As I watched from the roof of my apartment building in Istanbul, the explosions and gunfire from the Bosphorous bridge got louder and more frequent.

Two blocks from my apartment building, soldiers had opened fire on flag-waving crowds in popular Taksim Square. At 11 p.m., Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan appeared on television, telling the country that a kalkışma girişimi (an uprising attempt) had begun.

A military coup, or power grab, was not unusual in Turkey. Most Turkish people are familiar with the realities of coups, having lived through them in 1960, 1971, 1980 and 1997.

But this one seemed different.

It is nearly impossible to describe the not knowing of who was shooting whom, who was in control of the government, or whose F-16s were flying overhead, except that it was terrifying.

The SIM card on my roommate’s cellphone had been blocked. Twitter and Facebook were throttled to a crawl. For the second time since I arrived in Istanbul, I reassured my family that I was safe by posting a message to Facebook.

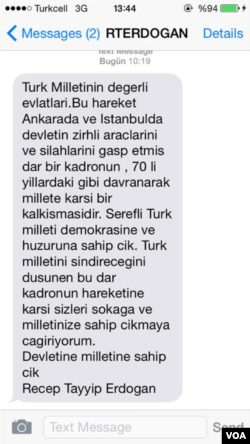

The call to prayer sounded continuously, beckoning Turks to the streets throughout the night, a tactic that has not been used since the Ottoman times. Later, the Turkish government and President Erdoğan would text every phone in the country -- including mine -- calling everyone to the street to “take back the nation” and stop the rebellious military.

President Erdoğan’s text.

By midnight, the sounds of helicopters and F-16s above our ground floor apartment made the coup all too real. I grabbed my camera, went to the roof, and shot video. But as attack helicopters flew into Taksim Square, I headed downstairs.

I was back in my room as the rebels’ F-16s sonically bombed our neighborhood, attempting to enforce a planned curfew. The sonic bombs knocked me down, sucking the air out of my lungs, and broke windows every time an F-16 passed over us.

My Turkish roommate, who had work in the morning, had brushed off news of the coup and gone to bed earlier, but was awokened when a shockwave smashed the front door.

I placed my hand on a window during one sonic boom and felt it move like a liquid.

At the time we had no way of knowing who these airstrikes were targeting. We could only sit in the middle of our living room, away from the windows, and wait. Outside, a trickle of people fled by foot with bags and backpacks, running over the shattered glass that covered the street. As the sonic booms persisted, groups of people in Taksim increased.

But as night passed into morning, the soldiers had stepped down from areas they had controlled in Istanbul. Across the country, more than 245 people had been killed and 1,800 injured.

I finally slept around 7:30 a.m., when it looked unlikely the coup would succeed. The AKP government -- Erdogan’s government -- has steadily eroded the military’s ability to influence politics over the past 14 years, and this coup attempt looked more like an act of desperation than a display of power.

Erdoğan blamed the Gülenist Movement and called for democracy to be defended using the same guerrilla media tactics he often uses to block opponents of his government.

The Gülen Movement (or Hizmet, Cemaat) is a socially minded Sunni Islamist movement that follows the teachings of Fethullah Gülen, a former Erdoğan ally who lives in Pennsylvania in self-imposed exile.

Gülen’s network of supporters runs schools, businesses and newspapers in Turkey and across the U.S. and Muslim world. Since 2013, when Gülenists leaked tapes of top AKP officials linking them to corruption, the government has arrested thousands of suspected Gülenists for plotting to overthrow the government.

Demonstrators have burned effigies of Fethullah Gulen, organized convoys of honking cars and motorcycles, and have continued gathering by the thousands every night since the coup attempt.

***

Conspiracy theories about who is responsible for the botched coup have continued, with most official media running the same headlines: “Democracy Won” and “The People Defeated the Coup.”

As many commentators have pointed out, the city just wants to return to normal. People returned to work over the weekend. Public transport was free.

I am constantly reminded that I am only a guest in this country, that this is not my reality. I will never know how unfair it feels to be confronted with the instability and painful loss that this and terror attacks have caused this year.

I have never once been disrespected or treated with anything less than kindness during my time here. I feel for the Turkish people who have lost loved ones, who have had relatives imprisoned, and whose loyalty is being called into question by the government.

