burgum to head the as U.S. Department of Interior.

If the full Senate approves, Burgum will oversee 11 bureaus and agencies that manage public lands, minerals, national parks and wildlife refuges. He will also oversee federal trust responsibilities to Indian tribes and Native Alaskans.

During his confirmation hearing, Burgum stressed that he has the support of his state’s five tribes.

“State and tribal relationships in North Dakota have sometimes been challenged, but the current partnership is historically strong because we prioritize tribal engagement through mutual respect,” Burgum told senators.

In addition to the Interior Department, President Donald Trump wants Burgum to lead a new national energy council.

Burgum has said he backs bypassing certain environmental regulations to increase energy production, create jobs and enhance national security. He also stressed his commitment to land conservation.

“We always want to prioritize those areas that have the most resource opportunity for America with the least impact on lands that are important, and I think that’s a pretty simple formula to be able to figure out,” Burgum said during his hearing.

Trump Pursues Recognition for Lumbee Tribe

Fulfilling a campaign promise he made to the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina last September, President Donald Trump this week directed the interior secretary to initiate steps toward securing full federal recognition for the tribe.

Historically, the tribe has been known by several names, including Tuscarora, Croatan, Cheraw and Cherokee. In 1953, it changed its name from "Cherokee Indians of Robeson County" to the "Lumbee Indians of North Carolina."

North Carolina recognized the Lumbee Tribe in 1885. In 1956, Public Law 570, the "Lumbee Act," acknowledged the tribe as an "admixture of colonial blood with certain coastal tribes of Indians" but denied it federal services. In the 1990s, the Interior Department rejected the tribe's petition for recognition, saying it could not document cultural, political or genealogical ties to any single historic tribe.

Biden grants clemency to Leonard Peltier

In the last hours of his presidency, President Joe Biden on Sunday commuted the life sentence of Indigenous activist Leonard Peltier, who was convicted in the 1975 killings of two FBI agents. He has served almost 50 years in prison.

During the unrest of the 1970s, Peltier, a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa in North Dakota, joined the American Indian Movement, or AIM, which was dedicated to protecting, preserving and defending treaty rights of tribal Americans. AIM’s reputation was tarnished by acts of violence, most notably the 1972 six-day takeover of the Bureau of Indian Affairs building in Washington.

In 1977, Peltier was convicted of the 1975 murders of two FBI agents during a standoff on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. He was sentenced to two consecutive life sentences.

“He is now 80 years old, suffers from severe health ailments, and has spent the majority of his life (nearly half a century) in prison,” the Biden White House said in a statement. “This commutation will enable Mr. Peltier to spend his remaining days in home confinement but will not pardon him for his underlying crimes.”

A diverse coalition of tribal nations, human rights groups and former law enforcement officials support his release, scheduled for Feb. 18.

The FBI tried to block his release.

“Peltier is a remorseless killer, who brutally murdered two of our own,” former FBI Director Christopher Wray wrote in a letter to Biden on Jan. 10. “Mr. President, I urge you in the strongest terms possible: Do not pardon Leonard Peltier or cut his sentence short.”

Also in 1975, Annie Mae Pictou-Aquash, a Mi'kmaq activist and AIM member from Nova Scotia, Canada, was kidnapped, raped and murdered. A 35-year investigation resulted in convictions of two other AIM members, but her family and supporters believe that Peltier was involved with her killing and expressed disappointment over his release.

Wearable robot teaches endangered Indigenous languages

In the tech world, Native Americans are almost invisible.

Danielle Boyer is looking to change that. The 24-year-old Anishinaabe robotics inventor from the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians in Michigan founded the nonprofit STEAM Connection in 2019 to design, manufacture and donate educational robots to Indigenous students.

Her latest creations, called SkoBots, are wearable animal-shaped robots that help students learn endangered Indigenous languages.

Boyer has distributed 20,000 free robot kits to Indigenous students, advocated for youth in STEM fields and challenged stereotypes about Indigenous peoples' technological capabilities.

Read more:

Native American news roundup, Jan. 5-11, 2025

Tribes laud Biden designation of national monuments in California

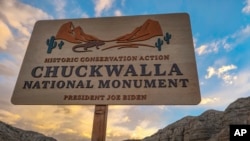

President Joe Biden this week announced plans to designate two new national monuments in California as part of his “America the Beautiful” initiative to conserve at least 30% of U.S. lands and waters by 2030.

