The battle to succeed the nation's first black president arrives Tuesday in Farmville, Virginia, one of the towns where the modern civil rights movement began.

A student strike here Farmville, Virginia in 1951 helped bring an end to racial segregation in public education.

The vice presidential debate at Farmville's Longwood University takes place as racial tensions are in the headlines over a string of police shootings of unarmed black men.

Many in Farmville hope to use the town's turbulent history as a source of strength to cope with the present strains.

It won't be easy. The hurt runs deep.

The people's vote

Farmville's Main Street -- and there is really only one main street in the tiny town -- runs past the classic tiny diner, the barber shop, a string of antiques stores, and a courthouse that belongs in a Norman Rockwell painting.

Commonwealth's Attorney Megan Clark's office is in that picture-postcard courthouse. She is the first African American chief prosecutor in Prince Edward County, where Farmville is the county seat.

But she says she never ran on her race.

"Some people would go into the dialogue with me of, 'Oh, are you trying to get the black vote?' I'm like, 'Nope, I'm trying to get the people's vote,'" Clark says. "I'm not going to go down that path."

Some comments were more hurtful. She says she was told there were enough people of color in elected positions and she should wait her turn.

Those remarks are the echoes of segregationist rhetoric that Rev. J. Samuel Williams, Jr. lived with daily, growing up in segregated Virginia in the 1940s and '50s. But it was his high school class that began to change the conversation.

Williams was president of the class of 1952 at blacks-only Robert Russa Moton High School. The school was built for 180 students. When Williams attended, there were more than 400. Some classes were taught in tarpaper shacks that were cold in the winter and hot in the summer.

Whites-only Farmville High School had a gymnasium, a cafeteria, a teachers lounge. Moton had none of them. The textbooks Moton students used were hand-me-downs from the white school, often with missing pages and racial slurs written in them.

Even Moton's football equipment was secondhand. "When uniforms came to us, that meant the white high school had just gotten [new] uniforms." His team would "go through a pile and pick out a number," Williams says.

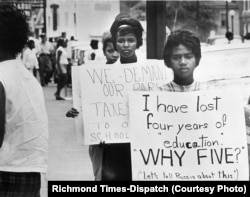

In 1951, Williams joined a group of students who led a strike to demand a new school. Three years later, they had won much more.

‘Not right now’

Their protest went all the way to the Supreme Court. It was one of five cases combined in Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark 1954 decision that ended school segregation.

The court ruled that schools must be integrated. But it didn't say when. All it said was, "with all deliberate speed."

"That meant take your time," Williams says. "That meant not right now."

Rather than integrate, Prince Edward County closed its entire public school system.

A private school for well-off whites opened in Farmville when the public schools closed. But most blacks and poor whites went without an education for five years before the courts stepped in again and integrated the public schools.

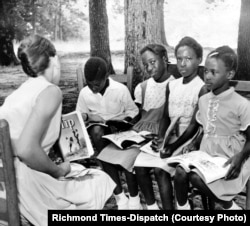

Theresa Clark was 6 years old when the schools closed. Every day, her mother drove her to a neighboring county. But other counties started enforcing residency requirements.

Clark's second-grade teacher checked on her students. When Clark gave her teacher her address in Prince Edward County, her teacher told her, "'If that's your address then you don't belong here,'" she says. "'You go home and you ask your mother what your address is.'"

Her mother was livid. She made Clark memorize a false address.

She scowls, remembering. "At that moment, my mother taught me to lie," she says. "I had to for survival."

TV cameras covered the reopening of Farmville's schools in 1964. "There was one white student who was being interviewed," Clark says. "I remember thinking, why aren't we being interviewed?"

The payoff

She is now chair of the Longwood University department of social work. When Clark and her husband had daughters of her own, education was paramount.

"We were on every committee there was," she says. "Some of the teachers would ask us, 'Why are you here? She has an A.' We want to talk about the A. How did she get it? What did she do?"

It paid off. One of those daughters is Megan Clark.

Rev. Williams said a prayer at Megan's swearing-in as chief prosecutor.

Megan says that's when the significance of the moment hit her.

"He is a very stoic man. He is a very strong man. And he had tears in his eyes about what he was able to witness, in this particular county."

But, she adds, there is still a long way to go. And the recent string of shootings of unarmed black men has been a setback.

"It's like you have a scab that's healing, and it's now festering again."

She doesn't want to see something similar happening in Prince Edward County. So this August, she held a public forum on community policing. Officers and community members talked about the issues the shootings have raised nationwide: racial profiling, implicit bias, body cameras and more.

Others are following her lead. Hakeem Croom, assistant dean at nearby Hampden-Sydney College, and Longwood University alumna Karima ElMadany, say they were inspired by Megan to keep the conversation going with a "peace walk" and forum of their own. More than 100 police and community members took part.

Both Croom and ElMadany have their own stories of modern-day discrimination. ElMadany says once, when she and her friends were detained without cause, the police told her that if they had been white the officer would have let them go. Croom, from New York City, says he's been stopped and frisked many times.

"I've had an officer tell me I looked like I sold drugs," he says. "I don't know what that looks like."

Hurt and healing

But they see Farmville's history as a source of strength for change. Moton High School is now a museum and civil rights teaching center. The town hosts a walking tour of the significant sites in the movement, including First Baptist Church, where Martin Luther King, Jr. visited in 1962 during the school closings.

Moton Museum and Longwood University are publishing the stories of people affected by the struggle for civil rights in education. That's helping some to heal, Theresa Clark says.

For others, however, "It's unimaginable the types of hurt feelings that still exist," she adds. "And individuals can't get over it."

Rev. Williams sees positive changes in race relations in the county. "But there's still a lot of reluctance in education," he adds. Prince Edward County's majority-minority public schools still struggle with underfunding and underperformance. "There's still a lot of reluctance in law enforcement and politics."

And in this election, when Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump says he will "make America great again," Williams says, "They're saying that because something has been done for blacks....'We've got to get it back to the days of segregation and discrimination.' That's what they're talking about."

When Barack Obama was elected as the first African American president, pundits wondered whether America had become a "post-racial" society. But Theresa Clark says the tensions that have surfaced as Obama's term winds down shows how foolish that idea was.

"How could you think, just because our president is African American that all divisions were healed?" she says.

"Until we can be done with firsts, I think that we will still be climbing," her daughter adds.