As drug-resistant infections become an increasingly serious threat worldwide, new research show the problem may be spreading right under our feet.

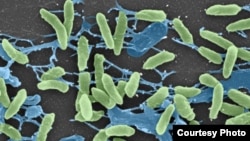

A new study in the journal Science shows that disease-causing germs and harmless bacteria in the soil are exchanging genes that make them resistant to antibiotics — a finding that may have implications for the widespread use of antibiotics in livestock.

Antibiotic resistance among pathogenic bacteria — the kind that make people sick — is one of the most serious problems in medicine today.

“It’s scary the number of pathogens now for which there are either very few or no drugs available to treat them,” says Gautam Dantas, study co-author and Washington University immunologist.

Swapping genes

The bacteria that cause tuberculosis, skin infections, food poisoning and other diseases become resistant to antibiotics either through mutations in their genetic material or by swapping genes with other bacteria.

According to Dontas, even completely different species can swap gene-carrying DNA.

“Bacteria as different as, say, you and I are to a plant, are still able to exchange DNA,” he says.

Identical genes

While researchers have long known that dirt is teeming with both harmless and deadly bacteria ready to exchange genes, they didn't know for sure what was happening.

But after analyzing 11 different soil samples, Dontas and his colleagues found about 100 different antibiotic resistance genes.

“Out of those 100 or so genes, seven of them had exactly the same DNA sequence as antibiotic-resistance genes that have been found in a whole bunch of pretty deadly pathogens from around the world," says Dontas, explaining that they cannot yet tell whether the genes came from the pathogens first and jumped to the soil bacteria or vice versa.

“But I think either scenario is plausible and either scenario, as far as we’re concerned, is scary,” he adds.

Food animals

Dontas says doctors know that over-using antibiotics for patients is helping to increase antibiotic resistance.

“What this work says is that we need to now also consider what happens when we dump antibiotics into food animals,” he says.

On many farms worldwide, antibiotics are routinely given to cows, pigs and chickens to prevent disease and help them grow. According to some figures, more antibiotics are used for healthy animals than for sick people, and the drugs often end up in the soil through the animals’ manure. Dontas says the new study shows soil has the potential to spawn or harbor resistance that can jump to human pathogens.

“This is not a distinct habitat," he says. "These transfers can occur, so practices in one environment are going to impact the other environment.”

Limited risk

The Animal Health Institute, which represents livestock drug makers, says antibiotics break down quickly in manure and in soil, and that regulators consider that risk before they approve the drugs. The industry group also notes that antibiotic resistance occurs naturally, so assessing whether its use in livestock has any additional impact would require further study.

While drug makers support regulatory efforts to eliminate the role of antibiotics in the growth of healthy animals, industry-wide eradication of antibiotics, they say, would have worse implications for public health, as it would only increase the number of sick animals in the food supply.

A new study in the journal Science shows that disease-causing germs and harmless bacteria in the soil are exchanging genes that make them resistant to antibiotics — a finding that may have implications for the widespread use of antibiotics in livestock.

Antibiotic resistance among pathogenic bacteria — the kind that make people sick — is one of the most serious problems in medicine today.

“It’s scary the number of pathogens now for which there are either very few or no drugs available to treat them,” says Gautam Dantas, study co-author and Washington University immunologist.

Swapping genes

The bacteria that cause tuberculosis, skin infections, food poisoning and other diseases become resistant to antibiotics either through mutations in their genetic material or by swapping genes with other bacteria.

According to Dontas, even completely different species can swap gene-carrying DNA.

“Bacteria as different as, say, you and I are to a plant, are still able to exchange DNA,” he says.

Identical genes

While researchers have long known that dirt is teeming with both harmless and deadly bacteria ready to exchange genes, they didn't know for sure what was happening.

But after analyzing 11 different soil samples, Dontas and his colleagues found about 100 different antibiotic resistance genes.

“Out of those 100 or so genes, seven of them had exactly the same DNA sequence as antibiotic-resistance genes that have been found in a whole bunch of pretty deadly pathogens from around the world," says Dontas, explaining that they cannot yet tell whether the genes came from the pathogens first and jumped to the soil bacteria or vice versa.

“But I think either scenario is plausible and either scenario, as far as we’re concerned, is scary,” he adds.

Food animals

Dontas says doctors know that over-using antibiotics for patients is helping to increase antibiotic resistance.

“What this work says is that we need to now also consider what happens when we dump antibiotics into food animals,” he says.

On many farms worldwide, antibiotics are routinely given to cows, pigs and chickens to prevent disease and help them grow. According to some figures, more antibiotics are used for healthy animals than for sick people, and the drugs often end up in the soil through the animals’ manure. Dontas says the new study shows soil has the potential to spawn or harbor resistance that can jump to human pathogens.

“This is not a distinct habitat," he says. "These transfers can occur, so practices in one environment are going to impact the other environment.”

Limited risk

The Animal Health Institute, which represents livestock drug makers, says antibiotics break down quickly in manure and in soil, and that regulators consider that risk before they approve the drugs. The industry group also notes that antibiotic resistance occurs naturally, so assessing whether its use in livestock has any additional impact would require further study.

While drug makers support regulatory efforts to eliminate the role of antibiotics in the growth of healthy animals, industry-wide eradication of antibiotics, they say, would have worse implications for public health, as it would only increase the number of sick animals in the food supply.