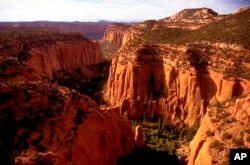

The Chuckwalla National Monument in the southern desert region encompasses about 260,000 hectares (624,000 acres) near Joshua Tree National Park on the ancestral lands of the Iviatim, Nüwü, Pipa Aha Macav, Kwatsáan, and Maara’yam peoples – today, the Cahuilla, Chemehuevi, Mojave, Quechan, and Serrano Nations.

“The area includes village sites, camps, quarries, food processing sites, power places, trails, glyphs, and story and song locations, all of which are evidence of the Cahuilla peoples’ and other Tribes’ close and spiritual relationship to these desert lands," Erica Schenk, Chairwoman of the Cahuilla Band of Indians, said in a statement.

To the north, the Sattitla Highlands National Monument will protect 90,650 hectares (224,000) acres of ancestral lands in Shasta-Trinity, Klamath, and Modoc National Forests near Mount Shasta. This region is sacred to the Pit River Nation and will safeguard critical water resources and rare wildlife species.

In Biden’s final days in office, his administration has issued several environmental protections. On Monday, he banned oil and gas drilling in more than 24 million hectares ( 600 million acres) of coastal waters; on Dec. 26, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland instituted a 20-year ban on mining activities in portions of South Dakota’s Black Hills; and on Dec. 30, his administration announced a 20-year withdrawal of all oil, gas and geothermal development in Nevada’s Ruby Mountain area.

Little interest in Arctic oil and gas leases

The Interior Department announced this week that no bids were submitted for the second oil and gas lease sale in the Coastal Plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

This sale, required by the 2017 Tax Act, aimed to generate $2 billion over 10 years but failed to attract interest. The first sale was held under the Trump administration and also saw little demand, raising only $14.4 million.

All previous leases have been canceled, leaving no active leases in the area.

Interior Department Acting Deputy Secretary Laura Daniel-Davis said the lack of interest shows the Arctic Refuge is too special to risk with drilling.

“The BLM [Bureau of Land Management] has followed the law and held two lease sales that have exposed the false promises made in the Tax Act. The oil and gas industry is sitting on millions of acres of undeveloped leases elsewhere; we’d suggest that’s a prudent place to start, rather than engage further in speculative leasing in one of the most spectacular places in the world.”

Documentary about tribal disenrollment dropped from film festival

Film director Ryan Flynn says he was “elated” in October when his documentary “You’re No Indian” was selected for screening at the 36th annual Palm Springs International Film Festival, which runs through Jan. 13 (see film trailer, above).

The film concerns the growing trend of tribal disenrollment by which some Native American tribes strip individuals and families of their citizenship, making them ineligible for federal benefits and services and, as the documentary stresses, shares in casino revenue.

“When they announced the film schedule, we sold out on the first day,” Flynn said. “And then in mid-December, we got an email saying there had been a scheduling error, and they wouldn’t be able to move forward with our screening.”

Flynn said he was heartbroken.

“I don't mean heartbroken for myself,” he said. “It's for the people whose voices you have been systematically silenced by the powers that be.”

Indigenous rights attorney Gabe Galanda, a citizen of the Round Valley Indian Tribes in California, told VOA that approximately 10,000 tribal citizens from almost 100 tribes have been disenrolled.

VOA reached out to the film festival for comment.

“Due to an unforeseen scheduling error, the festival was unable to proceed with screenings of the film YOU’RE NO INDIAN,” a spokesperson responded via email. “The festival programming team reached out to the filmmaker to explain the situation and offered to reimburse the director for any non-refundable festival travel fees that may have been incurred.”

Federal report shows Native Americans wrongfully billed for health care

Native Americans are twice as likely to have medical debt sent to collections, with average debts that are one-third higher than the national average. This problem is worsened by limited access to year-round health care through the Indian Health Service and inconsistent Medicaid coverage between states, reports the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

The IHS is responsible for providing free health care services in regional clinics. Where specialty services aren’t available, patients may be approved for emergency care outside the program at no cost.

Errors in bill processing and payment delays mean Native individuals are frequently billed for debts they should not owe, the consumer protection bureau says. Improper medical debt can damage individuals’ credit, making them ineligible for jobs, housing, loans and educational opportunities.