Noah Ringler is studying in Istanbul on the ARIT-BU Fellowship from the U.S. Department of Education, taking four hours of language classes a day at Boğaziçi University to build his Turkish fluency to a professional skill by summer’s end. He attends American University in Washington, D.C.

Two blocks from my apartment building, soldiers had opened fire on flag-waving crowds in popular Taksim Square. At 11 p.m., Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan appeared on television, telling the country that a kalkışma girişimi (an uprising attempt) had begun.

A military coup, or power grab, was not unusual in Turkey. Most Turkish people are familiar with the realities of coups, having lived through them in 1960, 1971, 1980 and 1997.

But this one seemed different.

It is nearly impossible to describe the not knowing of who was shooting whom, who was in control of the government, or whose F-16s were flying overhead, except that it was terrifying.

The SIM card on my roommate’s cellphone had been blocked. Twitter and Facebook were throttled to a crawl. For the second time since I arrived in Istanbul, I reassured my family that I was safe by posting a message to Facebook.

The call to prayer sounded continuously, beckoning Turks to the streets throughout the night, a tactic that has not been used since the Ottoman times. Later, the Turkish government and President Erdoğan would text every phone in the country -- including mine -- calling everyone to the street to “take back the nation” and stop the rebellious military.

President Erdoğan’s text.

By midnight, the sounds of helicopters and F-16s above our ground floor apartment made the coup all too real. I grabbed my camera, went to the roof, and shot video. But as attack helicopters flew into Taksim Square, I headed downstairs.

I was back in my room as the rebels’ F-16s sonically bombed our neighborhood, attempting to enforce a planned curfew. The sonic bombs knocked me down, sucking the air out of my lungs, and broke windows every time an F-16 passed over us.

My Turkish roommate, who had work in the morning, had brushed off news of the coup and gone to bed earlier, but was awokened when a shockwave smashed the front door.

I placed my hand on a window during one sonic boom and felt it move like a liquid.

At the time we had no way of knowing who these airstrikes were targeting. We could only sit in the middle of our living room, away from the windows, and wait. Outside, a trickle of people fled by foot with bags and backpacks, running over the shattered glass that covered the street. As the sonic booms persisted, groups of people in Taksim increased.

But as night passed into morning, the soldiers had stepped down from areas they had controlled in Istanbul. Across the country, more than 245 people had been killed and 1,800 injured.

I finally slept around 7:30 a.m., when it looked unlikely the coup would succeed. The AKP government -- Erdogan’s government -- has steadily eroded the military’s ability to influence politics over the past 14 years, and this coup attempt looked more like an act of desperation than a display of power.

Erdoğan blamed the Gülenist Movement and called for democracy to be defended using the same guerrilla media tactics he often uses to block opponents of his government.

The Gülen Movement (or Hizmet, Cemaat) is a socially minded Sunni Islamist movement that follows the teachings of Fethullah Gülen, a former Erdoğan ally who lives in Pennsylvania in self-imposed exile.

Gülen’s network of supporters runs schools, businesses and newspapers in Turkey and across the U.S. and Muslim world. Since 2013, when Gülenists leaked tapes of top AKP officials linking them to corruption, the government has arrested thousands of suspected Gülenists for plotting to overthrow the government.

Demonstrators have burned effigies of Fethullah Gulen, organized convoys of honking cars and motorcycles, and have continued gathering by the thousands every night since the coup attempt.

***

Conspiracy theories about who is responsible for the botched coup have continued, with most official media running the same headlines: “Democracy Won” and “The People Defeated the Coup.”

As many commentators have pointed out, the city just wants to return to normal. People returned to work over the weekend. Public transport was free.

I am constantly reminded that I am only a guest in this country, that this is not my reality. I will never know how unfair it feels to be confronted with the instability and painful loss that this and terror attacks have caused this year.

I have never once been disrespected or treated with anything less than kindness during my time here. I feel for the Turkish people who have lost loved ones, who have had relatives imprisoned, and whose loyalty is being called into question by the government.

Noah Ringler is studying in Istanbul on the ARIT-BU Fellowship from the U.S. Department of Education, taking four hours of language classes a day at Boğaziçi University to build his Turkish fluency to a professional skill by summer’s end. He attends American University in Washington, D.C.