A box of newly uncovered documents about pioneer Chinese immigrants in the West tells a tale of emptied graves and unfulfilled yearning for home.

Inside is a jumble of yellowed and crinkly paper. Still legible are names, dates and places. The names belong to dead Chinese immigrant workers. Most passed away early in the last century.

Vanished graves

The document trail leads to what once was a Chinese cemetery in John Day, Oregon.

Laundrymen, miners and domestic workers were interred here.

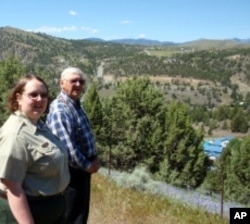

"We don't know who most of the Chinese were who were out here," says Christina Sweet, Oregon State Parks curator. "They're pretty lost to history."

Sweet works at the Kam Wah Chung historic site in John Day. The unique state park highlights the fact that a century ago, Chinatowns sprung up all over the American West. She estimates there were up to 1,500 residents at the height, around 1880.

Chinatowns rose around mining boomtowns, like John Day, as well as at coastal fish canneries. But now, the traces have faded away. A few houses, a shed and a driveway sit where the town's small Chinese cemetery once was.

"Nothing is here," Sweet says. "It's all developed into houses and roads. The landscape is changed. The gravesites aren't here. They kind of get lost to history and to people's memory, which makes these records pretty exciting."

The records also lead to Baker City, Oregon.

The Chinese cemetery there, while a bit overgrown, is preserved. But there are rows of depressions in the ground where 62 years ago, just about all of the remaining Chinese immigrants buried here were dug up. Their remains were sent back to China to be reburied where their families could visit the graves, and their spirits could protect the living.

Good karma

All over the West, Chinese Benevolent Societies systematically dug up remains and sent them home for reburial.

The newly recovered documents detail two of those campaigns in Oregon. In 1928, 615 remains made the journey home. Then again, after World War II, another 559 were collected.

In Portland, Rebecca Liu found records of the fundraising campaign for that second effort. "It's a request sent out to every city, every Chinese community in Oregon," she says. "So everybody [contributes] a dollar, $5, $10, $3. They are all willing to chip in, particularly the businesses."

The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association organized the effort. Liu teaches Chinese language classes for that group, which still exists today. Their 1949 shipment would be the last large-scale exhumation of this type in the Northwest.

"Sending somebody's remains back home, we consider it is a good deed," Liu explains. "You carry it as good karma. That's what the American people say, karma."

Unfortunately, somewhere along the way, the enterprise must have picked up some bad karma, too. Legal records include a case of the wrong body being dug up. Also, a shipping agent was accused of embezzling what was supposed to be the cargo payment to deliver the bones from Portland to Hong Kong.

But the biggest problem was that in mid-1949, China was sinking into the throes of civil war.

Left in limbo

So whatever happened to that final shipment of bones?

Ivy Lin wondered the same thing. Last year, the documentary filmmaker flew to Hong Kong to see if she could pick up the trail of the pioneer immigrants. Her quest turned into a movie titled, "Come Together Home."

The carefully crated boxes of bones were addressed to a charity hospital in Hong Kong. The box of historic documents includes a receipt letter proving it got there.

But then, Lin says, the Northwest immigrants' bones were marooned. "By the time they arrived in Hong Kong, the civil war already started in China. So the Communist Party in China closed the borders."

China would remain a closed country for decades. That caused overseas Chinese to pretty much stop the practice of exhuming immigrant graves and sending the remains home. Lin says the wandering souls shipped from Oregon in 1949 are still warehoused in Hong Kong. "They just left home for so long that a lot of them I believe they lost contact with them."

Historical treasure box

That's where the document trail ends, but there is one more twist.

Several academics have detected a reversal in the flow of bones across the Pacific, as in the case of Ivy Lin, whose father passed away in Taipei 10 years ago. "We have talked about moving my dad's ashes over to the U.S. because I don't really see myself going back to Taiwan."

Lin is among several history buffs who called the historical records a "treasure box." The documents will be placed in an archive in Oregon to make them available for further study.