The Indian Health Service is responsible for providing free health care services in regional clinics. Where specialty services aren’t available, patients may be approved for emergency care outside the program at no cost.

High winds force Biden to cancel event announcing two new national monuments

Dangerously high winds forced U.S. President Joe Biden to cancel a trip Tuesday to the Eastern Coachella Valley, where he was to announce the creation of two new national monuments in California that will honor Native American tribes.

Winds began gaining strength across Southern California as forecasters warned of "life-threatening, destructive" gusts. The president was in his limousine ready to leave Los Angeles when the event was canceled. The White House initially said Biden would speak in Los Angeles but later announced the event would be rescheduled at the White House next week at a time when others could attend.

The National Weather Service said it could be the strongest Santa Ana windstorm in more than a decade and it will peak in the early hours of Wednesday, when gusts could reach 129 kilometers per hour. Isolated gusts could top 160 kph in mountains and foothills.

Biden's announcement was part of his administration's effort to conserve at least 30% of U.S. lands and waters by 2030 through his "America the Beautiful" initiative. But the cancellation of the trip was also a stark reminder of another administration priority: climate change and the increasing effects of extreme weather.

The proclamations name the Chuckwalla National Monument in Southern California near Joshua Tree National Park and the Sattitla National Monument in Northern California. The declarations bar drilling and mining and other development on the 2,400-square-kilometer Chuckwalla site and roughly 800 square kilometers near the Oregon border in Northern California.

The new monuments protect clean water for communities, honor areas of cultural significance to tribal nations and Indigenous peoples and enhance access to nature, the White House said.

Biden, who has two weeks left in office, announced Monday he will ban new offshore oil and gas drilling in most U.S. coastal waters, including in California and other West Coast states. The plan is intended to block possible efforts by the incoming Trump administration to expand offshore drilling.

The flurry of activity has been in line with the Democratic president's "America the Beautiful" initiative launched in 2021, aimed at honoring tribal heritage, meeting federal goals to conserve 30% of public lands and waters by 2030 and addressing climate change.

The Pit River Tribe has worked to get the federal government to designate the Sattitla National Monument. The area is a spiritual center for the Pit River and Modoc Tribes and encompasses mountain woodlands and meadows that are home to rare flowers and wildlife.

Several Native American tribes and environmental groups began pushing Biden to designate the Chuckwalla National Monument, named after the large desert lizard, in early 2023. The monument would protect public lands south of Joshua Tree National Park, spanning the Coachella Valley region in the west to near the Colorado River.

Advocates say the monument will protect a tribal cultural landscape, ensure access to nature for residents and preserve military history sites.

"The designation of the Chuckwalla and Sattitla National Monuments in California marks an historic step toward protecting lands of profound cultural, ecological and historical significance for all Americans," said Carrie Besnette Hauser, president and CEO of the nonprofit Trust for Public Land.

The new monuments "honor the enduring stewardship of Tribal Nations and the tireless efforts of local communities and conservation advocates who fought to safeguard these irreplaceable landscapes for future generations,'' Hauser said.

Senator Alex Padilla of California called the new monuments a major victory that will safeguard the state's public lands for generations to come.

Designation of the Chuckwalla monument "accelerates our state's crucial efforts to fight the climate crisis, protect our iconic wildlife, preserve sacred tribal sites and promote clean energy," Padilla said. The new Sattitla monument, meanwhile, ensures that land that has "long served as the spiritual center for the Pit River and Modoc Nation" will "endure for generations to come," Padilla said.

The Chuckwalla monument is intended to honor tribal sovereignty by including local tribes as co-stewards, following in the footsteps of a recent wave of monuments such as the Bears Ears National Monument in Utah, which is overseen in conjunction with five tribal nations.

"The protection of the Chuckwalla National Monument brings the Quechan people an overwhelming sense of peace and joy," the Fort Yuma Quechan Tribe said in a statement. "Tribes being reunited as stewards of this landscape is only the beginning of much-needed healing and restoration, and we are eager to fully rebuild our relationship to this place."

In May, the Biden administration expanded two national monuments in California — the San Gabriel Mountains in the south and Berryessa Snow Mountain in the north. In October, Biden designated the Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary along the coast of central California, which will include input from the local Chumash tribes in how the area is preserved.

Last year, the Yurok Tribe in Northern California also became the first Native people to manage tribal land with the National Park Service under a historic memorandum of understanding signed by the tribe, Redwood National and State Parks and the nonprofit Save the Redwoods League, which is conveying the land to the tribe.

Native American news: 2024 in review

The 2024 elections in the U.S. highlighted the growing impact of Native American voters, especially in swing states such as Arizona. Home to 22 tribes, Native voters played a key role in that state’s results.

Unfounded claims of voter fraud and election irregularities four years ago triggered a surge of restrictive voting laws across the United States for this year’s vote, raising concerns about potential harassment and intimidation of voters and poll workers.

Exit polls showed a shift in Native American support toward Republican Donald Trump, driven by economic concerns and alignment with his party’s traditional values.

Biden apologizes for federal boarding school system

During his October visit to the Gila River Indian Community in Arizona, President Joe Biden delivered a long-awaited official apology to Native Americans for the Indian boarding school system that severed the family, tribal and cultural ties of thousands of Indian children over multiple generations.

“I say this with all sincerity: This, to me, is one of the most consequential things I've ever had an opportunity to do in my whole career as president of the United States,” Biden said, calling it his “solemn responsibility.”

In a related story, the Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition in May launched the National Indian Boarding School Digital Archive, a public archive of information on boarding schools and students that includes documents, photographs and other ephemera.

Supreme Court: Feds must pay for tribal health care programs

In a landmark June decision, the Supreme Court ruled that the Indian Health Service (IHS) must fully reimburse tribes for the administrative costs of running their own health care programs.

Chief Justice John Roberts explained that if the federal government’s position had prevailed — opposing payment of administrative costs — it would have created a “systemic funding shortfall” for tribes that chose to manage their own health care programs, thus imposing “a penalty for pursuing self-determination.”

In a dissenting opinion, Justice Brett Kavanaugh argued that the ruling could cost the government as much as $2 billion.

The 1975 Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act allows federally recognized tribes to contract with the Indian Health Service to operate their own health care programs, which IHS would otherwise manage. When a tribe opts for this arrangement, IHS provides the funds it would have used to run those programs.

Museums, institutions, under pressure to return Native remains

The Interior Department issued new regulations in 2024 to improve compliance with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. Passed in 1990, it calls on federally funded museums and other institutions to inventory and return to tribal communities all ancestral remains and funerary objects.

The new rules cut out a loophole that allowed institutions to hang onto “culturally unidentifiable” remains and give tribes a greater say in the process. Throughout the year, institutions have made some progress, but as ABC News reported in November, nearly 500 museums and federal agencies have so far failed to identify or make available for repatriation more than 90,000 remains and associated cultural objects.

South Dakota governor banned from nine Indian reservations

Since taking office in 2019, South Dakota Governor Kristi Noem has had a tense relationship with the nine tribes in her state. Tensions escalated in January when Noem accused Mexican drug cartels of operating on reservations and then later suggested that tribal leaders were “personally benefiting” from that drug trade.

Oglala Lakota tribal president, Frank Star Comes Out, who had earlier declared a state of emergency over drug use and violence on the Pine Ridge Reservation, accused Noem of being politically motivated and in February became the first of nine tribes to ban her from the reservation.

Land Back movement sees some wins

The Land Back movement, a push for the return of lands lost to colonization, grew in momentum in 2024, and several tribes regained control of land or ancestral territories.

Among the successes, the Yurok Tribe of coastal California signed a memorandum of understanding to co-manage with the National Park Service 50 hectares (125 acres) of land they lost after the California gold rush in the mid-19th century.

TheLeech Lake Band of Ojibwe reclaimed more than 4760 hectares (11,000 acres) of ancestral land that the federal government seized from them in the 1940s.

And in the largest ever return of Indigenous land, the nonprofit Trust for Public Land returned 12,545 hectares (31,000 acres) to the Penobscot Tribe in Maine, with no easements or restrictions on its use.

Birth of white buffalo viewed as a blessing and a warning

A rare white buffalo calf was born June 4 in Yellowstone National Park's Lamar Valley, an event of profound cultural and spiritual significance for many Native American tribes.

According to Lakota tradition, White Buffalo Calf Woman appeared to the Lakota people during a time of great need, bringing them the sacred pipe and teachings of harmony, respect and gratitude for the Earth.

The pipe has been passed down for generations and is now held by Chief Arvol Looking Horse from the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, who explains the tradition in the video below:

Looking Horse presided over a ceremony in Yellowstone June 26, naming the calf Wakan Gli, (“Sacred Return”) and warning that the calf’s birth was both a fulfillment of prophecy and a warning for people to unite and protect the earth.

Wounded Knee anniversary renews push to revoke US Medals of Honor

Each year, the Sitanka Wokiksuye, or Chief Big Foot Memorial Ride, remembers the 1890 Wounded Knee massacre with a 14-day journey on horseback from the Cheyenne River Reservation to the site of that violence on South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Reservation.

By the late 1880s, the Native American Lakota tribe was confined to reservations, their traditional ways of life forbidden, and the buffalo, critical to their survival, were decimated. Left to survive on inadequate U.S. government rations, the Lakota and many other tribes found hope in the Ghost Dance, a messianic movement that promised a return to their former way of life.

The U.S. Army interpreted the dance as a call to arms and sent the 7th Cavalry to suppress the dancing and arrest Hunkpapa Lakota leader Sitting Bull, who the U.S. government believed was orchestrating rebellion.

Sitting Bull was shot dead, and his half-brother, Hunkpapa Lakota leader Sitanka, dubbed Big Foot, led his followers to consult with the Oglala leadership on the Pine Ridge Reservation.

The Army intercepted them and forced them to camp at Wounded Knee village; the next day, while confiscating weapons, a shot rang out, triggering the Army to open fire. By the end of the day, Big Foot and about 300 Lakota, including unarmed women, and children, lay dead. The event was celebrated as a victory for the U.S. Army, and the government awarded Medals of Honor to 20 cavalry soldiers for their actions.

This year, the Big Foot riders and their supporters hoped that President Joe Biden might revoke those medals.

Oliver “O.J.” Semans has spent years lobbying U.S. administrations to “take back honor wrongly bestowed.” The Sicangu Lakota voting rights advocate from the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota lost many ancestors in that violence and said, “If Biden’s going to do anything, the best day would be December 29th” as that is the anniversary of the massacre.

Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren introduced the Remove the Stain Act in 2019, calling on the Army to revoke those Medals of Honor. Despite some bipartisan support and backing from Native leaders and advocacy groups, the bill did not advance.

Administrative action

This July, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin ordered a review of medals of honor given for what he called the “engagement” at Wounded Knee to assess whether awardees violated the laws and military ethics of the era.

"It's never too late to do what's right," said an unnamed senior defense official quoted in the Pentagon press release that announced the decision. "And that's what is intended by the review that the secretary directed, which is to ensure that we go back and review each of these medals in a rigorous and individualized manner to understand the actions of the individual in the context of the overall engagement."

Austin directed a review panel of five members – three from the Department of Defense and two from the Interior Department -- to gather all relevant historical records and assess the actions of those soldiers based not on today’s standards but by those at the time.

"This is not a retrospective review," said another unnamed DoD official in the same Pentagon press release. "We're applying the standards at the time. And that's critical because we want to make sure that as these are reviewed and as a recommendation is made to the secretary and then to the president that we have applied the standards appropriately, while ensuring that we look at the context.”

The U.S. Army’s 1863 General Orders No. 100, also known as the “Lieber Code,” banned using excessive force, killing noncombatants, attacking during a ceasefire, and looting.

The Army held two sets of hearings on the matter in early 1891, interviewing officers and witnesses that included newspaper reporters, a surgeon and a Catholic priest.

“The Army was on the cusp of being a modern professional force, and so they at least made an effort to investigate allegations of crimes at Wounded Knee,” said Dwight S. Mears, author of “The Medal of Honor: The Evolution of America's Highest Military Decoration.”

In the end, the Army excused the cavalry’s actions as accidental and unintentional, and the U.S. Secretary of War recommended commendations.

“There was no political will to prosecute anybody, but they did collect a lot of evidence,” Mears said, “and if you sift through that with a critical eye, you can find a whole bunch of places where officers misrepresented themselves, which is a crime under oath.”

Three months after the massacre, the first Medal of Honor for Wounded Knee was awarded to an officer who, according to the medal citation “killed a hostile Indian at close quarters, and although entitled to retirement from service, remained to the close of the campaign.”

An award without guidelines

The U.S. Medal of Honor was created in 1863 to recognize acts of bravery, gallantry, and other distinguished actions in battle.

"But the Army didn't publish any standards for awarding it until 1889, so the commanding general of the Army just gave the medal out however he saw fit,” Mears explains.

In 1916, Congress directed the Army to review more than 2,600 medals and determine whether any had been issued “for any cause other than distinguished conduct by an officer or enlisted man in action involving actual conflict with an enemy.”

After an eight-month review, the Army struck more than 900 medals from the record. All of the Wounded Knee medals remained in place.

This year’s Wounded Knee review panel was given until October 15 to present its findings. By mid-November, Cheyenne River Sioux President Ryman LeBeau reported that the panel had voted three-to-two in favor of maintaining all medals awarded.

Semans believes that review was flawed from the start.

“Military historians weren’t used, and it was done over such a short period of time that evidence really couldn’t be put together,” he said.

Senator Warren and South Dakota Senator Mike Rounds asked the Interior and Defense departments to extend the review’s deadline to give stakeholders — including tribes, survivor descendants and historians a chance to weigh in.

"The devil is in the details,” Mears said. “If you don't know what actually happened at Wounded Knee, you might assume that every member of the 7th Cavalry, you know, just stood up and executed Lakota. And that is not what the record supports.”

To date, neither the Pentagon nor the White House has made any statement about the review panel’s findings.

“We have no additional updates to share at this time,” a Defense Department official told VOA.

What is the Native American Church and why is peyote sacred to members?

The Native American Church is considered the most widespread religious movement among the Indigenous people of North America. It holds sacred the peyote cactus, which grows naturally only in some parts of southern Texas and northern Mexico. Peyote has been used spiritually in ceremonies, and as a medicine by Native American people for millennia.

It contains several psychoactive compounds, primarily mescaline, which is a hallucinogen. Different tribes of peyote people have their own name for the cactus. While it is still a controlled substance, U.S. laws passed in 1978 and 1994 allow Native Americans to use, harvest and transport peyote. However, these laws only allow federally recognized Native American tribes to use the substance and don't apply to the broader group of Indigenous people in the United States.

The Native American Church developed into a distinct way of life around 1885 among the Kiowa and Comanche of Oklahoma. After 1891, it began to spread as far north as Canada. Now, more than 50 tribes and 400,000 people practice it. In general, the peyotist doctrine espouses belief in one supreme God who deals with humans through various spirits that then carry prayers to God. In many tribes, the peyote plant itself is a deity, personified as Peyote Spirit.

Why was the Native American Church incorporated?

The Native American Church is not one unified entity like, say, the Catholic Church. It contains a diversity of tribes, beliefs and practices. Peyote is what unifies them. After peyote was banned by U.S. government agents in 1888 and later by 15 states, Native American tribes began incorporating as individual Native American Churches in 1918.

In order to preserve the peyote ceremony, the federal and state governments encouraged Native American people to organize as a church, said Darrell Red Cloud, the great-great grandson of Chief Red Cloud of the Lakota Nation and vice president of the Native American Church of North America.

In the following decades, the religion grew significantly, with several churches bringing Jesus Christ's name and image into the church so their congregations and worship would be accepted, said Steve Moore, who is non-Native and was formerly a staff attorney at the Native American Rights Fund.

"Local religious leaders in communities would see the image of Jesus, a Bible or cross on the wall of the meeting house or tipi and they would hear references to Jesus in the prayers or songs," he said. "That probably helped persuade the authorities that the Native people were in the process of transformation to Christianity."

This persecution of peyote people continued even after the formation of the Native American Church, said Frank Dayish Jr. a former Navajo Nation vice president and chairperson for the Council of the Peyote Way of Life Coalition.

In the 1960s, there were laws prohibiting peyote in the Navajo Nation, he said. Dayish remembers a time during that period when police confiscated peyote from his church, poured gasoline on the plants and set them on fire.

"I remember my dad and other relatives went over and saved the green peyote that didn't burn," he said, adding that it took decades of lobbying until an amendment to the American Indian Religious Freedom Act in 1994 permitted members of federally recognized Native American tribes to use peyote for religious purposes.

How is peyote used in the Native American Church?

Peyote is the central part of a ceremony that takes place in a tipi around a crescent-shaped earthen altar mound and a sacred fire. The ceremony typically lasts all night and includes prayer, singing, the sacramental eating of peyote, water rites and spiritual contemplation.

Morgan Tosee, a member of the Comanche Nation who leads ceremonies within the Comanche Native American Church, said peyote is utilized in the context of prayer — not smoked — as many tend to imagine.

"When we use it, we either eat it dry or grind it up," he said. "Sometimes, we make tea out of it. But, we don't drink it like regular tea. You pray with it and take little sips, like you would take medicine."

Tosee echoes the belief that pervades the church: "If you take care of the peyote, it will take care of you."

"And if you believe in it, it will heal you," he said, adding that he has seen the medicine work, healing people with various ailments.

People treat the trip to harvest peyote as a pilgrimage, said Red Cloud. Typically, prayers and ceremonies take place before the pilgrimage to seek blessings for a good journey. Once they get to the peyote gardens, they would touch the ground and thank the Creator before harvesting the medicine. The partaking of peyote is also accompanied by prayer and ceremony. The mescaline in the peyote plant is viewed as God's spirit, Red Cloud said.

"Once we eat it, the sacredness of the medicine is inside of us and it opens the spiritual eye," he said. "From there, we start to see where the medicine is growing. It shows itself to us. Once we complete the harvest, we bring it back home and have another ceremony to the medicine and give thanks to the Creator."

Native American tribe closer to acquiring more land in Arizona after decades of delay

Federal officials have joined with the state of Arizona to begin fulfilling a settlement agreement that was reached with the Hopi Tribe nearly three decades ago, marking what tribal officials described as a historic day.

Government attorneys filed condemnation documents on Friday to transfer dozens of square kilometers of state land into trust for the Hopi. The tribe will compensate the state nearly $4 million for more than 80 square kilometers of land near Winslow.

It could mark the first of more transfers of land into trust to help eliminate the checkerboard of ownership that characterizes much of the lands used by the tribe for ranching in northeastern Arizona.

A long time coming

Friday's filing was born out of the 1996 passage of the Navajo-Hopi Land Dispute Settlement Act, which ratified an agreement between the Hopi and federal government that set conditions for taking land into trust for the tribe.

The wrangling over land in northeastern Arizona has been bitter, pitting the Hopi and the Navajo Nation against one another for generations. The federal government failed in its attempt to have the tribes share land and after years of escalating conflict, Congress in 1974 divided the area and ordered tribal members to leave each other's reservations.

The resulting borders meant the Navajo Nation — the country's largest reservation at close to 70,000 square kilometers — surrounded the nearly 6,500-square-kilometer Hopi reservation.

Since the 1996 settlement, the Hopi Tribe has purchased private land and sought to take neighboring state lands into trust in hopes of consolidating property for the tribe's benefit.

A historic day

There have been many roadblocks along the way, including in 2018 when the tribe sought the support of local governments in northern Arizona to back a proposed transfer for land south of the busy Interstate 40 corridor. Those efforts were stymied by the inclusion of national forest tracts in the Flagstaff area.

Hopi Chairman Tim Nuvangyaoma said in a statement Friday that he was grateful for everyone who worked to make the condemnation filing a reality and that the timing for this historic moment was fitting.

"Within Hopi, it is our time of the soyal'ang ceremony — the start of the New Year and the revitalization of life," he said.

Gov. Katie Hobbs, who first visited the Hopi reservation in 2023, acknowledged that the tribe has been fighting for its rights for decades and that politicians of the past had refused to hear the voices of tribal communities.

"Every Arizonan should have an opportunity to thrive and a space to call home, and this agreement takes us one step closer to making those Arizona values a reality," she said Friday.

More transfers and economic opportunities

In November, the Navajo Nation signed a warranty deed to take into trust a parcel of land near Flagstaff as part of the federal government's outstanding obligations to support members of that tribe who were forcibly relocated as a result of the Navajo-Hopi dispute.

Navajo leaders are considering building a casino on the newly acquired land, saying such a project would provide significant economic benefits.

For the Hopi, bringing more land into trust also holds the promise of more economic opportunities. The state lands near Winslow that are part of the condemnation filing are interspersed with Hopi-owned lands and have long been leased to the tribe for ranching and agricultural purposes, according to the U.S. Justice Department.

Federal officials said Friday's filing is the first of an anticipated series of condemnation actions that ultimately would result in the transfer of more than 1440 square kilometers of state land into trust for the Hopi Tribe.

Media report: More than 3,100 Native American children died in US boarding schools